David Wall

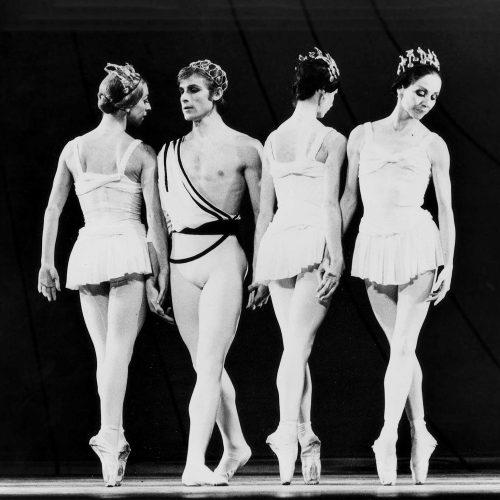

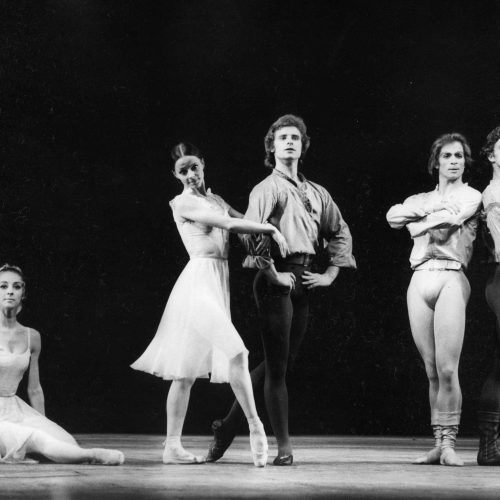

David Wall was one of the greatest male dancers of his era, with an extraordinary stage charisma, range, theatricality and honesty. In this interview he talks to Frank Freeman, a former colleague, about his early training and his work in the Royal Ballet Company, which included partnering Dame Margot Fonteyn at the age of 19, and having major roles created on him by Sir Frederick Ashton, Antony Tudor and Sir Kenneth MacMillan. He also gives us some insight into his enthusiasm for theatre and his friendship with some of the great actors of the time. His whole life is present in his voice, no sophistry and every inch a prince.

First published: May 5, 2025

Biography

David Wall’s career in dance began with ballroom dancing classes, followed by ballet classes with Mrs Durnsford in Windsor. Training with the Royal Ballet School began when he was 9 years old, and he joined the Royal Ballet Touring Company in 1963. He was appointed Principal at the age of 20, the youngest in the history of the Company, having already partnered Margot Fonteyn in Les Sylphides at the age of 19 and going on to perform Swan Lake with her the following year.

He joined the Royal Ballet at Covent Garden in 1970, where he continued to partner Fonteyn frequently, as well as Doreen Wells, Lynn Seymour, Natalia Makarova and all the principal ballerinas of the time. His male colleagues included Rudolf Nureyev and Sir Anthony Dowell, whose brilliance in no way overshadowed his own.

While in the Royal Ballet, Wall worked with many choreographers, including Dame Ninette de Valois (Rake’s Progress), Frederick Ashton and Antony Tudor. He is often remembered for his work in some of the heavily dramatic ballets of Kenneth MacMillan: Romeo in Romeo and Juliet, Lescaut in Manon and Crown Prince Rudolf in Mayerling, the last two roles having been created on him, but he also excelled in lighter pieces, such as La Fille mal gardée, The Two Pigeons and Coppélia, aside from achieving great acclaim in the classics such as Sleeping Beauty, Swan Lake and Giselle.

Wall retired from dancing at the top of his career in 1984. He was then Assistant Director and Director for the Royal Academy of Dance until 1991. In 1995 he began to work as Ballet Master for English National Ballet until 2011, though he continued to coach both there and for the Royal Ballet. Wall was married to the ballerina Alfreda Thorogood and they had two children. He was appointed CBE in 1985, and died in 2013.

A charismatic presence on stage, in whatever type of role, tragic, noble, sinister, light-hearted, he was always technically impeccable, as well as acutely sensitive to the essence of a work. He was thus able in his later years to pass on his insights to the next generation of dancers.

