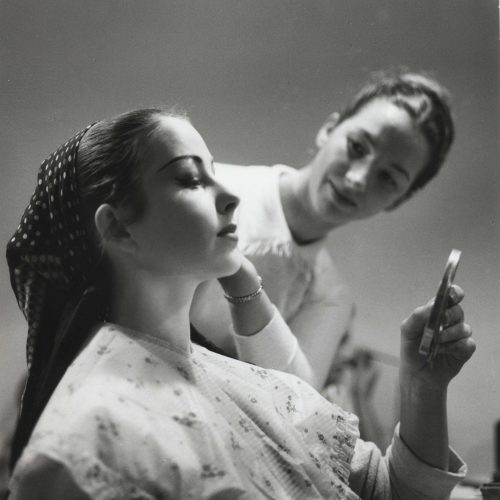

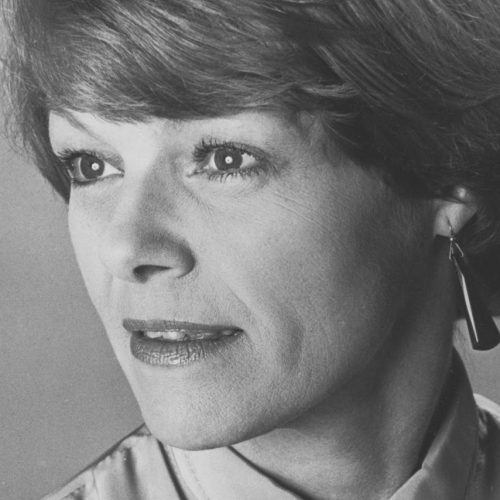

Barbara Fewster

Here Barbara Fewster tells us about working at The Royal Ballet School. Her voice has a mixture of authority and kindness which will be remembered by literally thousands of students over the 40-odd years she both taught and directed there. However, there is also has a tinge of something students rarely noticed, something more searching and pensive, of sadness even. Many dancers, both in The Royal Ballet and in many other companies, owe their careers to her, and remember what she did for them with genuine gratitude. Patricia Linton, founder and director of Voices of British Ballet, feels she owes her own career to Fewster, saying, “She scooped me up from a moment of student gloom when I was about 18 and gave me an opportunity that led to a chance to join The Royal Ballet’. In this interview Barbara Fewster talks to Patricia Linton who also introduces the episode in conversation with Natalie Steed.

First published: September 2, 2025

Biography

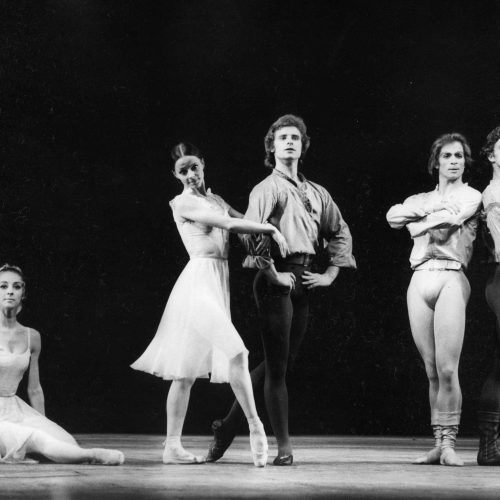

Barbara Fewster was born in 1928. She studied dancing at the Wessex School in Bournemouth before joining the Sadler’s Wells Ballet School in 1942. By 1943, at the height of World War Two, she was performing and touring the country with the Sadler’s Wells Opera Ballet. In 1946 she became a founder member of the Sadler’s Wells Theatre Ballet, a company that became a hot bed of talent for the future of British ballet and a springboard for many and varied careers. There were extensive tours, both at home and abroad, where Fewster was at first a dancer, and then assistant ballet mistress from 1947. When Peggy Van Praagh left the company in 1951, Fewster became the ballet mistress.

