Anita Landa

From a start in Flamenco, Greek dancing and a bit of ballet, Anita Landa describes here not only how her dancing life took off, but how Festival Ballet started. The Cone Ripman School, Alicia Markova, Anton Dolin, a healthy injection of glamorous Diaghilev stars and repertoire all get proper credit. However, the lion’s share of the company’s success, she says, was down to the indefatigable impresario Julian Braunsweg. ‘Without him there would be no English National Ballet!’ In this interview Anita Landa talks to Patricia Linton, and it is introduced by the dance writer and critic Deborah Weiss who is a former senior soloist with London Festival Ballet.

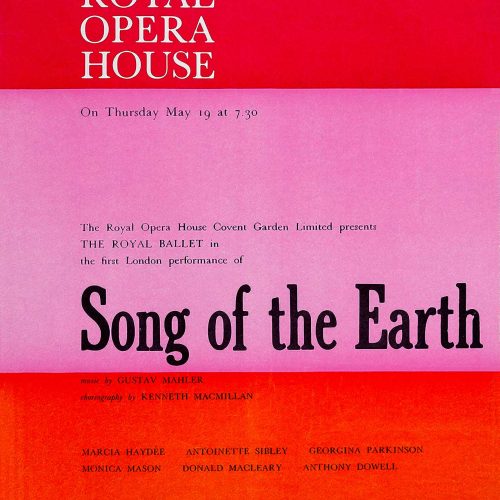

First published: August 26, 2025

Biography

Anita Landa must have been vivacious from birth! Her dancing life has been refreshingly varied. Born in Las Arenas in Spain in 1929, she moved to the UK just before World War Two, but the Spanish part of her character and her early life was to prove an important catalyst and influence on her future. After four years studying a variety of dance styles at the Ginner-Mawer School, Landa spent some time at the Sadler’s Wells Ballet School whilst simultaneously continuing her Spanish dancing studies with Elsa Brunelleschi. Her next and fortuitous move was to the Cone-Ripman School. From here she succeeded in an audition for the newly formed Markova-Dolin Ballet in 1949. The company soon took root and became known in 1950 as Festival Ballet.

The company’s very distinct international outlook suited Landa. She revelled in the life, absorbing much from the galaxy of star dancers and the extensive repertoire. She became a principal and danced until 1960 when, married to fellow dancer, Michael Hogan and expecting their first of three children, she retired. However, after eight years she returned to the ballet world. Her broad dance background and natural intelligence and sparkle made her an ideal choice for the intricate role of ballet mistress. After working with Northern Ballet Theatre and on various Nureyev Festivals, she joined the staff of the Sadler’s Wells Royal Ballet in 1979. She remained with the company as ballet mistress and character dancer until 1995, including the company’s move to Birmingham in 1990, when Sadler’s Wells Royal Ballet became Birmingham Royal Ballet. A wealth of work and activity and acclaim was achieved over these 16 years, until Anita handed the baton over to Marion Tait. She continued to be involved in ballet related activities, including being a member of the National Council for Dance Education and Training for several years. Hugely knowledgeable and exuberant, she is a bonus at any gathering.

Transcript

in conversation with Patricia Linton

Anita Landa: I was in a school that had a lovely lady called Nancy Sherwood, who did Greek – the Ruby Ginner Greek dance – and I did one class a week with her. She saw that I could dance, so she asked Ruby Ginner to come and watch me one day at the school. Ruby Ginner came along, said, ‘We have a school in Boscastle, and we do education as well.’ So, she wrote to my father in the West Indies, and my father said, ‘I will go for it.’ So, I moved to Ginner-Mawer, and I did four years of Ginner-Mawer Greek dance. It was a Ginner-Mawer school, and they did marvellous mime, acting, speech, Greek dance, and national, and no ballet, and I got all the exams, and I got to about the age of 16, and I said to Miss Ginner one day, ‘But I want to do ballet.’ She said, ‘My dear, we will take you to London, and you can do an audition, and we will sort you out.’ So, she put me in an audition with [was it the] Sadler’s Wells Ballet then?