Transcript

In conversation with Frank Freeman

David Wall: I didn’t come out of the womb wanting to dance. I remember quite strongly images of my waltzing and fox-trotting, and polkaing around the school hall. Having done that, Miss Durnsford, who used to teach ballet at the weekends, asked my mother if I’d like to come along to her ballet classes. So I went to her classes on a Saturday morning in Old Windsor and started my classical ballet training with her at the age of-, I think I was about five and a half. One memory I have of her is trying to teach me for the first time rond de jambe á terre, and in those days dance teachers didn’t have proper dance studios, and her studio in fact was her front room, and I remember her taking a carving dish off of the wall, placing it on the floor, and saying, ‘I want you to trace round this dish,’ and that became my rond de jambe á terre.

It wasn’t until a couple of years later when I was at the Associates that I actually saw my first ballet performance.

Yes, it was Prince of the Pagodas, John Cranko’s production at the Opera House.

Frank Freeman: And that was with Svetlana Beriosova?

David Wall: Svetlana Beriosova, David Blair, being very young, the music I found very [ …?] and my lasting memories of being in the Opera House was actually the red velvet plush around the circle, which I thought was very nice.

Frank Freeman: How did you get to White Lodge? Was that a natural progression from the Associates?

David Wall: Yes, I spent a year, I think it was, with the Associates and I remember having to do quite a formal audition, and some intelligence tests which I failed dismally at, but I was taken into White Lodge for the opening of the school, and spent the next six years there. The teacher Sarah Payne, who taught me as an Associate, moved to White Lodge and I had her for four years at White Lodge. So she, I think, holds a responsibility for the way I turned out. I hope she was pleased.

And then we used to travel to Barons Court from Richmond to do classes with Errol Addison which was a great thrill.

Well, with Errol, one enjoyed the freedom of dancing more. And his exercises, although initially were very correct, he used to have wonderful finishes at the end of them. Especially at the bar, you’d be doing a very staid battement tendu exercise or jeté exercise, and suddenly you’d all run into the centre and pose in an arabesque.

Frank Freeman: Then you graduated to the upper school, and-,

David Wall: Yes.

Frank Freeman: How long were you at the upper school?

David Wall: Well, it must have been a year, but in fact the touring company was working in London during the latter part of the academic year and I remember we were always being used as extras at Covent Garden, which got us a taste.

John Cranko’s Antigone, we used to come on with black cloaks. That was the ballet that really inspired me, from the male point of view, because the male roles in that ballet were lovely. It was a very, very exciting time, and of course Fred-, Sir Frederick the year before had just created Fille mal gardée. It wasn’t until actually seeing Fille mal gardée that I actually realised what could be achieved from a male dancer’s point of view.

Then John Field invited myself and John Ryder, and, Piers Beaumont, Garry Grant, to join the company. That was 1963 and I was 17 .

Frank Freeman: Do you think it was an advantage, going into the touring company rather than going into the main company, for you personally?

David Wall: I was just very happy to get a job. In retrospect, it was an enormous advantage, because the 7 years that I was in the touring company I got so much under my belt as far as variation of roles, and repetition of roles. In those 7 years, it would have probably taken me 14 years to do that number of performances in the resident company.

My first role was in Coppélia, that was [Ninette] de Valois’ production.

The repertoires used to really consist of a neo classical ballet, i.e. Coppélia, Fille mal gardée. Lighter ballets. Two Pigeons. Then we used to perform during the course of the week also a classical ballet, which was either Swan Lake, Sleeping Beauty, and then A vast range of one-act ballets. [Kenneth] MacMillan pieces which were Solitaire, Danses concertantes. He created a ballet on the company called Création du Monde. [Frederick] Ashton created Sinfonietta.

Frank Freeman: Can you remember what your first principal role was?

David Wall: The Invitation.

Frank Freeman: That’s by Kenneth MacMillan.

David Wall: Kenneth. Patricia Ruanne and myself both did our first principal roles as the young boy and the young girl in The Invitation. Classically, Sleeping Beauty was my first prince role, and then Two Pigeons was my first [Frederick] Ashton ballet.

