John Craxton

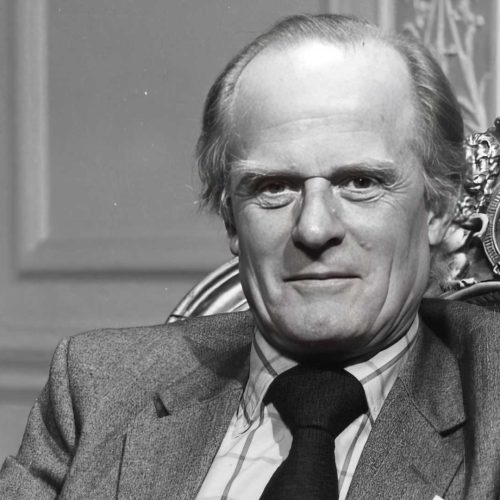

For over half a century, John Craxton was a major force in the visual arts of this country. From the late 1940s on, his main source of inspiration had been the landscape and people of Greece. Choosing Craxton for the designs, sets and costumes of Frederick Ashton’s Daphnis and Chloë in 1951 was, therefore, an inspired choice. In conversation with Patricia Linton and Anthony O’Hear, Craxton speaks of how this came about, of working with Ashton, and of the influence of Margot Fonteyn on his work. He also expresses strong views on the importance of visual artists in ballet.

The epsiode is introduced by Anthony O’ Hear, who talks to Natalie Steed.

First published: April 15, 2025

Biography

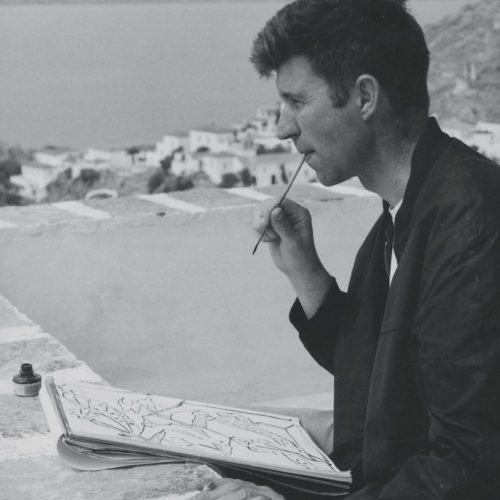

John Craxton was born in London in 1922 into a well-known musical family. His father, Harold Craxton, was a composer and, for over 40 years, a Professor at the Royal Academy of Music. Janet Craxton, John’s sister, was a distinguished oboeist. At the age of 17, John Craxton went to Paris to study art, being too young for the Chelsea School of Art. When war started, he continued his studies in various London colleges. He mounted solo exhibitions in 1942 and 1944 and in 1943 toured Pembrokeshire with his contemporary Graham Sutherland, by whom he was clearly influenced. Other influences around this time were the Romantic painter Samuel Palmer (1805 – 1881) and his close friend Lucian Freud.

After the war Craxton began to travel widely, but it was Greece, and Crete specifically, that particularly attracted him and where he spent increasing amounts of time. From around 1970 until his death in 2009, he shared his life between a home in Crete and London.

Craxton was attracted to the light and colour of Greece, and to what he saw as an arcadian life, both human and natural. His art became suffused with the textures, personalities and the floral and geological forms of Greece, all rendered with striking clarity and colour. As time went on, his often very large canvases showed a tendency to semi-abstraction, but an abstraction always rooted in the flowers, trees, landscapes and pastoral life of Greece, and at times showing the influence of Byzantine iconography.

His designs for the ballet Daphnis and Chlöe in 1951 are at the start of his Grecian odyssey, and show clearly the direction his art was taking, away from England and Wales, and into an imagined Hellenic paradise.

Over the years Craxton gained increasing recognition, both in Britain and in his adopted Greece. He had major retrospectives at the Whitechapel Gallery in 1967 and, two years after his death, at Tate Britain in 2011. John Craxton was elected Royal Academician in 1993.

