Christopher Wheeldon

Christopher Wheeldon talks in 2003 with his former classmate and Royal Ballet First Soloist Jane Burn. Christopher speaks about his early years in dance with candour and charm, mentioning Anatole Grigoriev, his teacher at White Lodge, and his early forays into choreography with the inspirational Norman Morrice. The interview is introduced by his former colleague Darcey Bussell.

First published: March 23, 2025

Biography

Christopher Wheeldon was born in 1973 in Yeovil, Somerset. He started training as a dancer from the age of eight. From 1984 until 1991 he attended The Royal Ballet School, winning the gold medal at the Prix de Lausanne in 1991. That same year he joined The Royal Ballet. In 1993 he joined New York City Ballet, becoming a soloist in 1998.

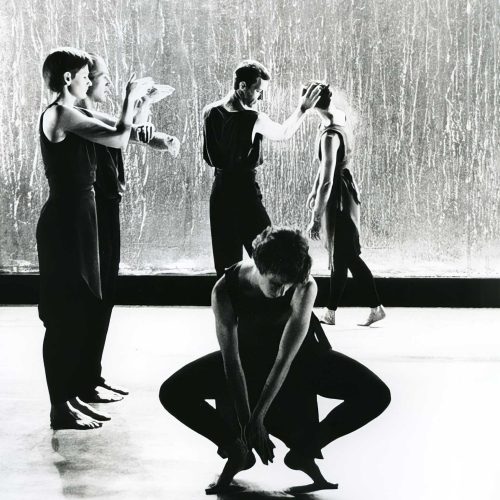

He began choreographing for New York City Ballet in 1997, retiring from dancing in 2000 to concentrate on choreography. In 2001, Wheeldon became the New York City Ballet’s first resident choreographer and first resident artist. From 2006 until 2010 he also ran his own company, the Morphoses/The Wheeldon Company.

Aside from his work in New York and also in London, Wheeldon has established himself as a choreographer worldwide, including works for San Francisco Ballet, The Bolshoi Ballet and National Ballet of Canada. In 2011 he choreographed Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, The Royal Ballet’s first full-length commission for 20 years, followed in 2014 by The Winter’s Tale. Other commissions include Strapless (2016) and Like Water for Chocolate (2022). In 2014 he directed and choreographed a musical version of An American in Paris, first performed in Paris, then in New York and London. He was awarded an OBE in 2016 for services to dance.

Transcript

In conversation with Jane Burn

Christopher Wheeldon: Actually, really, the first exposure that I had to any kind of dance was probably my parents. My father was a director of amateur dramatics at the time. He would direct plays in our living room and there would be little sort of dance interludes in those, not really on a professional level, but and then really, the very first time that I remember seeing ballet was with Frederick Ashton’s La Fille mal gardée on the television. Funnily enough, when I did audition for the Royal Ballet School and I got in as a junior associate. We did learn the chicken dance from La Fille mal gardée. And I was very disappointed to learn that the chickens were actually old women, although at that stage I did get to dance the role of the cockerel. I danced for about six months in a village hall in East Coker in Somerset with a teacher who was, who was teaching the RAD (Royal Academy of Dance) syllabus. My teacher said, well, perhaps in a couple of months you might be ready to audition to become a junior associate. Obviously, she had seen something in me that was out of the ordinary. I did, in fact, go up to London and audition as a junior associate for the Royal Ballet School, which is the sort of preliminary, twice-weekly classes for students who are not quite yet old enough to go to White Lodge, which is the Royal Ballet Junior School. I had the Camilla Jessell book, Life in the Royal Ballet School. Somebody gave me that for my birthday, I think the first year that I was dancing. So I had that and I looked through and a couple of times I’ve been up to London with my parents to see, I think, a play or musical or something. And we’d driven through Richmond Park and we’d stoped at the gates of the school and looked in. And I distinctly remember a moment saying to my mum, this is where I want to go. You know, at 8 years old, it just felt absolutely right.

Jane Burn: So you were taking classes with the junior associates on a weekly basis now?