On one occasion when I was young, I persuaded Dame Ninette de Valois to give me the title role in Rake’s Progress. Which I must say I found an enormous challenge, and initially didn’t want to do it, because I didn’t think I had achieved any artistic or acting ability to sustain such a demanding role.

Frank Freeman: John Field was your, I think your director and your mentor, and how did he influence you?

David Wall: It was a great time for directors. Peter Hall had just taken over Stratford-upon-Avon. Wonderful things were happening in the live theatre, and John, being somebody that adored live theatre, wanted ballet and his company to reflect very much what was happening, and took a lot of chances. Me being one of them, which I’m eternally grateful for.

I’ll never forget Celia Johnson coming to see Romeo and Juliet at the Opera House. I’d met her through Tom Courtenay, and it was the first time she’d seen the balletic version, and she was so amazed by what could be done physically with Shakespeare. She was very, very, very moved, and likewise most of my friends in the theatre world, Rodney Bewes, Tom Courtenay, Albert Finney, John Hurt, I used to see their work and they used to come and see our work, and it was a great mixing pot of ideas.

Frank Freeman: You were saying that John Field took risks, and perhaps one of the big risks is in that he instigated your dancing with Margot Fonteyn at the age of 19 ?

David Wall: We were doing a tour of Scandinavia and Europe, and Keith Rosson, who was partnering Margot in Les Sylphides, couldn’t go to the Finnish part of the tour, and John suggested that she did it with me.

Frank Freeman: What was your reaction when you were told?

David Wall: Fear and trepidation. I’d always held her in enormous awe and there I was in the same studio and it was gorgeous. I mean, she broke down any inhibitions I had. And then after that, she came and did a tour with the company and I was fortunate in dancing Swan Lake with her.

Frank Freeman: Then later you did – did, she chose you to be her partner on many foreign tours?

David Wall: Yes, yes, varying roles. Berlioz’s Romeo and Juliet, Kenneth [Macmillan]’s Romeo and Juliet at Covent Garden, Swan Lake, Sleeping Beauty. I did her final full length version of Sleeping Beauty in Rio with her, the last time she actually danced a complete Sleeping Beauty. It was a wonderful occasion.

Frank Freeman: You must have got to know her very well?

David Wall: Yes. She and I laughed a great deal together. All of the memories I have with Margot is when she was laughing. When we were performing on the West Coast, we opened the World Fair in Spokane, and our next venue after Spokane was Vancouver, and Margot didn’t want to travel the day of the performance to Vancouver. So we decided that we would go after the show. So we finished the show in Spokane, and flew to Seattle. And then she, we, decided that we’d arrange for an ambulance to take us from Seattle to Vancouver, which was very comfortable, because we could both lie down, and we arrived in Vancouver at 6 o’clock in the morning. Went to sleep in our hotel rooms, got up for a late lunch, and unfortunately, the company had found that when they got to Seattle it was fog bound, and that they couldn’t fly from Seattle to Vancouver, and in fact, they were having to arrange for a coach to do exactly the same long journey that Margot and I had done. So Margot and I were sitting in the theatre at 7 o’clock in the evening and there was no company.

So Margot said, ‘What are we going to do?’ I said, ‘Well, we have tape recordings of both Sleeping Beauty and the Romeo and Juliet pas de deux. What I suggest we do is that we dance the Romeo and Juliet pas de deux, the curtain comes down, and I explain to the audience the dilemma we are in, and then I will sit and talk to you, and interview you in front of the audience and then we can do Sleeping Beauty after that,’ and she thought it was a wonderful idea. So we were settling down to do this, and thank goodness, at a quarter past seven, this is supposedly for half past seven curtain up, the company arrived on their coach.

Frank Freeman: You said that Sir Fred created Sinfonietta on you. Can you talk about that? Was that the first time you’d worked with him?

David Wall: That was the first time I’d worked with him in close proximity. It was fantastic. It was a bit of a rushed process because we were on tour. But I got myself into a lot of trouble, actually, after that, by saying that I didn’t feel – I was doing an interview – and saying that Fred wasn’t really a choreographer, he was more a sculptor, and I remember John Field saying to me, ‘I think you should write Sir Frederick a letter of apology.’ I said, ‘Well, it came out of a conversation, John, that, you know, that’s how I felt Fred choreographed, sculpturally.’ He said, ‘Yes, we all know that, but to have it in print. You need to write him an apology,’ to which I did.