Patricia Linton: Yes, Sadler’s Wells Ballet School.

AL: I got in, I scraped in. How, I have no idea, but I got in there for about six months, but she also put me with Elsa Brunelleschi who did the wonderful Spanish school in West Bromsgrove. Beryl Grey used to go in there as well, so I remember her very well, doing her Spanish, and I did very well with the Spanish. My ballet wasn’t so hot, and it was so funny because when I met Haskell later on in life, I said, ‘You know I went to your school,’ he said, ‘Yes, yes, I know all about you, we told you you would never be a dancer,’ and I said, ‘Yes you did.’

PL: This is Arnold Haskell.

AL: I was 16. The school said, ‘Look, go [and] do character work, go [and] do Spanish.’ I was good at Flamenco. So I went, and I had a friend who was teaching mime at the Arts [Educational School], and she said, ‘Join the Arts, I’ll get you into the Arts.’ (They were the Cone-Ripman [School] in those days, [it] wasn’t the Arts Educational it was the Cone-Ripman School.) ‘You will do your Cecchetti exams,’ and I did my Cecchetti exams. I did my Elementary and my Intermediate within a year, and I did a show at the Savoy [Theatre] with Julian Braunsweg’s Ana Esmeralda company. I did Flamenco there for one season, and I stayed at the Arts, and that’s how my dancing started. Flamenco, Greek dance, and a bit of ballet.

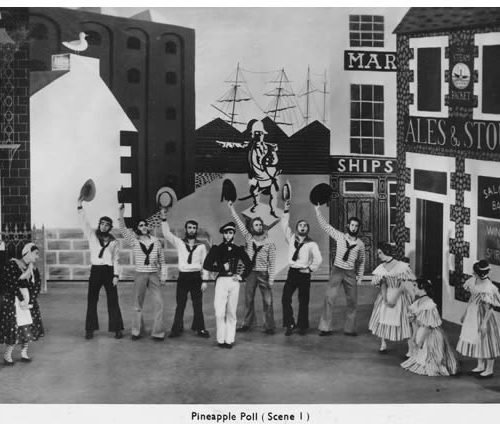

PL: So well, the late 1940s, and you have gone to the Cone-Ripman School, which must have been very good, because I read somewhere that the corps de ballet, when you finally made this group with Markova and Dolin, were excellent.

AL: They were wonderful, and they were all different shapes and sizes, you have never seen such different people.

PL: So, what was the magic?

AL: It was the magic of having this lady who knew what she wanted. She wasn’t worried that one girl had bigger bosoms than the next, or anything like that, they had to have a style, and a feel of it, and all of a sudden, we had all these girls of different shapes, gone into a line in [the] Wilis [in Giselle], and they looked spectacular, and they were wonderful.

PL: When you said, ‘this woman’, there is a photograph here – it’s Markova.

AL: Markova. She gave me that on the concert tour. When she was 40.

PL: And how much influence did she have on the Cone-Ripman school?

AL: I think a lot.

PL: They must have done a good job to have got you all to the point where Markova was going to gather you up and…

AL: Absolutely. Well, Grace Cone came to us one morning and said, ‘Tomorrow morning girls and boys, you are going to an audition.’ And suddenly this wonderful lady comes in, with a fur coat and earrings, and beautiful hair, and high heels. She had these wonderful high heels with sort of straps going up. We all stood in amazement, then [Anton] Dolin came in, and then Braunsweg came in, and I saw Braunsweg, and he saw me, and he remembers me from the Ana Esmeralda company. This lady had such a fantastic feel for us, and we had such a fantastic feel for her, and she went, ‘I’ll have you, and you, and you, and you, and you, and you, and you,’ and in about 20 minutes she had picked all the girls, except me. She didn’t pick me, but she had an idea that she wanted to do some Spanish work in the concert tour, and Braunsweg said, ‘Anita can do castanets, Spanish,’ and she said, ‘You are in.’ So, I got in for that, and I was the 13th girl, and I was the understudy although I was in everything, and we did the tour.

