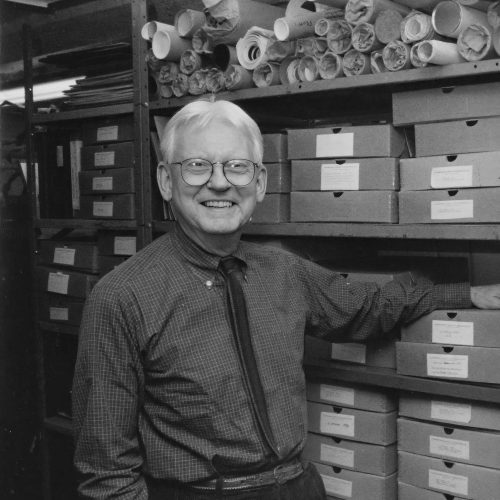

Peter Wright

A man of the theatre through and through, in this conversation Peter Wright shows us that fulfilling one’s destiny can be fraught with difficulties and that the path is not always clear-cut. He talks about seeing his first ballet, running away from school and then joining Kurt Jooss’ company, Ballet Jooss, as an apprentice in 1943. He tells us about the other companies he danced for before the moment, in 1949, when he first joined Sadler’s Wells Theatre Ballet.

This episode is introduced by Darcey Bussell.

First published: July 29, 2025

Biography

Peter Wright was born in London in 1926. He was originally a pupil of Kurt Jooss, the German dancer and choreographer whose work combined Expressionist modern dance movements with classical ballet. He later studied with more purely classical ballet teachers, such as Vera Volkova and Peggy van Praagh.

He experienced the workings and aesthetic of many varied companies and built up a rare knowledge of effective productions, theatrically and technically. Peter joined the Ballet Jooss for a year in 1945, Metropolitan Ballet in 1947 and St James’ Ballet in 1948. He was a soloist with Sadler’s Wells Theatre Ballet from 1949-51, before returning to Ballet Jooss for one more year.

In 1952 he returned to Sadler’s Wells Theatre Ballet, becoming assistant ballet master there in 1955. This was followed by two years of teaching at the Royal Ballet School, at Barons’ Court in London. After assisting Peggy van Praagh at the Edinburgh Festival in the summer of 1958 he went to Stuttgart Ballet in Germany as assistant ballet master. It was here that Peter began to hone his production skills. He produced and directed Giselle for Stuttgart, Cologne and for the Royal Ballet Touring Company. Many subsequent productions particularly Giselle, The Sleeping Beauty, The Nutcracker and Coppélia were to follow, for ballet companies all over the world. He also choreographed for The Royal Ballet and Western Theatre Ballet.

Direction and production were to be his forte and after enterprising work for BBC TV in the 1960s, he re-joined The Royal Ballet as Associate Director in 1970. By 1974 he was Artistic Director of Sadler’s Wells Royal Ballet and in 1990 he was the inspiration and instigator of this company’s move to Birmingham to become The Birmingham Royal Ballet.

Peter Wright has been the recipient of many honours and awards, including a CBE in 1985, a KBE in 1993 and on his retirement in 1999, Director Laureate of Birmingham Royal Ballet. In 2016, he published his autobiography Wrights and Wrongs: My Life in Dance.

Transcript

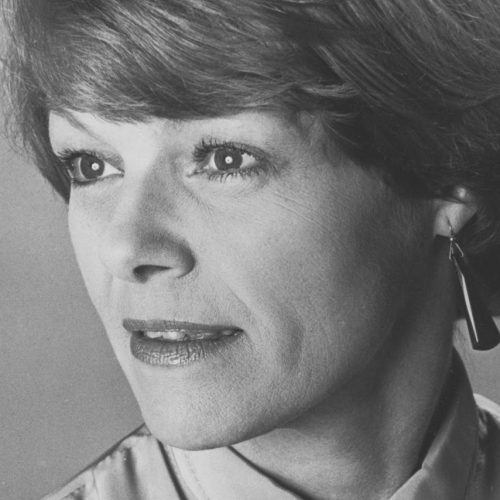

in conversation with Natalie Steed

Peter Wright: I came into dance, should we say, too late. I was already pushing seventeen and it was all an amazing adventure. I suddenly got a passion to dance I didn’t know what sort of kind of dancing it was. It wasn’t necessarily the ballet. I just wanted to prance about the place. And I found, in the little shows we were doing, that sometimes I was actually doing choreography and I didn’t even know what choreography was.