Christopher Wheeldon: Twice a week, Thursday and Saturday. And we were driving up from Somerset. And that was only for a little while because then actually my dad’s job moved. So we moved closer to London and continued to go twice weekly to the Royal Ballet School, having always having to finish prep school early, which always kind of instigated this long stream of questioning from my friends. Where are you going? What are you doing? Of course, at that stage, I was only 10, 9 or 10, and I was certainly not going to admit that I was going to ballet classes. I auditioned for the Royal Ballet School, having been a junior associate for 2 years, auditioned for White Lodge to the lower school. And I still had about 6 months left at prep school in Guildford. And when the letter came through, the acceptance letter for the school, my mother told my headmaster that I’d been accepted to the Royal Ballet School and I would therefore be leaving Lanesborough Preparatory School for Boys and wouldn’t be going to the Royal Grammar School. And he was so proud that he just announced it to assembly one morning. And I still had 6 months to go at school and the next 6 months were fairly hellish.

Jane Burn: What were your goals at that time? Where did you hope that this training would take you?

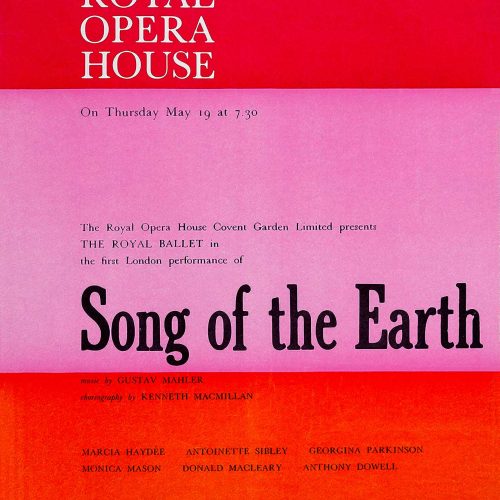

Christopher Wheeldon: I mean, obviously I always hoped that it would take me into a career as a dancer, particularly with the Royal Ballet. I mean, the focus was very much the Royal Ballet. We were at the Royal Ballet School and we were taken to see the Royal Ballet. And we were, I was watching dancers Anthony Dowell was still dancing then. And Jay Jolley and Mark Silver and then Bruce Sansom. And these were all dancers that I was inspired by. Even though the goal, of course, was to be a professional dancer. It was very much kind of a stage by stage, you know, and it was almost like a step by step as we learnt new steps. And in the ballet vocabulary, the goal was to achieve a double pirouette and to achieve, you know, a single tour and then to achieve a double tour. You know, it was very kind of almost week by week. The first two years. My teacher was Pauline Wadsworth and then Pauline retired and Anatole Gregoriev from the Kirov took over. And he was my teacher from the third year to the fifth year, at White Lodge, so for 3 years. And it was a totally different dynamic. It was an amazing leap. It was a leap jumping from having a female teacher, to having a male teacher. And it actually came at the perfect age for me because by the time I was in third year, I was just 13. 13 or 14. And that’s why you’re really starting to tackle the more demanding aspects of male dancing and you are starting to learn how to turn and jump, and you’ve gone past that sort of the stage of learning how to control well, I mean, you’re really still learning about the control of your body, but those first couple of years are so important, learning just the very basics of ballet. Then to have this towering kind of force at the front of the room, it was frightening. But kind of, it was it was fairly awe inspiring. I remember we likened him to Arnold Schwarzenegger because he just felt like this giant man to us.

Jane Burn: What performing experience did you have at White Lodge?

