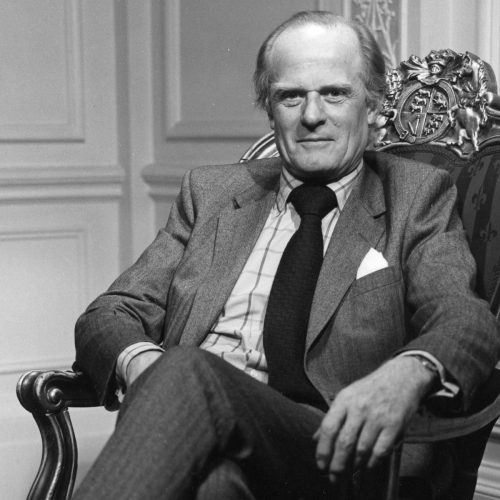

John Tooley

If ever a job needed diplomacy it must be as General Director of the Royal Opera House, a post John Tooley held from 1970 until 1988. He was also Assistant to the General Administrator from 1955 to 1960, followed by 10 years as Assistant General Administrator. Here he gives Bruce Sansom a few examples from his early years of how true the need for diplomacy is. He speaks about the diplomatic crisis surrounding the visit of the Bolshoi Ballet in 1956, about arranging American tours for The Royal Ballet, about his admiration for “Madam” (aka Ninette de Valois), and about the circumstances of Frederick Ashton’s retirement in 1970.

The interview is introduced by Anthony Russell-Roberts, the former Administrative Director of The Royal Ballet who died in January 2024, in conversation with Natalie Steed.

First published: April 8, 2025

Biography

Born in Rochester in 1924, John Tooley was educated at Repton and Magdalene College, Cambridge. For much of this time he had ambitions of becoming a professional singer. Although he judged he was not talented enough to make a career in singing, his interest in music remained, and he planned on becoming a musical administrator. To prepare himself for such a role, he spent a few years working in management at the Ford Motor Company.

In 1952, he was appointed Secretary to the Guildhall School of Music and Drama. His long association with the Royal Opera House at Covent Garden began in 1955, when he became Assistant to the General Administrator. Five years later, in 1960, he was given the position of Assistant General Administrator, working alongside the General Administrator, Sir David Webster, until 1970, when Webster’s health became uncertain. Tooley was then promoted to being General Administrator. He held that post for 10 years until 1980, when it was re-named General Director. It was as General Director that Tooley retired from the Royal Opera House in 1988. He was knighted in 1979.

Transcript

In conversation with Bruce Sansom

John Tooley: My name is John Tooley, I was born in Rochester, Kent, on 1st of June 1924. We had, what I’d describe as a very conventional middle-class upbringing, life was very good.

Bruce Sansom: What did you know of the Opera House, then, whilst you were at Repton?

John Tooley: I knew quite a lot, actually, as I had read about the history of the inter-war years, but I’d not been here because we were living away from London – I’d been living in Bath. Whenever the ballet came to the Theatre Royal, which they did periodically, with Hilda Gaunt and Constant Lambert on two pianos and Margot [Fonteyn] and Bobby Helpmann, and so on, we used to go a lot to those performances. I remember Constant’s very refined, highly musical playing against Hilda’s rather, sort of, rougher course of playing, which was reflected in conversations I had with Hilda after I came here and got to know Hilda. She said, ‘Oh don’t worry too much about the wrong notes, John, just keep the rhythm going, that’s all you’ve got to do’ [laughs]. It was actually during the war, when Sadler’s Wells Ballet was on tour, that I really came to appreciate what all this was about.

Anyway, I then decided that I really would go into musical management and I looked around a bit. I looked at music publishers, I looked at agents, but decided I wasn’t going to learn much. I thought, ‘Well, the only thing to do is to go out into commerce and get some experience at management and… I found the Ford Motor Company in Dagenham, where for the first time [they] were employing university graduates. I had been there, I suppose, about 3 and a half years when I read an ad in The Times for the post of secretary for the Guildhall School for Music,. Anyway, there were a lot – I gather something like 400 applicants for the job – but by a miracle I got it, and I had a wonderful time at Guildhall. It was a great teaching staff. Edric Cundell was the principal, and I had been there for about 2 and a half years, when I got a call from David Webster, of the Opera House, saying that he wanted to talk to me.

