Noel Bronley

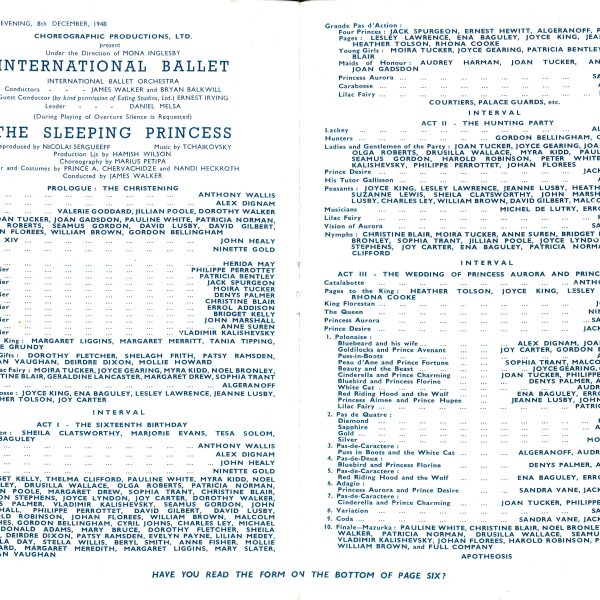

Noel Bronley was a member of International Ballet from 1946 until it closed in 1953. Little remembered now, at the time International Ballet was a very large undertaking of over 100 people. It toured extensively, both in Britain and abroad, under the direction of its founder, director and prima ballerina, the redoubtable Mona Inglesby. In conversation with Patricia Linton, Noel speaks about the vicissitudes of touring and landladies, and also gives us some candid insights into the character of Mona Inglesby – and the Inglesby parents.

First published: April 22, 2025

Biography

Born on Christmas Day in 1927, Noel Bronley (born Brown) started ballet classes in order to strengthen her body and correct a curvature of the spine. Loving dancing, she quickly became determined to have a life in ballet and trained at the Sadler’s Wells Ballet School, although, as a security, her father insisted that she did a Pitman’s course in shorthand and typing. She joined Mona Inglesby’s International Ballet in 1946, when it had been running for 5 years. Having joined, and, at Inglesby’s insistence, having adopted the name Bronley (after Bronislava Nijinska), Noel immersed herself in touring and performing in what at the time was a bigger company than the Sadler’s Wells Ballet. This was her life until 1953, when, having failed to secure an Arts Council grant, International Ballet was forced to fold, despite having brought ballet to millions over its existence and up to then having had no public funding. Since 1953 Noel has played a big role in keeping memories of the company alive and ex-members in touch through re-unions. Belated recognition of International Ballet came when a plaque was placed in the Royal Festival Hall on London’s South Bank in 2012.

Transcript

In conversation with Patricia Linton

Noel Bronley: When I went into the International Ballet I was 18, and I went into the company in January 1946. I can remember standing beside the mantelpiece at our home with this contract and my father said to me, ‘Now, are you absolutely sure this is what you want to do?’ and I thought, ‘No, it isn’t,’ but we’d gone too far now, so that was that. Also, I wouldn’t have had a clue what else to do if I didn’t do that, and, I mean, I could never have done that to my mother. She had scrimped and scraped for all those years, gone without things.

Patricia Linton: So you felt duty bound?

Noel Bronley: Oh absolutely, yes. There was absolutely no question about it but then, you see, I’d no conceptions at all of what it would be like to be in a company. What it would be like to go out on tour with people. Share beds, I mean they might just as well have said to me, ‘Would you like to live on Mars?’ because I’d no more knowledge of it, really

Patricia Linton: Was it big, the company at this time?

Noel Bronley: Yes, this is what I’m always telling people. It was bigger than Sadler’s Wells, and the orchestra was bigger. It, it was enormous. I think, at its biggest, there was probably nearly 100 people touring, with the electricians and things like that. And, and the wardrobe. It was big. Particularly because we did so much touring, there was this family feeling, which you get because you’re on train calls together, you’re in digs together.

Patricia Linton: How did you find your digs?