Christopher Wheeldon: Well, my first performances at the Opera House were as a junior associate. I was in two operas. I was in Falstaff and Rigoletto. I think actually the very first sign of me being rather bossy was at a performance of Rigoletto, when the tenor missed an entrance in the first act and suddenly the orchestra leapt, basically they leapt over our little dance, which is the Perigordino dance in the first act and quite determined not to miss my moment on stage. I grabbed the other two little boys who were in the Perigordino dance, and we ran out on stage and we danced. We did the Perigordino dance only not to the Perigordino music, but to the aria of the tenor. And of course it must have just, looked, absurd. And I think we were completely in his space, but there we were. I kept saying “hold hands, on to the next step”. But then at White Lodge. We started, Nutcracker – it was the first year of Peter Wright’s new production of The Nutcracker. And I think that the second year White Lodge. So there was great excitement about that. It was exciting, but it was frightening because everyone was afraid they weren’t going to be in it. And then, of course, if you weren’t in The Nutcracker, then that was, at that age, that was kind of like, you know, that just proved that you weren’t worth anything because because you had to be, you know, because all the best people were in The Nutcracker. And once you were in The Nutcracker, it was what you were doing in The Nutcracker. If you were just a soldier or if you were a Second Act page, if you were a Second Act Page, then you were better than just being a soldier. So I was A Second Act Page, what can I say. The second year, Peter decided to have the children, the child roles, Clara and Fritz, which the first year had been danced by company members, danced by children. So then, that was huge because Clara was the lead of The Nutcracker and Fritz was the naughty brother. And and, and I, and I actually got to dance to dance the role of Fritz. So.

Jane Burn: How did that feel?

Christopher Wheeldon: Oh it felt great.

Jane Burn: Did you ever at this stage think that you would like to choreograph a ballet?

Christopher Wheeldon: I actually choreographed a little piece as a junior associate. We ended up performing this little piece that I choreographed at a primary school. We went off to do a demonstration. So that was my first public performance. I was 9 I think.

Jane Burn: Were you pleased with the result?

Christopher Wheeldon: Oh, yes. Yeah, insecurities hadn’t crept in then. And it was a prequel to Swan Lake. It was the Swans hatching out of the eggs.

Jane Burn: And you had opportunities to choreograph at White Lodge?

Christopher Wheeldon: Yes, right from the beginning there was a junior choreographic competition once a year, and then after third year, a senior choreographic competition. And I was involved in those every year. The first year that I choreographed, I choreographed a ballet called The Syncopated Clock to music by Leroy Anderson, and it was performed for Princess Margaret. And that was, I mean, that was a huge prize. I mean, I couldn’t believe that, along with Michael Rolnik, Michael Rolnik choreographed Leaves Are Fading and not Leaves Are Fading, but something to do with leaves. And it was Darcey Bussell and Alistair Marriot and William Trevitt. And that was my first year at White Lodge. So that was quite, quite amazing. And I think that was probably quite a boost as well. Made me think, “Oh, next year I’m going to do something more ambitious. Perhaps we’ll get to perform it for the Queen.” Norman Morrice, he was in charge of choreographic studies all the way through, through my time at the Royal Ballet School. Every now and then there would be a little session with Norman. He would always take a look at what we’ve been doing and we’d talk about it. And, but it was never, he never criticised, ever. It was always encouragement as opposed to criticism, even in the later years, although actually the Upper School and when, you know, when it was when we were taking it far more seriously, he would criticise. But it never felt like criticism. It only ever felt like encouragement. Choreographing started to sort of inch its way up in importance to me almost. It was almost as important as dancing at that stage. Although still my goal was to be a principal dancer with the Royal Ballet. I think actually …it was interesting because at that stage, not having worked with a choreographer, my perception of the creative process with other people, was probably rather forced. I think I probably, actually, had picked up a lot from my relationship with my teachers, and that it might have made me a little overly arrogant at that stage, that once I was the person sitting at the front of the studio, I was the person in control. And there was never, it was never really, and an incredibly, sort of, at that stage, collaborative thing. I mean, I remember us having a lot of fun, but now, thinking about how I work in the studio and how much I rely on my dancers not to make the choreography, but to be a part of the process and to be engaged in creating a movement and making sure that the priority is creating a movement for a particular person or creating a role for a dancer, as opposed to just sticking steps on them, back at school. I suppose I probably had a lot of ideas in my head that I just needed to get out. It was … they were unfocused and probably fairly free flowing. And now that I sit here and I say all of that, I think, gosh, how good it was to be at school and to have those, you know, those sort of unfiltered responses.

The transcript of this podcast may have been lightly edited for ease of reading.