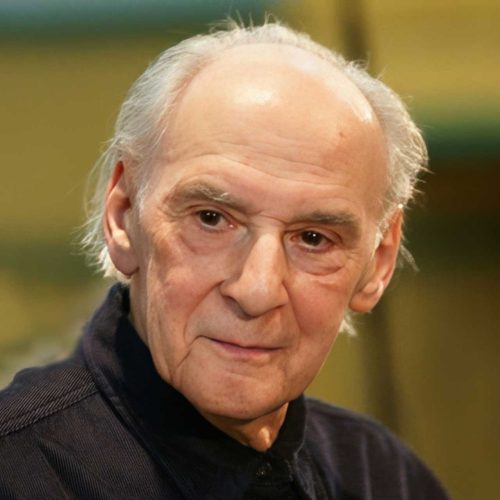

Pamela May

This ‘voice’ of British Ballet is that of Pamela May. She was born in 1917 and after retiring as a ballerina with The Royal Ballet became the teacher par excellence for generations of Royal Ballet School dancers. May, interviewed by Patricia Linton, starts this clip by describing being a student herself in 1932 and watching Adeline Genée, the great Danish ballerina, and also the first President of the Royal Academy of Dance, perform a minuet with Anton Dolin on tour in Copenhagen. The interview is introduced by Alastair Macaulay.

First published: October 28, 2025

Biography

Pamela (Doris) May was born in San Fernando, Trinidad in 1917, where her father was an oil engineer. The family returned to England in 1921. She first studied ballet with Freda Grant, and later in Paris with Olga Preobrajenska, Lubov Egorova and Mathilde Kschessinska. She joined the Vic-Wells Ballet School in 1933 and made her debut with the Vic-Wells Ballet in the pas de trois from Swan Lake in 1934.

May became a principal with company and danced the whole gamut of the repertoire, including creating many roles, until she retired from dancing ballerina roles in 1952. She then became a leading mime and character artist and stayed with what became known as The Royal Ballet in this capacity until 1982. All this happened alongside her teaching at The Royal Ballet School from 1954 until 1977. Pamela May was appointed OBE for services to dance in 1977. She died in 2005.

Transcript

in conversation with Patricia Linton

Pamela May: Ninette de Valois had been invited by Dame Adeline Genée, who was patron of the Royal Academy of Dancing, to take a small company to Copenhagen in honour of our Prince’s visit there – the Prince of Wales – and she accepted, naturally. Her company then, the Vic-Wells [Ballet], was very small and she wanted five extra corps de ballet, and she came to the Royal Academy of Dancing to audition. Anybody who’d got the advanced could audition. So, me at 15, luckily! And I passed and she took me as one of the five girls. So, I had a very strange beginning. I was dancing in the company before I was even a student! I went to Copenhagen with the company, and I was in Les Sylphides and Job and Fête Polonaise, and I loved them all.

So, I went back a year, I was just 16 then, to the school [Vic-Wells Ballet School]. But, of course, the minute she had me in the school and Les Sylphides was in the programme, I was in and on, and dancing away in Sylphides, as well as being a student. Then Job appeared. I was in Job. This went on for the next year. I was in performances, but I was a student. My mother and father got a little bit annoyed. They wrote to Lilian Baylis saying: ‘Now that Doris May,’ (as I was then) ‘is in so many ballet performances, surely we need not have to pay any more for her as a student?’

Lilian Baylis wrote back immediately saying: ‘No. No more paying’. I was to be taken into the company.

Patricia Linton: Could you tell me a little bit about student life at that time, who your peers were and who actually taught you when you were in the school?

Pamela May: Yes. I hadn’t been there very long when Margot [Fonteyn] arrived. I remember her in class very well, so neat, tidy, black hair. Her mother used to often come and watch the classes. I remember Julia Farron was then in the company and Leslie Edwards, Joy Newton, Harold Turner was there in the company, Walter Gore, Beatrice Appleyard.

Patricia Linton: These were the original…

Pamela May: All the original company. The classes were taken by Ursula Moreton – our classes. The students were nearly always [taught by] Ursula Moreton and Ailne Phillips, who was known as ‘Babs’. Also, at that time [Stanislas] Idzikowski used to teach a lot and I remember even beginning to learn pas de deux with Idzikowski.