PL: Is there anything you would like to say about Grace Cone at all?

AL: Oh, she was very strict. You know, everybody had to look immaculate. You know, you had to be polite. There was the most incredible thing, when we all got our letter to say we had got into the Markova tour, she said, ‘Now girls, and boys,’ because two boys got in, Malcolm Goddard and Louis Godfrey. She took us into the room, and she said, ‘Now, if you saw the Queen of England, you would curtsey, wouldn’t you?’ She said to the girls, and we said, ‘Oh yes, of course we would.’ She said, ‘Well,’ she said, ‘Markova,’ she was Madam then, ‘Madam Markova is the queen of ballet, and I would like you all to curtsey when you see her,’ and we did. The foundation of Festival Ballet was all Gracie Cone dancers, you see.

PL: So, how did you realise what Markova and Dolin were doing? Did you realise they were trying to form a company?

AL: No, we just thought it was a small contract, and we were just thrilled to bits, and we rehearsed for about three weeks, and we did this phenomenal tour, which was such a success for Markova and Dolin. I think the War had just finished, and we were still on ration books, there was very little food. We went to the theatre, and it was magic, and the audiences were phenomenal. So, we thought at the end of that, Braunsweg said, ‘Thank you very much, girls, and the two boys, we will be in touch,’ kind of thing. I think that Markova and Dolin, they had a very famous impresario in America. No, they had an agent called Alfred Katz, and he was going to take them back to America. They had lots of work in America, Markova and Dolin, but Braunsweg and Dolin – I think also Dolin wanted to have a company in this country, but Markova didn’t, no, she maybe wanted to go to Hollywood. So, I think it was Braunsweg [who] asked them. He said to them, ‘I can get some more dancers, why don’t we go to small theatres? We have got something here.’

I mean, looking back, we didn’t have much scenery, the costumes were all made in five minutes. We coped. We bought our own flowers to put here.

PL: And it was the right time, as you say. The public really needed something to cheer them up, to take their mind off the gloom [talking over each other].

AL: They loved it, and we went to – and there was always people at the stage door raving for Markova and Dolin, ‘Markova and Dolin, Markova and Dolin,’ you see. But the background was all our little dancers, all our little girls who were doing bits and pieces, you see. Noel did a lot, because Markova was ill [for] part of that tour, and Noel Rossana took over from Markova. Imagine that girl from school, she was only about 18.

PL: How much did you get paid, do you remember?

AL: Well, this tour, the Concert Tour was £7. I think when we went onto bigger theatres, which was in 1950, I think I got up to £8, and out of that we paid [for] our food, our digs, our tights, our make-up. Not our shoes, and not our travelling, but everything else, out of this £7, and I saved.

PL: What happened then?

AL: What happened then? We all went back to school. I went to Birmingham to do a pantomime at the Birmingham Rep, which was the old Birmingham Rep[ertory Theatre], and we earned a bit of money. Then, when we got back, I think – by that time Braunsweg had encouraged Markova and Dolin, or at least encouraged Markova, that it would be a wonderful idea if they stayed, and that he could push it into a bigger company. I think he asked about another 20, 25 dancers. He did it like that, he just suddenly found all these dancers, and it gelled. I mean, he got John Gilpin, brilliant. Beautiful, John Gilpin, he was 19 or 20. And he got [Vassilie] Trunoff later, and [Nathalie] Krassovska came, and there we were in 1950 with a sort of ready-made small company.

PL: And it was the energy of Dolin, you think, that made this gel?

AL: Yes, and Braunsweg. Well, Braunsweg was a wonderful impresario. If he wasn’t going to get this company going, he was going to do an Indian company, or an orchestra from Poland. He wasn’t going to hang around. And then Markova said, ‘No, no, I am going back to America, there will be no English National Ballet.’ There wouldn’t be.

I remember her inviting us to the hotel in Liverpool, where she was staying at her suite, and she asked all of us to have a meal with her, and we said, ‘Yes please.’ We went from these terrible digs one night to have dinner with her, and she thought – you know, she loved us, she was lovely with us, and she gave us – well she gave me that beautiful photograph, and she was…

PL: Did you mind this sort of gap of being [talking over each other].