Against all the odds of a depressed post-war Britain, ballet was vibrant. The emergence of a swathe of talented choreographers, together with a remarkably varied existing repertoire, helped to build a bright future. On leaving the Sadler’s Wells Theatre Ballet in 1954, Fewster toured the United States of America as ballet mistress with the Old Vic Company’s production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, before joining the staff of the Sadler’s Wells Ballet School, which was now based with the Sadler’s Wells Ballet at Barons Court in West London. She became deputy principal to Ursula Moreton in 1967 and succeeding her as principal in 1968. Fewster joined the Grand Council of both the Imperial Society of Teachers of Dancing (ISTD) and the Royal Academy of Dance (RAD). She was made an Honorary Fellow of the Cecchetti Society by its founder, Cyril Beaumont, in the late 1960s.

Barbara Fewster was an indefatigable traveller and was always inspired by her experiences of teaching and adjudicating worldwide. She was at the heart of an historic cultural exchange with China in the early 1980s, involving an exchange of students and teachers. Fewster was also the driving force of a video for the Cecchetti Society in 1988, to promote and improve good practice in the teaching and understanding of pointework. She has frequently mounted ballets for professional companies, notably Coppélia for the Turkish Ballet in 1993 and a revival of La Fête étrange by Andrée Howard, a ballet close to her heart, for The Royal Ballet in 2003. There is a scholarship in Fewster’s name as part of the Cecchetti Class Ballet Vocational Awards.

Barbara Fewster retired from The Royal Ballet School in 1988, and in the same year was appointed OBE for services to dance. She died in 2024.

Transcript

Barbara Fewster: My time in Sadler’s Wells Theatre Ballet came to an end when I realised that I wasn’t going to do anymore with the company; it was 1954. I had a letter during that time from Ursula Moreton who was the principal, ballet principal of The Royal Ballet School – Sadler’s Wells Ballet School as it was then – saying perhaps I would like to go and see her: she had a proposition to make.

Now, before that as a dancer, I had never thought of teaching. I just wanted to be in the theatre, to dance. I didn’t have an ambition to get to the top, as they put it. I was perfectly happy to be the tallest girl in the back row of the corps de ballet. Loved it.

So, with Ursula Moreton’s suggestion, I went and watched classes for the rest of 1954, and I watched what was now called the graduate class, but in those days, it was called theatre class. I thoroughly enjoyed watching Antoinette Sibley, Lynn Seymour, and a girl called Sylvia Michaels, and they were the – sort of – three stars of the class, and I couldn’t believe my eyes over the standard they reached as students.

And as September came along, I was then asked if I’d like to join the school as a teacher in the Upper School. Learning to teach was not a nightmare, but I didn’t realise what a struggle it was going to be. [Ninette] de Valois [known as Madam] was law, unto not just herself but everybody else. She dictated what we should teach, how we should teach. She used to come in from the company, before she retired from the company, fairly frequently, frighten the life out of all of us teachers.

We had different classes. We had character dancing, we had ‘plastique’, which was one of Madam’s favourite little classes – I had to learn all those interesting movements, which were really taken from the modern contemporary type of dancing movements. The exercises I had to learn from one of the teachers in the school called Margaret Graham, who had learnt them from de Valois herself. I also taught – learnt to teach – mime. Ursula Moreton, being a wonderful mime exponent herself, and teacher of mime. And Ailne Phillips was teaching at that time, and her classes were absolutely, wonderful. Her work was again based on Cecchetti work [the Cecchetti Method of Enrico Cecchetti], as were Madam’s memories, and Ursula Moreton was also, at times, in Cecchetti’s classes himself.

So, we had a kind of legacy of the Italian teacher’s work, although there was no strict syllabus. During ten years, which was before I went to the school, de Valois invented a summer school for teachers. There was a course on pointe work, there was a course on pirouettes, there was a course on port de bras. Each year, these subjects varied. There was a course on mime.

There were five leading schools in England at that time when I joined the school, and all those principals came to London in the summer for a two-week summer course that de Valois ran. And out of that, the teaching became much more generalised, the standard of teaching throughout the country.