Noel Bronley: That’s fascinating. Equity published a little blue book. It contained the addresses of landladies, and you would chat to people and say, ‘Have you been to Mrs Gray’s? Is she any good?’ ‘Yes, she’s lovely, but you’ve got to write quickly to get in.’ And the drill was, as soon as the tour list went up, you wrote to the landladies of your choice in each town. First of all, you’d usually find somebody to dig with. And because I’d known Grace Greenway in the Wells School, I asked her if I could dig with her. And she said yes, which was very sweet, because she was quite a bit older than me. So I was so helped along by that. I mean, if I’d had to go in cold, I don’t know what I would have done. So you wrote to your landlady, enclosing a stamped addressed envelope, and she wrote back and told you if she was available or not. When you were on tour, as soon as the train call for the Sunday went up, on the Saturday, you went out to the Post Office and you wrote out your little telegram, telling the time that the train would get in, and what time you would be at their house, and off that went. And then when you got to the new town, we always took taxis, unless you’d been to the town before and you knew it was within walking distance.

Patricia Linton: How did you do your washing? You know, your clothes?

Noel Bronley: All our washing in the theatre, it was all done in the theatre. We hung it up on lines in the dressing room. No, the other thing was, that was our tights and things, our pants, but every theatre had a laundry. The main thing about that was that you were very, very lucky if you ever found cotton wool in the shops. It’s like Kirby grips, elastic. If somebody found something in the shops, word would go round like that, and the locusts would just descend, you know. You couldn’t buy cotton wool; so what we used to do was, torn up old rags, sheets, which your mother would give you, and we had this terrible, huge, great tins of greasy, “Cremona” “Cremene”? that’s right, which you plaster on your face, and then take off with these ghastly rags. The laundry took those rags, and they came back, they were stained and coloured, but they were always clean. How they ever did it, I don’t know. So that was one of the things that we did, and that was, as I say, relatively cheap.

Patricia Linton: Did you have a home in London?

Noel Bronley: I had. Not most people – people who had been brought up in London, yes. Grace lived in Dartford. Patti Board lived, um, in Essex somewhere, I think. Joan Tucker lived in London but, of course, there were others like Judy Forster who lived in Newcastle. Herida [May] and Judy Forster had been at the same dancing school.

That was the other interesting thing, when I went into the Wells School, Herida, she’s the same age as me, so she was in the school. And Auntie May [Attewell], this dwarf lady who was her auntie, used to take her and collect her each day, and I think Herida was a huge favourite of [Nicholas] Sergeyev’s, because she was tremendously strong. If he gave her 32 développés to do, she would do it, and she had this will of iron, and she was one of our Lilac Fairies. She and Sandra Vane, and it’s a hard, hard solo. Those développés, you know, it’s really hard, and Herida carried it off like that. Which, in 1942, you didn’t see that sort of strength very often.

This is the other interesting thing about Mona [Inglesby], the way she arrived at stage names. Ivy, the Latin for Ivy is hedera. You know, the Ivy. She turned it round, Herida. She took auntie May’s name, Herida May, and with me, and Drew Hardy had suggested it with me, because he felt my profile was like Bronislava Nijinska’s and it is, this sort of receding chin. So he said something to do with that, so it was Noel Bronley.

Patricia Linton: And what was your name?

Noel Bronley: Noel Brown. Mrs Inglesby, when she took rehearsals, she only ever used surnames, and it used to be, ‘Brown, Brown, what are you doing?’ Her mother, Mrs Inglesby, the dragon, she was sort of in overall charge of the wardrobe. She had Auntie May, Herida’s auntie, who was really the wardrobe mistress

Patricia Linton: Did you mention that Mrs Inglesby took rehearsals?

Noel Bronley: Yes, she did. Yes.

Patricia Linton: So she was in charge of wardrobe, overall in charge of costumes and wardrobe. Had she been a dancer?

Noel Bronley: No, no, she hadn’t.

Patricia Linton: Did she have a good eye?

Noel Bronley: Difficult to say. There were certain things that she rehearsed, and we were called for rehearsals with Mrs Inglesby. I mean, it was an official thing. A lot of the time, she was just rehearsing us for togetherness. So we would do [Les] Sylphides to counts 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 without music, you know. Which I expect was very, very good, and she could see if somebody was out, and she would… she would bawl at them.

Patricia Linton: So she knew the ballet really well?