AL: Oh, huge gap.

PL: Between such affluence and poverty? Did it bother you?

AL: It didn’t bother us at all, because we knew she was the star, and we were just the corps [de ballet]. And there was the most enormous difference in those days, between the star and the corps, which doesn’t happen anymore, and I am glad I had a star like that to look up to.

PL: Did she take an interest in all you girls?

AL: Oh, yes. Oh, yes, she did.

PL: Did she realise she needed to develop your individual qualities?

AL: Yes, she did, and I think Dolin did. I think what was amazing about Dolin, he was – he had this – he allowed you a freedom of expression, up to a certain point. There would come a time when he said, ‘Look, I think you are overdoing that bit now, we will calm it down.’ You know, he would do that, but, on the whole, he would allow all these unknown little kids that we were, from the Cone-Ripman, to develop into very nice artists for his company.

PL: How much do you think they both might have been influenced from the very exotic Diaghilev [Ballets Russes]?

AL: Oh, absolutely. Absolutely. I think we were the link with this kind of work, especially when we went to the Stoll Theatre. We were the link between the Diaghilev and the Russian, the Ballet Russe – we had all the Ballet Russe dancers in our first season at the Stoll. So, we watched them perform, and grab[bed] what we could from them, and then we went to build our own company, which was called London Festival Ballet. But they always came in and gave us a marvellous impression of what Ballet Russe must have been like, the theatricality and the dramas and everything, and it did seep into us a little bit. We had [Tatiana] Riabouchinska, [Alexandra] Danilova, David Lichine, [Léonide] Massine and [Mia] Slavenska. Massine wanted to shout in Russian at me, as he did in Beau Danube, he was allowed to do that, and that was how he was going to be. Danilova would pass us and say, ‘Don’t you touch my tutu,’ so we wouldn’t touch her tutu, and we thought, ‘These are gods.’ They were gods, you know, to us. We learned a lot. They had their own personalities, their own way of performing, and of course they spoke Russian all the time backstage. The Firm. They were like – yes, they were a firm.

What Dolin would do is every night – we did ten weeks at the Festival Hall, with triple bills, and we packed it. Most of it was triple bills, and we packed it, but every night he would come through those curtains, while they were still clapping, and say, ‘Ladies and gentlemen, thank you so much for your support, we love you coming here, we have a great company, please come and support us,’ and do you know? Those people would come back, and back, and back, for ten weeks, and every night he would give a speech. That’s the way we grasped our audiences.

PL: In a way that’s the way the Diaghilev company worked, with the triple bills.

AL: Absolutely.

PL: The three different ballets, isn’t it?

AL: Yes, oh yes. They had triple bills, and only triple bills.

PL: Isn’t it interesting, because nowadays it’s so much easier to sell a full-length ballet?

AL: Yes, but you see people liked that. The triple bills we did, they liked. We would finish with Symphony for Fun, or we had Beau Danube, or we would have a very good Petrushka in the middle, or Scheherazade, and Les Sylphides with Markova, or a guest artist. We had a lot of guest artists. I think without the guest artists, it would have been very difficult. They were big stars. They were famous, they were Diaghilev, they were glamorous, they were so glamorous.

PL: Even in these very straightened times, they appeared looking a million dollars.

AL: Oh, Danilova! And Toumanova, I mean she was a film star, you know, fur coats and high heels. ‘Oh, my darling, my darling.’ Doushka [Toumanova] was wonderful, they were wonderful. They were wonderful. No, they were stars, they were stars, and they remained stars till they all died.

I am just so privileged I did all those wonderful years when we danced. We just wanted to dance, and we danced and the public – you see, if the public hadn’t been there, we wouldn’t have had careers, and there wouldn’t have been a Festival Ballet. So, we must have done something right that the public came to see those few years of Festival, 18 years that Braunsweg was there.

The transcript of this podcast may have been lightly edited for ease of reading.