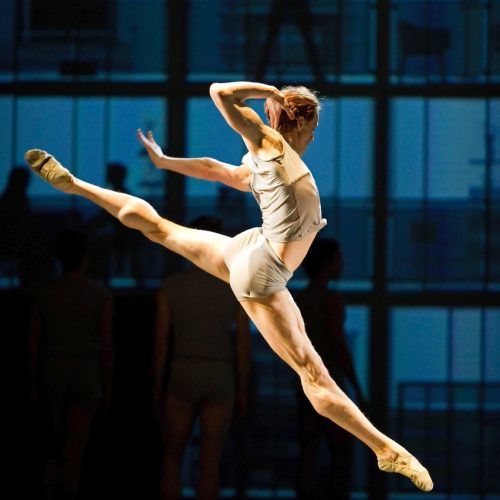

Edward Watson

Over a long career, Edward Watson became one of The Royal Ballet’s greatest male principals, in the footsteps of Anthony Dowell and David Wall. He is particularly noted for his work in the ballets of Frederick Ashton and Kenneth MacMillan, and for creating many roles with contemporary choreographers. Here, in a conversation with Jane Burn recorded for Voices of British Ballet in 2007, he speaks disarmingly about his early days in The Royal Ballet before sharing some insights about portraying Crown Prince Rudolf in MacMillan’s Mayerling, a role for which he is particularly associated. The interview is introduced by Kenneth Olumuyiwa Tharp.

First published: January 13, 2026

Biography

Edward Watson was born in South London in 1976, and trained at The Royal Ballet School, first at the Lower School at White Lodge, and then at the Upper School in Barons Court. He graduated into The Royal Ballet in 1994 and was promoted to the rank of principal dancer in 2005. Watson’s pure classical technique, combined with a fine dramatic flair and sensitivity served him well in the works of Frederick Ashton, Kenneth MacMillan and Ninette de Valois herself, choreographers at the heart of the British tradition. He has himself been a major force in the continuation of that tradition.

Apart from lighting up ballets from the existing repertoire, Watson is noted for his commitment to new work and for his enthusiasm for working with contemporary choreographers. These include Wayne McGregor, Christopher Wheeldon, Kim Brandstrup, Cathy Marston, Arthur Pita, Javier de Frutos and Alexei Ratmansky, among many others.

Edward Watson’s awards and distinctions include the 2012 Olivier Award for Outstanding Achievement in Dance, the 2015 Benois de la Danse Award and the Critics’ Circle Awards for Best Male Dancer in 2001 and 2008. He was appointed an MBE for his services to Dance in 2015. As well as performing at the highest level, he now works internationally as a répétiteur.

Transcript

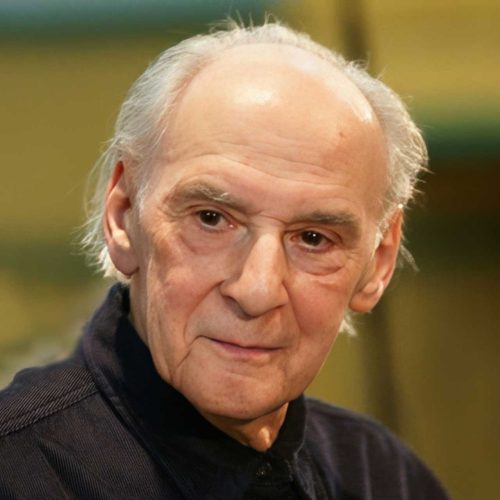

Jane Burn

Edward Watson: They [the BBC] were making a film at the time about the [Royal] Opera House called The House and I was in a character class in the Arnold Haskell Studio [at The Royal Ballet School], and Rashna Homji, who was the… I guess the assistant director of the school… came to the door and said, “Dame Merle [Park] would like to see you, Christina… Edward,” and I was, like, “Oh God! What have we done?” And she [Dame Merle] said, “Would you like the good news or the bad news? The good news is… Anthony Dowell would like to offer you both jobs with The Royal Ballet company, but the bad news is that I want you to stay at the school until Christmas,” and we were like, “OK, that’s not such bad news, I guess.” I just remember being, both of us, Christina and I, being completely, sort of in shock… and, you know, having just been in the middle of your normal day, being called out – the film crew there and being told that you’ve got what you’ve always wanted, you can’t… it’s kind of hard to take in.

Jane Burn: So, you do start life in The Royal Ballet company. What were your first impressions of that?

Edward Watson: Well, I was terrified! Terrified to walk into the changing room to start with, because at that time… all the men shared one big dressing room, and you walk in the door and you can see everyone looking at you going, “Uh, it’s the new boy!” And I remember walking, like, two steps in, and I walked out and got changed in the School changing room. And also just walking to the class as well… not knowing where you can stand at the barre, who stands where and, you know, having to wait till everybody else took their place, but you, you kind of have to get used to the sort of hierarchy of that, you know, the principals, and the soloists, and the corps de ballet, and you’re like at the bottom, the scum! You know, you have to wait and hang on to the piano for a while… but the more you get into rehearsals, and the more you have to ask people questions about, you know, “Oh, what was that step?” that, you know, you get more comfortable with people and they get comfortable with you, and… yeah, sort of become part of the company very quickly actually.

Jane Burn: So, you talk about being at the bottom of, as it were, that hierarchy. Can you remember what some of the opportunities were, for you?