Patricia Linton: Can I just go back one tiny bit, to 1932, when you made this trip to Copenhagen, before you’d even joined the school. Is it true that Adeline Genée actually danced there?

Pamela May: Yes, she actually danced, in that she did a minuet with Anton Dolin.

Patricia Linton: Do you remember how she looked?

Pamela May: She looked so elegant. Not very young, she was getting on, but great dignity and charm and a beautiful smile. But it wasn’t actually kicking her legs and dancing around, it really was only a terre-à-terre minuet: beautiful curtseys and things.

First ballet I saw Dame Ninette dance, which was before I was actually in the company, was Coppélia. And we were the friends, six friends. But because the company was so small, we had to do the friends, which is pointe work and then rush into the wings and put our character shoes on and come back and do the Mazurka and the Csardas. So, we were pointe-work, character work, pointe-work, character work. But I remember watching her dance and she had beautiful feet… her brisées across the stage were gorgeous.

Patricia Linton: What about Markova, Alicia Markova?

Pamela May: Well, she was the ballerina then, you see. In those days, all the Giselles were done by Markova, and I thought she was lovely. They used to do a divertissement programme, when she did [the] Aurora Pas de Deux [the pas de deux from Act III of The Sleeping Beauty] by itself. I remember watching her walk around the stage in that, I thought, ‘one day I’m going to do that pas de deux’.

The other person who was lovely to watch was Pearl Argyle, who had come from the Mercury Theatre, Ballet Rambert. In fact, The Gods Go A’Begging was done on Pearl Argyle originally. She was the girl, and I remember learning it from her. And she did Aurora Pas de Deux. Elegant! The walking as so beautiful. One learned so much by watching these ballerinas. And, again, by watching the rehearsals. [Frederick] Ashton adored her and did a lot of rehearsals with her.

Patricia Linton: Can we talk a bit about Ashton now, in the 1930s?

Pamela May: I did a lot of dancing with him before he actually gave up dancing. And, although he wasn’t terribly strong, it was quite amazing how well he partnered, because he was so musical and so long as he was with someone who was equally musical, the lifts and everything were just so light; you know, you just went up with the music. I had him first of all when he did Apparitions and he was my partner, and we galloped round and round the stage!

Patricia Linton: You had a wonderful year in 1937 with Les Patineurs, with A Wedding Bouquet and with Checkmate.

Pamela May: I remember Checkmate very clearly, because the first night of Checkmate was in Paris, and I was the Red Queen, actually – I didn’t do the Black Queen until later. And it was a great success, which was interesting because Dame Ninette said, ‘We never have a success in Paris, they don’t like the English’. But they did that time. We were at the Champs-Elysées Theatre.

Patricia Linton: When you were in Paris, was that the first time you went to study with some of these great old Russian ballerinas?

Pamela May: First time? In 1937! Good gracious no! First time I went was with Margot and her mother, when I was about 17. Long before that. We used to go every summer right ‘til before the war. And Margot’s mother used to drive us to the South of France after, and we used to have a lovely holiday, swimming in the Mediterranean.

Patricia Linton: So, you studied with Kschessinska?

Pamela May: Kschessinska.

Patricia Linton: Egorova?

Pamela May: Egorova.

Patricia Linton: Preobrajenska?

Pamela May: Preobrajenska. I suppose, in a way, our favourite was Preobrajenska, and we nearly always went to her first class in the morning at 10 o’clock. It was a wonderful all-round class. Her adages and port des bras were gorgeous. You were kneeling and praying, and all that sort of thing. Kschessinska we always went to rather late in the afternoon. She did a 4 o’clock class and we were always a bit tired, but she kept us jumping. Jumping and jumping and pirouetting and jumping! And then Egorova came in between both. She was quiet. She loved adage and port des bras and she corrected your arm positions in everything, jumping and adage.

Patricia Linton: 1939 and we got to The Sleeping Princess [The Sleeping Beauty] and then came the war. Perhaps we should talk now about, were you on that fateful tour to Holland?