So, in a way, although people used to ask me time and again, ‘Do you have a syllabus?’ it evolved from Madam’s experience. She danced with [Edouard] Espinosa. She danced with [Nicholas] Legat, she danced with – not danced with, but studied with – Cecchetti, and out of those, she believed a lot of each of those gentlemen’s, systems, but having a very open mind and an exploring mind, and an analytical mind, she always broke away from the standard exercises that were given, and formed her own. She always said, ‘I was a bad pupil of Cecchetti’s’, she said to me, because she said, ‘I was always turning his exercises round and doing something else with them.’ In other words, choreographing.

Because we had all these things through our training, we really followed the route that we had already been used to. So, in a way, it was like a family recipe. And as I have said, Dame Ninette used to come into the school frequently, and if something was going wrong, she corrected it very quickly. She always used to say a lot about [Fredreick] Ashton’s ballets, and through his creative work a style evolved, which sort of put the cap on the ‘English’ dancing style. Ashton used to say, ‘The school teaches technique, it’s up to the company to teach the art of the dance.’

The ‘English’ style was based a great deal on the French influence of footwork, and quick footwork, and [was] varied. If you went this way, you went that way, the other way the next minute, sort of thing, or the next second. Whatever you did coming forwards, you always had the reverse going backwards. The music, she used to vary. Therefore, I think we’re talking about versatility. Dancers being very versatile. Anything she gave, let’s say a collection of steps that were to a slow sort of movement, musically, she would then double the speed, and ask the pianist to play something else, and you had to fit that mixture of steps into that time and music.

Patricia Linton: A choreographic element in it?

Barbara Fewster: Choreographic element, but quick thinking, quick speed, very sharp. I always think English dancers have a sort of, an open base of very adaptable movements that can take on any other demand. In other words, we can – we can become – we can take on, we don’t always excel in it, we can take on the American style, Balanchine. We can take on a French number of Roland Petit. We can take on all these different styles of dancing from other places, or from other choreographers without too much difficulty.

At the same time, I think what has been lacking is the open, free, oriental movements that the Russians bring in. I tried to bring in Russian teaching at one stage for the boys. And I employed a young man who had had a lot of Russian training, Piers Beaumont, who I felt his work was exciting, strengthening, very good for the boys. Really opening up their movements and giving them much more information on how to jump, and leap, and spin, and I thought for the short time we had him, that he did a lot of good. Stephen Beagley was one of his [students]. But he [Beaumont] wasn’t allowed to stay. I wasn’t allowed to keep that ‘Russian’ training, as it was referred to.

The boys seemed to me to be well behind the girls in standard. I think, at the time when Kenneth MacMillan took over the company, he was very critical of the standard of work of the boys in the school, and that, well, that caused me to take in this young man, and also to have some physical, some weight lifting exercises brought in for the boys, to try and build their physique. Because I think it was all bits of ideas I had, that I wasn’t able to pull together.

Patricia Linton: So, you did have a vision?

Barbara Fewster: I had a vision, but I didn’t know how I was going to achieve it. I did bring in contemporary dance to the Upper School at The Royal Ballet. Much against de Valois’ wishes, much against. I was fought heavily on that one.

Patricia Linton: Why? Why was she against?

Barbara Fewster: Ballet was ballet, as far as she was concerned, and it could absorb into itself what it wanted, but not to bring in special classes for contemporary dance. She was quite adamant on that.

Patricia Linton: But you won?

Barbara Fewster: Yes, thank goodness, because I could see in the modern age, my views were that if our students were going to go to other companies to dance, they would find themselves faced with movements that came out of, were born from the contemporary work, which they wouldn’t be able to cope with. They wouldn’t know how to copy. That was a very distinct time when Robert Cohan opened his school at The Place, and was showing London what, you know, this [contemporary dance] could be, how this could be enriching for all dancers.

When I retired from the school, I felt spent. I felt as if I had given it as much as I possibly could, and I did not see how I could – I really could not see how I could take it further. It looked like a state of repetition to me, of what we had done and achieved, but it was going round in a circle. I could see the weaknesses, but I didn’t personally feel – I felt it was for someone else to take it further.

But the whole of my time in the school [it] was totally dictated to by Madam. Totally. But one was so privileged to work in the organisation at all and she gave me life and, you know, you have to take the rough with the smooth.

The transcript of this podcast may have been lightly edited for ease of reading.