Frank Freeman: And this was 1967?

David Wall: And Antony Tudor, of course, came and worked on Knight Errant. He and I got on wonderfully well together, and he became very, very close to Freda [Alfreda Thorogood] and myself. I loved his honesty.

Frank Freeman: What was he like to work with? I mean, how did he create the role on you?

David Wall: He wasn’t terribly explicit. He didn’t work in terms of vocabulary, you know, ‘I want a chassé pas de bourrée step change,’ you know, he didn’t work like that. He used to demonstrate and see you make a move in the way he’d demonstrate it, and sometimes when he did demonstrate it, you didn’t know what on earth he was wanting, but slowly he’d get the movement he was requiring out of you. More than that, when he’d actually produced the piece, in retrospect, it was like he’d unzipped you from the throat to the navel, and had produced your personality to the audience without you knowing about it. Obviously there was a creative process, but I can’t really pinpoint how it was done. He would move and shuffle, and change your body here and there, and ask you what you were thinking while you were doing a certain movement. You’d say to him, ‘Oh, I’m thinking of tea, which is in 10 minutes’ time.’

Frank Freeman: The first time you worked with Sir Kenneth MacMillan [was] when you created a role was in Anastasia in 1971, and what was your -,

David Wall: That’s right. Anthony Dowell, Michael Coleman, myself and I think, I can’t remember the fourth person, we were the four officers in Anastasia. And it was a difficult time, I think, because the company was still very unsettled. The two companies had, as I say, merged, but it wasn’t an altogether happy merging. There was still a little bit of in-fighting.

Frank Freeman: Then in 1974 Sir Kenneth made the role of Lescaut on you in Manon.

David Wall: Hmmm. Kenneth-, Kenneth was-, relied quite a lot on Dame Ninette’s input into whatever he was doing. I remember she came to watch an early rehearsal, and suggested that there wasn’t enough humour in the ballet, hence the drunk pas de deux with Lescaut and his mistress, because that was originally choreographed as a straight pas de deux with variations.

And it was, funnily enough, it was harder to change what had originally been choreographed into a lurching drunkard than it was to originally choreograph the steps

Frank Freeman: So are you saying that Madam [de Valois] saw the whole ballet?

David Wall: She saw the whole ballet and, sort of, made some suggestions to Kenneth.

Frank Freeman: So that solo of yours which is very famous,

David Wall: Was originally a straight solo, yes.

Frank Freeman: Then in 1978 you were cast as Crown Prince Rudolf in Mayerling which is, must be one of your greatest, greatest roles.

David Wall: Because he was such an anti-hero, one couldn’t just play it as an anti-hero. One had to try to get the audience to understand at least the dilemmas, and actually have a bit of simpatico with the character. We had real people that we had to portray on the stage. When I was trying to grab hold of what sort of a character I was going to be portraying, of course I was reading all of the books that were necessary, but every book had a, like any history book, has differing opinions. I then read a book about his early childhood, and his sort of upbringing, where he had a tutor that used to come into his bedroom at 3 o’clock in the morning and fire a gun, and of his mother seeing him marching in the snow at the age of 6, and the fact that he never saw his mother. So I thought, well, rather than that was where I was going to try to form the whole ballet from, was the information that I’d absorbed from his very early childhood.

Frank Freeman: I mean, the stamina required for that role is awesome. Were you aware when you were making it just how …

David Wall: No, I wish I had been. I might still be dancing now, it was, I often felt, I often felt sad that, you know, memories are going to be of me in Mayerling when I’d spent, you know, 20 years of my career trying to make the princes come alive, and Romeo and Juliet be real, and bring that sort of stability to the profession, but I mean that’s par for the course. I mean, you know, what I used to find earlier on was that it was really quite, quite important that people saw me as Albrecht, and not just as David Wall being Albrecht.

The transcript of this podcast may have been lightly edited for ease of reading.