Pamela May: Yes. They [the Dutch authorities] made us live in The Hague in one hotel and we went out to each place by coach. Two coaches to take the whole company, and the night of the invasion we went to Arnhem, and we got back to The Hague about 3 o’clock. At 3 o’clock they [the German army] entered Arnhem – so we were just three hours ahead of them. And the planes were overhead, and they were dropping leaflets and papers and things. And we had just about got to bed when the planes started. We all got up, threw on our clothes. A lot of people hadn’t even bothered to undress, they were worried, you know.

Patricia Linton: I was going to say was there ever a point when you thought you might not get back?

Pamela May: Well, I think they thought that all the time. Non-stop. Will we ever get out of The Hague?

Patricia Linton: So, it was very, very frightening?

Pamela May: And we all went down into the basement, you see, and we couldn’t even get to the loo there. We had to go up one flight and Ninette wouldn’t let us go to begin with. Anyway, eventually we did come up into the ground floor; there wasn’t anything going on outside. And Bobby [Robert Helpmann] and Fred and one or two of the boys all decided to go for a walk. She was livid! She thought they were going to be shot down from the sky, you know. And eventually, at night, the following night the two buses arrived, and we went to try to get to the coast. We sat in these two buses, crawling along and we were told, every now and again, not to talk, not to giggle, not to laugh, not to make a sound. And the buses would stop, sort of under a hedge practically, and there was one girl in the company who spoke Dutch. Elizabeth…

Patricia Linton: Not Elizabeth Kennedy?

Pamela May: Kennedy! That’s right. She spoke Dutch and so every time we stopped, she would listen to what the drivers were saying to each other, the front driver would come and talk. They were dropping people, parachutes into the fields the other side of the hedge to where we were. And, of course, we all got the giggles. Anyway, we crawled along and crawled along, and eventually we got to the coast to this huge house in beautiful gardens and we were told we were to stay there for the night: find a bed wherever you can. Find a bed! The place was reeling with people. We went right to the very top, June [Brae] and I, and we found an empty bed. Anyway, as soon as it was light, we all got up and had a walk around, and there were peacocks strutting round the garden, and then all the boys got together and started playing football.

I think it was the next night they suddenly said we’re going to try now. And we all crept, carrying what we could, over a board onto a boat that took cargo, you know. We went down into a hold, and in the corner was a cloth curtain hiding the corner where there were two buckets and that’s all there was. And we slept on straw and when we were on board getting into the ship, they [German aircraft bombers] were going around and round on top of us. We were wondering if we were going to be bombed, but we had to get into the cargo ship. Hope for the best. We got back to London about 3 or 4 o’clock in the morning and everybody’s mother, father, uncle, sisters were all there to meet us and Constant [Lambert, the music director of the Vic-Wells Ballet] had a handkerchief tied over his eye. ‘Oh’, they said, ‘Constant’s been injured!’ It was his cigarette ash had gone in his eye on the boat – the wind. But we’d had nothing to eat and nothing to drink. Margot, June and I got a cup of tea from one of the men who were working the ship, but that was it.

Patricia Linton: But I know you lost a lot of costumes and music and…

Pamela May: Yes. When we left Arnhem, we had to leave everything there. When we got home, of course, Constant had to rewrite a lot of it [the music] was in his own hand. So, he had to rewrite The Rake’s Progress, for instance, but a lot of the music was found by a woman who was an English lover, and she kept it hidden for the whole war and sent it over to Constant when the war finished and he got all his pile of music back. We all thought it had gone for good.

Patricia Linton: Extraordinary!

Pamela May: But I don’t think they could do that with costumes. I think they got lost.

Patricia Linton: So, once you were back, very soon it was the move to the New Theatre. Sadler’s Wells went dark…

Pamela May: Sadler’s Wells was taken over for the homeless, the bombed people to live in. And we went to the New Theatre and Donald Albery, who, his father owned – Bronson Albery – owned the theatre; Donald was the son. He took over managing the company, and he managed us for four years and we used to do a 14-week tour of England, back for four weeks at the New Theatre, then back again, and a tour for 14 weeks, and back again.

Patricia Linton: Extraordinary times.

Pamela May: Quite amazing how much we did.

The transcript of this podcast may have been lightly edited for ease of reading.