Transcript

In conversation with Patricia Linton and Anthony O'Hear

John Craxton: It’s an instinctive thing you either have or you haven’t got; it’s like being a dancer, you know, you suddenly want to dance. I just wanted to paint. I know that from a very early age I wanted to be a painter. People said, you know, “Young man, you know, what are you going to be when you grow up?” and I’d say, “I want to be a painter”, and they said, “Well that’s going to be a very hard life.” Everybody told me it’s going to be a very hard life and, well, it hasn’t been easy, I have to say, but it’s been a wonderful life, and I’ve really enjoyed being a painter.

Patricia Linton: How did you get involved in ballet?

John Craxton: I’d been to the ballet, and I loved the whole idea of the ballet. We went to preparatory school in a place called Betteshanger in Kent, and one of the boys was called Oliver and he had, before he’d come to school, been doing basic ballet exercises. The mother said I want my son to continue his ballet classes, so somebody was sent down from London twice a week to take us through our ballet exercises, which we then did every morning. And the man in question was called [Harcourt] Algeranoff. I think he’d been a character dancer with the De Basil [Wassily De Basil’s Ballets Russes] and he certainly played the magician in the Petrushka. I was staying with the Olivers, and young Robin Oliver, in Scotland, and downstairs in their little playroom was a gramophone. I found a record that had Petrushka written on it. I put this record on, and I couldn’t be taken away from it. I said this is the most marvellous music I’ve ever heard in my life, this is exactly what I want to listen to.

Anyway, I left Scotland, went down south to Selsey Bill, where we had a bungalow, and I was looking at The Times one day and everything was on the front page then, all the theatres and cinemas, and I saw this name at the top – Petrushka – you see, and I said, ‘Is this the same thing as what I was listening to in Scotland?’ And he said, ‘Yes, Petrushka is a ballet by [Igor] Stravinsky’. So my parents said, ‘Look, we’ll go up to London early today by car, and we’ll go to Covent Garden and we’ll get seats’. I have never enjoyed myself so much. There was Petrushka, there were dances for the end of Sleeping Beauty, you know, Aurora’s Wedding it was called.

Patricia Linton: So this must have been the [Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes]?

John Craxton: Yes, Ballets Russes. The whole thing was a miracle to me because, first of all, it was one of the most brilliant ballets ever created, because ballet dancers are like puppets in a way, they can play at being natural, so in this ballet they started with playing at being natural and then the curtains draw and you see the puppets, and then the Magician brings them to life. So you have this double thing going the whole time. You enter into the theatre and see reality, and then you see unreality. And then what happens is Petrushka turns out to be human. The whole thing is so wonderfully complex, almost like three or four dimensions you’re going to.

Anthony O’Hear: Were you interested at all in the sets?

John Craxton: Yes, I have to say, this is very, very important what I’m going to say, is that I gave a lecture at the Diaghilev exhibition and the point of my lecture was that Diaghilev was so important because he took painters, artists, to do his sets for him, to do the designs. He did not employ decorators, and the reason is that because painters bring with them to the theatre ideas, visual ideas, which designers and decorators don’t have, they’re usually second-hand, the design ideas. It’s not powerful, and all the good sets that have ever been done were the result of the fusion between the artist and the composer and the choreographer. The dancer is vitally important, but the dancer is actually doing what the choreographer asks him to do. That’s what’s so extraordinarily difficult about ballet. It’s such a dodgy art form; if one element is faulty there then the whole thing goes a bit crumbly, you know. But when you get a fusion of the best dancers, the best scenery, the best music, the best choreography, it’s one of the most magical things you can get. And it’s so wonderful because it’s ephemeral, that’s what I find so exciting about it.

So when I got the job to do Daphnis and Chlöe I thought, one should definitely do really what one wanted, and the reason why I was chosen was because Freddy [Ashton] wanted somebody who’d been to Greece. I think he talked with Kenneth Clark about it, who suggested a painter who was totally unsuitable who was a girlfriend of his, and Fred said – Fred was very strong-willed when he wanted to be you know – and he said, ‘No, I want it to be somebody who knows Greece’.