Noel Bronley: No, she didn’t, really. There was one rehearsal. We had this one dancer who was really awful. She, was in the company. I don’t know whether it was a financial gain for Mona that she was in the company or what it was, but she was absolutely dreadful, and I forget, I think it was Swan Lake, and Mrs Inglesby was rehearsing us. And you know, the temps levé pas de chat. Yes, that’s right, yes, the basic step. Mrs Inglesby thought we weren’t doing it properly, and this included Herida May and Sandra Vane, who were both soloists. And so she said, ‘The only person who is doing it right is so and so,’ she said, ‘Now, you go and demonstrate it, dear,’ and this ghastly girl was demonstrating this stuff. I mean, I expect she was as embarrassed as the rest of us, but Mrs Inglesby didn’t really know what she was doing. And she could be so rude, and so vitriolic. Beautifully dressed, beautiful clothes, lovely hats, and lovely shoes, and she used to stalk round the floor, the stage, saying, ‘You’re not doing it properly, you’re not doing it properly,’ but she didn’t know what we weren’t doing properly, you know. Extraordinary.

Patricia Linton: Why did people stand for it? Did people leave because of her?

Noel Bronley: We didn’t, we didn’t. There was a rebellion, I think, probably at the Adelphi, and we said that we weren’t going to put up with it anymore, and Mr Inglesby came down and said, ‘If you don’t like it, you know where you can go.’ Mr Inglesby came on stage and said that.

Patricia Linton: That was?

Noel Bronley: Mona’s father, who had given her the original £5,000 to set up the company.

Patricia Linton: And did anybody ever leave because of her? Did Mr and Mrs Inglesby want the company for their daughter, or were they also interested in it for themselves?

Noel Bronley: No, I think, um, it was for a vehicle for Mona. We very seldom saw Mr Inglesby. There wasn’t really a place for Mona. I thought she was, a brilliant dancer. I remember at the funeral, Mona’s funeral, Rhona saying to me ‘You are so lucky to have seen Mona in her prime,’ and I said, ‘What do you mean? Had she gone off?’ and Rhona said, ‘Oh yes, by the time the company closed, she’d gone off a lot.’ And of course, one of the things was not just age, but the fact that, as far as we know, Mona never did class. She warmed up, she did a class, but nobody ever gave Mona a class. I think,

Patricia Linton: She was never corrected.

Noel Bronley: She was never corrected.

Patricia Linton: Or helped, or coached, or rehearsed even.

Noel Bronley: That’s right, exactly. I think maestro [Sergeyev] probably would have corrected her, but I suspect he was always too busy with the choreography to notice anything bad that she was doing. And that, that peak, probably when I first went, I think she was probably at her peak when I first went into the company. She didn’t have very many bad mannerisms, but she did develop some very bad ones. She, she turned her hip badly, horrendously in, in arabesque, and she had this terrible thing that she did with her pointe shoe. In order to make her foot look more turned out, she pulled the heel of her pointe shoe almost round to…,

Patricia Linton: To the inside.

Noel Bronley: To the inside, almost to the ankle bone with her, shoe ribbons. And so that meant that when she went en pointe, she was practically on her big toe joint, and that got worse and worse, and, of course, there was nobody to tell her not to do that.

Patricia Linton: Inevitable that the company would decline? If not for financial reasons and popularity reasons.

Noel Bronley: I know she was heartbroken. Everybody kept saying to me, ‘Why did the company close? Why did the company close?’ Well, if it hadn’t been forced to close, because the Arts Council withdrew their grant, which is why it closed, she would never have given up.

Patricia Linton: So what was the reason?

Noel Bronley: Well, Audrey Harman said, and I’m glad it was she who said it, that it was because [Ninette] de Valois vetoed it. [De] Valois was on the Arts Council, and she vetoed it. Now, Audrey was, um, a member of the Royal Ballet. She liked de Valois, and she had no reason at all to say that if she didn’t believe it was absolutely true. In the meantime, it’s quite a comforting thing to be able to tell the ex-members of the International Ballet who are still saying, you know, in their eighties, ‘Why did we have to stop’?

Patricia Linton: Even if in the worst light it could be seen as a vehicle for her.

Noel Bronley: For her, exactly, yes.

Patricia Linton: Um, would that be unfair to say it like that?

Noel Bronley: No, I don’t think that is unfair, because, nobody else was going to make the vehicle for her. So for Mona to borrow £5,000 from dad, and create a vehicle for herself, I don’t blame her at all. Plus not only was she doing something to give pleasure to a huge number of people, I think there was an element, probably, of sucks boo to de Valois and [Marie] Rambert.

Patricia Linton: Mm.

Noel Bronley: Which, to be able to do that at 23 was quite something, wasn’t it?

The transcript of this podcast may have been lightly edited for ease of reading.