We’d met previously, and Edric Cundell was also on the board actually of the Opera House, and Webster had said, ‘I’m looking for a replacement for Steuart Wilson’ who was then deputy administrator, and Webster decided that he wanted somebody younger, who would go in as an assistant and Cundell had said, I gather at a board meeting, ‘Look there is John Tooley. I don’t want to lose him, but [he is] somebody maybe you ought to see’. Webster apparently said, ‘Yes, look I do remember him, I think he and I should meet’, and that’s how I came to Covent Garden.

Bruce Sansom: So then you arrived September 1955?

John Tooley: I arrived in September and Webster said, ‘Terribly sorry, I haven’t got anywhere for you to sit’. And then in November of that year he and de Valois had been to Moscow, and he said, We have an agreement in principle, an outline for a visit of the Bolshoi Ballet to Covent Garden in the Autumn of 1956; over to you, you fix it’.

And we got sort of everything into order as far as we could tell, but then there occurred an incident, which was to cause the postponement of the visit of the Bolshoi and that was Nina and the hats – the Russian athlete [Nina Ponomareva] who had been into C&A Modes in Oxford Street, and was accused by the store manager of having stolen a hat. This caused an immediate diplomatic incident, and persuaded the Bolshoi itself, led by [Galina] Ulanova, to write a petition, which was then sent on to us in London to the effect that there was no way in which the company would come to London for fear of victimisation. So it was a major drama, but after a lot of discussion – both at diplomatic levels and also between Webster and [Mikhail] Chulaki, director of the Bolshoi – it was agreed that it would go ahead.

The day for the company to arrive came and I went out to the airport, to London Heathrow, to meet them. It was not a very good day, weather-wise, and we had been standing there for some time, the Air Attaché from the Soviet Embassy was there plus the Cultural Attaché. Suddenly there was the most God-almighty explosion, flames bursting into the air and smoke, and of course, we thought, ‘My God that’s the Bolshoi’. But what it turned out to be was a Vulcan bomber, which had actually crashed just on the sort of perimeter of Heathrow.

I can’t remember, I think we were opening on Tuesday, on Sunday we had the first orchestral rehearsal alone. The two conductors were Yuri Faier, who was an amazing musician and a really wonderful conductor; he was nearly blind and he could only see dim shapes on the stage. The other assistant conductor was Gennadi Rozhdestvensky, a very young musician. They came to rehearse and they got to the sword dance in Romeo [and Juliet] and they played the sword dance in tempo. Yuriy Fayer put the baton down and turned to us, and he said, ‘I don’t believe it, they’ve been rehearsing beforehand’. And I said, ‘No, look, British musicians are brilliant sight readers’, and I said, ‘That was sight read’ and Fayer said, ‘I don’t believe you’.

He said, ‘It is absolutely breath-taking.’

We had a lot of problems with the scenery. Scenery was never fire proofed and the fire authorities were never happy, and as I explained to them, I said, ‘Well, look, if you go to the Bolshoi, to the Kirov, all they do is to employ more firemen in the hope that if there is a blaze, they will put it out.’

Anyway the day came for the company to go back. So I went up very early into Heathrow, and there were 3 very ancient Russian planes on the tarmac, and in those days you would walk across the tarmac, there was no security. And, actually, I walked across the tarmac with the Chief Executive of British Airways, and he said, ‘You look at these planes. They’re so unstable, they have to put a fin down the top of the fuselage to keep them upright’.

Now the weather was bad, and I said to the Air Attaché, ‘Everybody here is telling me this makes no sense at all, to take off in this weather.’ So I said, ‘What are you going to do?’, and he said, ‘We’ve got to get out’. And he said, ‘What we’ve now decided to do, because we’ve only got these small planes, is in fact to take the company out in two batches, and we’re going to fly to East Berlin and leave the company, come back and pick the rest up, and either fly them to East Berlin or, if the weather’s better, we’ll fly them on to Russia, and the company left in toto, and by some miracle they got to East Berlin safely. The next morning the Hungarian invasion happened.

It was an extraordinary season and that was the steepest learning curve I have ever been through, I think.

Bruce Sansom: And can you remember the performances, I mean it was a turning point for a lot of members, early members of the company to see people like Ulanova….

John Tooley: Yeah, there was this extraordinary Romeo and Juliet and of course what you saw in that, and particularly in the big ballroom scenes, was in fact the weight and gravitas of a lot of the people on the stage, simply because of their decision to go on employing dancers after normal retirement age purely as dancers. Either as character dancers or just, literally, I mean walk-on. And it created an extraordinary impression, but above all of course it was [Galina] Ulanova, and nobody who ever saw her do that run off the stage will ever forget it.