So I got a telegram in Poros, I was busy painting a huge painting for the 1951 Exhibition and I didn’t want to leave it and I was in the same house as Patrick Leigh Fermor, who was writing a book; it was a lovely set-up and I was very happy, and it was in the autumn of 1950. [The] telegram said, ‘Will you telephone please Freddy Ashton, with a view to possibly designing the ballet Daphnis and Chlöe’. And so it meant getting on a boat and going to Athens, and telephoning him from the embassy. So I got him on the phone and said, ‘Fred how are you?’ and he said, ‘Not too well I’ve got flu’. I said ‘What’s the position of this ballet?’ He said, ‘Well, was wondering whether you could come and we could discuss it’. So I said ‘There’s nothing settled?’ ‘No, I haven’t settled anything yet.’ And I said ‘Oh’. And I said, ‘Fred, what’s the possibility of doing it in contemporary Greek costume, as though it’s Greece today?’ He said, ‘I’m quite prepared to discuss it, sounds interesting, but I can’t give you a yes or no’.

So I was totally depressed and left the embassy and went up the road in Athens and went to see a friend of mine, who was ill in bed also. I said, ‘I don’t know what to do, what to decide. What do I do? Do I go to London and risk it, give up my work here?’ I went and sat down in a darkened room and I turned the radio on and, blow me down, they were playing Daphnis and Chlöe. So I said, ‘Right, it’s made up for me’. I went back to the embassy and said, ‘I’m going to London’, so they said ‘We’ll arrange a plane for you’, so I went back to Poros, rolled my pictures up in a big roll, brought them back to Athens, got on a plane, arrived in London, found Fred still ill in bed. He said, ‘What’s it like in Greece?’, I said. ‘Wonderful’. I’d brought with me paintings of Greek dancers and things, you know, and drawings, and he said, ‘How do they dance?’ So I said, ‘They dance so wide, I love the way they hit the ankles like that when they dance, and they hold arms’, and I showed him the painting of people holding their shoulders, yes, all that sort of thing. So without him saying yes or no, it was sort of, I said ‘I’ll go away and do some designs’. ‘Could you do that?’ There was no yes or no, it was not decided, there was no contract, nothing was done.

From the very beginning Fred and I just decided on the layout of the ballet – we decided on how it was going to be. I said, ‘It’s got to be Pan’. He said, ‘Well Pan, in the original thing, Pan is a rock which moves’. I said, ‘I don’t like that idea, Fred, at all. We’ve got to have – can we have Pan?’ He said, ‘Yes, you can have Pan if you want’. I said, ‘It’s much better to have Pan as a person, rather than have a rock that moves that looks like him’. I said, ‘Fred, can we have Pan coming out of the floor?’ ‘Yes, of course.’ Oh yes, another thing, in the original ballet there are only two scenes, and I said, ‘Fred, you can’t have two scenes; you can’t go back to the first scene after the second scene; it’s not visually good. Can’t we have?’ and I knew his Symphonic Variations, so I said, ‘Can’t we have the last scene completely bare stage by the sea, so you can do a kind of Freddie Ashton Symphonic Variations with nothing to get in the way’. And he was pleased about that. So we put in an extra scene, which wasn’t in the book, so, of course, there’s a terrible problem because there’s no music between the two scenes. Between the second and last scene there’s no music. That was a big problem.

Anthony O’Hear: So what happened?

John Craxton: Well, the last movement of Daphnis and Chlöe is played at the beginning of that, and then the curtain goes up. Doesn’t matter. But there was a kind of collaboration which went on between us – I said, ‘I want the colour thing to be important, I want chords of colour, so the dresses should be different shades of colours in order to form different chords as the people move across and join up, so you get different …’ – and then I wanted Chlöe to be in yellow, I thought Chlöe should be innocent, spring-like, yellow, completely unique. There were no other yellows in the whole stage. And, of course, on the dress rehearsal, terrible moment, she [Margot Fonteyn] said, ‘I’m not going to wear this, it looks quite grey’. The lighting was so feeble in 1951, do you know, it was very primitive, was only lighting really for the opera. So there was no lighting that lit up a yellow dress and she said I want the pink one. So she put on the pink dress.