Anyway, in the school holidays, my mother took me to see a ballet. It was The International Ballet. The curtain went up and there was this vision of Les Sylphides with these lovely ladies, in their white costumes, blue lights and this poet standing in the middle. They started to move and everything and I was absolutely enraptured and I turned to my Mother as the curtain went down and said, “That’s for me!”

And that’s how it all began actually. Disastrously, because afterwards, we went home and my mother told my father who was quite a strict Quaker that I had this passion to dance and I said to her, “I’ve obviously got to start at once. I can’t stay on at school any more. I’ve got start now!”

Anyway, my father took a very different view to that and was shocked and I got sent straight back to Bedales, quick, before anything. And I was sort of saying, “I’ve got to train.”

Well, back at school I didn’t get on very well and my father gave instruction to, in no circumstance was I to be in touch with any of these “ballet people” or anything like that. I got angrier and angrier and another friend of mine, we decided we would run away from this lovely school. We ran away down to Somerset, hitchhiking, in February of all months. And it was a disaster because it was freezing cold. All our ideas were that she was going to do lightning sketches, because she could draw beautifully, I was going to dance around the place and pass the hat round. But it was so cold there was no one anywhere anyway. We managed to survive for two nights in an old cow field and then turned ourselves in to the police and were shipped back to home.

Anyway, it convinced my father that, “He obviously wants to do that”, but he told me I had to go back to school and take my school certificate. Then he would let me do it but he wouldn’t give me any money. I’ve got to make my own way.

At this time the war was still on 1943. In the end I managed to get myself a job as an apprentice with a company called the Ballet Joos from Germany. It wasn’t a classical ballet company. They concentrated more on dance drama. Joos had revolted against classical ballet, as he knew it, in Germany, in all the opera houses. He found this rather wonderful way of expressive movement. He had created this famous ballet called The Green Table, an anti-war ballet: very dramatic and very powerful. It caused a sensation in Paris when there was a big choreographic competition. They won the competition and quite a lot of money and with that money he started this group, this was in the early 30s, just when Hitler was coming into power. They escaped to England and set up, here in England, under the auspices of Dorothy Elmhirst down in Totnes, in Devon. Dartington it was. If they hadn’t they would all have been arrested, especially the Jewish people. Joos wasn’t Jewish himself.

Then of course, war came and most of them were shipped off to camps and things. Even Joos himself, he was shipped, he got shipped to South America at one point. Great struggle. And finally though before the war had ended Joos had got himself back to England and managed to gather together the dancers. This was 1943. Which just coincided when I wanted to get going

Natalie Steed: How did you persuade him to take you?

Peter Wright: Funnily enough, it wasn’t difficult. First of all, I went to see Ninette de Valois, with my father. He was enchanted with de Valois but he wasn’t enchanted with the ballet, of course.

I had, funnily enough, hurt my back very badly before I was going to go and see her. We sat in his office for two hours no sign of Ninette de Valois. Finally she appeared rushing in and I was sitting on the chair, there was only one chair. She saw my father made a bee line for him, said, “I’m so sorry, I’m so sorry to be late!” Then she turned and looked at me and said, “What are you doing sitting down there? Get up and let your father sit down!” My father said, “Well, I’m afraid he got a bad back.”

“Well, that’s not a really good start is it, young man?”

Well I didn’t get on terribly well with her, she was very bossy. She said she could arrange for me to go to her school but I’d have to pay and my father said, “Well he hasn’t got any money and I’m not giving him any money, so I don’t see how this might work.”

The next day I saw Kurt Joos and he had a very different story. Partly because he was desperate, like everyone, to get boys and men in the company with the war, because they’d all been conscripted into the army. He was marvellous. He said, “I want you to come up to Cambridge.” It was the Red Lion Hotel, the room upstairs and just, “See how you are and how you can move around” and all that. The pianist came in and improvised and I was told to improvise, which I did. Hurled myself around. He was quite impressed and he said, “Well, I could take you on as an apprentice but you have to work hard.”

I said, “Ooh, wonderful, wonderful!” and I thought, “I’m getting right into it.” And it was a marvellous beginning for me. I was immediately in theatre.

Natalie Steed: So what did you do for them? What kind of jobs did you do for them?

Peter Wright: I used to have to work the follow spot, I used to be tea boy, and I always getting the scenery in and out when we went on tour. I use to have to change the lights on the side lights on the side of the stage. I was general dogsbody, which I liked for a certain amount of time. In the end I was finding I was doing much more of that sort of work than training. In those days you can imagine there were no rehearsal rooms. None at all. If there was any space to dance the floor would be terrible and it would freezing cold, it was not ideal for anyone to start training. Then I had to stop because my back got worse and worse and worse. Went back, and as soon as I went back I was called up and I had to go into the army. Went into the army, had another really bad fall. They finally came to me and said we’ve decided were going to discharge you. You’re too much of a liability. I said, “Oh, good!”