But the only other direction I’d ever received from Webster, apart from the Bolshoi, was, ‘John, take the Royal Ballet to New York.

Bruce Sansom: Right. And so you met Sol Hurok and…?

John Tooley: Yup, and then with Sol, of course, with Sol it became a very close relationship and friendship; I did all the American tours.

Well with Sol Hurok, you know throughout the 1960s they never had a contract. He and I would meet at the Savoy Grill for lunch and we would talk about the tour and, about half way through lunch, he would say, ‘How much?’ So you’ll say, ‘We need X thousand dollars per week, Sol’. ‘Too much.’ So you would agree another figure, which I knew would cover our costs but would reduce the profit margin a bit. And if anybody collected the tablecloths from the Savoy, all of these things were written out by Sol in black felt pen on these tablecloths. That was the contract and I trusted him, and it worked absolutely.

Bruce Sansom: I’m intrigued, in this position, how much contact you had with people like Frederick Ashton and Madam [Ninette de Valois]?

John Tooley: Madam I had a lot because I’m going to come on to something else. The de Valois/ Webster relationship was not at the best, and she increasingly started to use me as the go-between. When she retired, I said, ‘Madam, one thing you’ve got to be sure about is that I will miss my telephone wire being wound up to white heat by some fury of voice at the other end complaining about the iniquities of the opera or whatever’.

Well, I loved her. I mean, she was an incredibly handsome woman. I admired hugely her vision and I quickly understood her pragmatism.

She entertained me a lot. I loved her mimicking of Alicia Markova, for example, or Lilian Baylis, and she always used to say to me, she’d say, ‘Well, I’ve learnt so much from Lilian Baylis.’ She says, ‘It’s left a mark with me now and that’s why I can never go in the taxi’. She says, ‘I can’t bear to see that meter clocking up, it makes me sick’

Bruce Sansom: And what was the process when Madam decided she was going to retire?

John Tooley: Well, she simply said, ‘Ashton is here’.

It had all been taken as read, like a lot of things in this place, for a long time. [laughs] And it was the same when we were getting up to the crisis with Ashton at the end of 1960s and going in 1970. You see, de Valois, towards that, said, ‘You know Fred’s got to be sensible, he’s got to stand down; he’s been here long enough, he must go’. But she had no authority in that direction and since we’re on that subject, it’s an interesting one, and one that alarmed me a great deal. I would have loved to have worked with Fred as Director for some period, and it hadn’t occurred to me in the mid sort of sixties, that Ashton was likely to go when Webster went. Webster had said eventually, ‘I’m going to go in 1970’, and then he, one night at the Crush Bar – we were having a drink – and he said, ‘Of course you know, Fred’s going with me.’ So I said, ‘Well why, David? Why is he going?’ ‘Oh well, Fred’s told me that he will go when I go; he doesn’t want to stay after I’ve gone.’

And that, what actually was a myth, and I always believed it was a myth, persisted right through to the end. And, in 1969, Webster had arranged to see Fred, and Webster was getting increasingly anxious about this encounter with Fred, and said, ‘John, I would like you to come and be with me.’ So actually I couldn’t be with them at the beginning of that session – I was in some other meeting – and I said, ‘Well, look, I can’t break off; I will come and join you as soon as I can.’ And I went into Webster’s room and there was Fred looking incredibly shaken and very upset, and as soon as I walked in and started to sit down, Fred turned to me, and he said, ‘John I’ve been sacked.’ And I said, ‘Well you can’t have been sacked,’ and Fred said, ‘I have been.’

Bruce Sansom: How did the meeting end?

John Tooley: Well the meeting ended in a lot of really bad feeling, and it was clear to me that Webster piled a huge problem on his head, Webster’s head, and that this, in fact, was going to have serious repercussions on the Royal, causing what I considered was a totally unnecessary crisis on the one hand, but much more importantly than that, was depriving the Royal Ballet of its largest, most talented creative force. Fred was still very creative, and I couldn’t for the life of me see the point of it.

Although David was not at all well – in the last three years, frankly, I had virtually run the place. I mean Webster had really been missing out on an awful lot of things. And he began to sort of have a sort of grudge about going. I mean the going was really very embarrassing, he was so tearful and collapsed into tears at the farewell performance, and I think somehow David didn’t want to be seen as the sole person leaving, and that, somehow, he was going to get some strength for himself if Ashton went with him. It’s the only conclusion I can come to, I mean… It’s tragic, because Fred was good for a lot more creative work, and certainly the company was deprived of that for some time.

The transcript of this podcast may have been lightly edited for ease of reading.