I have to say the truth now, let it be said, that I’ve never been able to light Daphnis and Chlöe the way I wanted it to be. I wanted to use lighting more like a brush. In fact the scenery is designed to be lit and to be made into shadows and then lit up and then disappear, so I wasn’t getting my way. But that’s one of the things I didn’t succeed in doing.

There were times when a lot of the scenery was just thrown away during the production, and in the last scene trees were missing, and I said, ‘where are those trees?’ and they said, ‘Oh it didn’t have any trees there’, and I said, ‘Yes it did, there were fig trees in between the olive trees.’ ‘No, there aren’t any.’ ‘Yes, there are, I designed them.’ ‘You say there are, but I don’t remember any’.

We thought we were going to get debagged. I got a telegram saying we were going to be debagged tonight, the critics are all against it. There were some wonderfully nasty reviews. The Daily Express – Margot dances in her undies, is this what the Royal Ballet has come to, is this what we pay our taxes to see?

Patricia Linton: When you started designing it, had Ashton already said who he was thinking of using as Daphnis and Chlöe, and did this influence you in any way?

John Craxton: Yes. I met Margot very soon because I’d designed a dress, a very simple dress which you see now on the stage, and there was a woman there in charge of the costume department and I was a complete novice – I was absolutely out of my depth. So she got hold of my design and she started doing all these little cross things across the shoulders, puckered 1938 cocktail dress, and we went to have a fitting with Margot and Fred and I was absolutely quivering with horror. I said, ‘It’s not really what I…’, so Margot then said, ‘I know what John wants’. So she set to work and she designed the first dress – the basic dress which she wore – and we made it out of stockinette. The whole time she was backing me up – she was wonderful.

At the time that I knew her, 1951, she was getting 30 quid a week. And she had £200 in the bank, and she had a mink coat which she had not declared had been given her. It was a cause of great worry for her because she finally decided, we decided, you’ve got to go over to France next time and take the mink coat with you and then come back and declare it as second hand or something. But it was a real problem. She was struggling and people used to send her food from, Roy Browning used to send pies from the Savoy Hotel. She was always able to be the guest of people, and people helped her, but she didn’t have financial backing at all of [from] a rich family or a rich husband. Above all she [Fonteyn] was a great artist. And instead of going off and getting a job in America, which she probably could have done, she stood by the company, accepting this mean little handout. And that was Mr [David] Webster; he was only interested in the opera. Mr Webster was away the whole time I was working on Daphnis, scouring the world looking for opera singers, so when he came back he said, ‘Oh John, we haven’t discussed contracts’, two days before the first night. ‘We haven’t had a contract, we haven’t decided about what we’re going to pay you.’ I said, ‘We’ll decide on something, don’t worry.’ He said, ‘Well come and see me tomorrow morning at 10 o’clock.’ I was in a real state – what am I going to do, as everybody told me he’ll beat you down. So I rang K [Ken] Clark and said, ‘What am I going to do?’ He said, ‘Set your price at £500’. So he said, ‘I’m prepared to offer you £300 for the whole ballet’. I said, ‘There were 3 scenes and 54 costumes do you know, 3 scenes of scenery, £300 – a hundred quid, one scene, that’s a bit little’. He said, ‘Well, you know, that’s what we normally pay’. So he then said, ‘Well what is your price?’ and I said, ‘500’, and he said, ‘Oh’, he said, ‘You’ve got me, you’ve got me by the balls’. I said, ‘No I haven’t, Mr Webster, you know I would never dare to touch your balls [laughs], I wouldn’t want to and I wouldn’t dare to’. I said, ‘It’s just that’s my price’. So he gave me a cheque for 500, which was lovely. So I proceeded to blow it on Margot and myself – we had a wonderful time.

The transcript of this podcast may have been lightly edited for ease of reading.