Anyway, at least I got out of the army and everything and I started again. But I very quickly realised that I was actually getting nowhere fast because of the terrible facilities and also the sort of training you’re getting wouldn’t do me any good with any other company. A lot of the training was wonderful. The sort of dynamics of movement was superb. And actually it has helped me later on. Not just when, er, it’s me dancing but also doing a bit of choreography and everything

Natalie Steed: So when you were discharged from the army did you go back to Ballet Joos?

Peter Wright: I went back for a short spell but I almost immediately went down to see Vera Volkava. I actually heard about her through another well known dancer called Peggy van Praagh, who became the director of the Australian Ballet later. She was our director at Sadler’s Wells Theatre Ballet. She said well you can come and do my classes in the day and I said, “Right, I can’t pay you very much.” At that time the classes, the daily classes, were three shillings and sixpence. She said, “I want you to pay half because it will make you work harder if you feel you’re actually paying for it.” So I managed to do that and I got jobs in musicals and this and that. She taught me everything and it was a very good start to classical ballet.

Then, being in that studio, we would hear about new jobs going and new companies. There were several new companies that were coming up like the St James’ Ballet and like the Metropolitan Ballet. I managed to get into those. Volkova wasn’t very keen she said, “You must stay here. Stay, learn, get it right.”

And it was through the St James’ Ballet that I met John Cranko who made a great difference to my life, to my life later on and at that time. Because he had a role in this particular ballet which was called School for Nightingales. It was a school for young lady singers in, sort of, an eighteenth century school. I was the naughty boy who broke into the school and caused havoc. I absolutely loved it.

John had said to me, “You know, you really ought to try and get into a proper company. You can’t go on forever in little companies like that.” He said, “I think Sadler’s Wells Theatre Ballet”, where he was working on choreography, and as a dancer, he said, “I think you all should audition for de Valois”.

I said, “Ooh yes, I’m game for that.” Anyway, he arranged when we were in St Albans for de Valois to come and see his ballet. And, hopefully, also she could see me.

Well, it was the most disastrous time because, in those days, if you had a sort of more made-up look, we used to blot out our eyebrows with thick soap so that they would get matted and then you could put some make up on them and then powder. Then you could make your own different shapes. Knowing that de Valois was coming I spent a long time getting myself really perfect. Warmed up, everything. It was a hot night and I could see de Valois there. She was sitting in the front row. I could feel the perspiration coming down, trickling down and I was prancing around and it all went into my eyes. I couldn’t see anything. I absolutely messed it up. And I couldn’t shout out and say I’m terribly sorry. Of course de Valois did not get a very good impression of me at all.

But I thought, “Well, the next day I’m going to ring up and just see if I could have an appointment to go and talk and apologise.” I rang up but I didn’t get any joy because it was her secretary, Jane Edgeworth. I said, I need to talk to Miss de Valois. She said, “Oh? What about?” “I want to talk about coming to see her after she’d seen my performance last night.” Then I realised at once she’d already heard about it. She said, “Well, I don’t think that is going to be possible.” I said, “Will you please tell her that I’m here and that I want to…”

Anyway, she went and then came back and said, “I’m afraid that Miss de Valois said that you’re not a good enough standard to audition.”

I wouldn’t accept that and then I talked to Peggy van Praagh at Sadler’s Wells, who I knew. She said, come back on the Thursday, Madam is always there. I went on Thursday, no Madam, so I did the class. Next Thursday, no Madam, but Ursula Morten the Assistant Director was there, who thought I was a bit wild but said she would report back. Anyway, the third Thursday and finally the last fifteen minutes de Valois appeared, but also in the class were five other very professional looking boys, all dressed perfectly and I was, I think I was, I used to still wear football shorts in those days. Anyway, I did my damnedest in that when she was there and we had to queue up outside to see her. The others went in and they all came out with long faces. I went in, “Now come here young man! I think you’re just the sort of boy I’m looking for.” Well, I was amazed.

Natalie Steed: Did you own up to…?

Peter Wright: No. Never. Anyway, she said “Well I would like to have you in the company but I’m afraid there are no vacancies.” She said, “You can go to the school.” And I, of course, said, “Go to the school?” Having been in a ballet professionally, I said, “But I am a professional!” She said, “Young man, I’m making you an offer, take it, or leave it.” “Oh, yes madam..I’ll…” But she did promise she’d get me into the company within six months. Well, she got me in within six weeks actually.

The transcript of this podcast may have been lightly edited for ease of reading.