Edward Watson: The first thing that I did, that I was sort of vaguely featured [in] was [Frederick Ashton’s] Rhapsody… the six boys in Rhapsody. It was in my first year in the company, and I was thrown on – Yohei Sasaki was sick – at a couple of hours before. And I’d been at the rehearsals learning it and things, but… I didn’t really know what I was doing. I’m a bit terrible like that, unless I know I really am going to do this thing, I never really learn anything properly. It’s terrible! I still do it now!

So, I was sort of thrown on and I made a massive mistake, actually. Everyone was doing… there’s a step in it where people, all, you know, where the six boys are all doing the same step; and I did the wrong step. So, I was sort of in the middle [laughs] of these five other boys, and they were all doing changements, and I’m doing brisé volés on my own in the middle. I can’t even do brisé volés very well, but I had to do about 20 to catch up. It was shocking, and I… yeah, that kind of affected me for [laughs] a very long time. That sort of… being on stage and not really knowing what I was doing, that was a first for me. And then I never went back into it again! I think I did two performances until he [Sasaki] was better and then… I don’t think I made a very good impression. It wasn’t like they gave me an opportunity, and I really seized it, and made something of myself… that didn’t happen.

I think it must have been the year after. Luke Heydon was injured, and they [The Royal Ballet] were doing [Kenneth MacMillan’s] The Judas Tree, which has a lot of boys in [it] and so every – all the boys in the company – you were, kind of learning a part in it, and I learnt, just happened to learn a part that Luke Heydon did. He had a tiny little solo in it, a sort of strange solo right near the beginning… very difficult music, and he was injured. So, I was on… the first night, and I had a few rehearsals, and I was terrified. I had to come on and sort of trash around and be wild and sort of aggressive, and that sort of wasn’t me at that time, and I think from that being my first, sort of, solo… I guess, still must have been my only second year in the company. Now, when I look at it, that very much shaped the work I do now. It wasn’t classical at all. It was sort of expressive and part of a story and, without realising, I think that’s what probably people saw me do first and thought, “Oh that’s what he’s like then!” [Laughs]

Jane Burn: So, during Anthony Dowell’s directorship, you did rise up through the ranks?

Edward Watson: Yeah, I think Anthony made me a soloist just before he retired. Actually, the season before, but I remember him saying to me, “I’m going to make you a soloist because I want you to do [Antony Tudor’s] Shadowplay, and [MacMillan’s] Gloria, and [Ashton’s] La Valse and try out all, coming up that season.” And it was the first time I’d had one of those throw away sheets, where you see your name down for big roles and you go, “Oh, OK”. That was amazing to be made a soloist for The Royal Ballet. I can remember being kind of… [Quietly] “I think I’ve made it!” [Laughs]

Jane Burn: So, you went through quite a period of change when…

Edward Watson: Anthony left.

Jane Burn: Anthony left.

Edward Watson: Yeah. That was kind of, that was a very… funny year. I mean, it was only a year, but it seemed like a lifetime, I mean for a lot of us. Ross Stretton was made director, and nobody knew anything about him at all. You know, when it was announced, we were all sat in the studio and said, “Ross Stretton is going to be your director,” and we were like, “Who? Who is that? Who is this person, coming in here and is going to tell us what to do?” So, there was already this sort of… tension, everybody had. I mean, there was bound to be, with a new director, but… it was somebody that no one had heard of. I mean, obviously he had been around, and had been a director of [The] Australian Ballet and things, so um… but there was already a lot of, sort of bad feeling, from people saying, you know, “This man shouldn’t be here. He’s not British, he’s not come through the school, he’s never been in The Royal Ballet, he doesn’t know about the repertoire.”

So, we all kind of started that year with that feeling. But at the same time, everybody wanted to impress him, because he had our careers in his hand. It [was] sort of a time, particularly for me and other people, we were sort of young soloists just starting. You kind of had it all in front of you, you thought… and he just came in and did exactly what he wanted to do, really. He wanted to discover his own people, he wanted to bring in his repertoire, you know. It wasn’t like he wanted to pick up where Anthony left off, which you know, now, I can look back, I can see, well of course he was going to do that, but at the time you are sort of outraged and you know, “Who does he think he is? I’ve done these roles,” and you know it really was like that.

I’d been a soloist and done a few principal roles, but now I was sort of back in the back row of Onegin 12 couples, you know, doing a polonaise, and a step and a hop with people who had just joined the company. It was a very strange year in terms of company morale, and the way people, you know, behaved with each other. There was lots of in-fighting. There was a real camp of people who thought he was great and, you know, quite a big camp who thought he was making a big mistake.

Jane Burn: And where did you see yourself in all that? You say that there were some roles that you felt made you step back into the corps de ballet.

Edward Watson: Yeah.

Jane Burn: But were there opportunities, too, in some of that?

Edward Watson: Yeah, absolutely. There were things like Remanso, a Nacho Duato ballet, which was supposed to be [for] Carlos Acosta, but Carlos had upped and left, but it was on with the programme with, what’s is it called? The Vertiginous Thrill of Exactitude, a William Forsythe ballet, which I had been cast in, and they were in the same part of the programme. And nobody had kind of realised that I was doing Remanso and the The Vertiginous Thrill of Exactitude, which is a killer. I mean, it’s non-stop, full on, everything to the max, you know? Real puffy dancing, and they were back-to-back, with a 90-second scene change and, I was like, “Do you realise that I’m having to do both of these?” And, you know, his [Stretton’s] face turned white briefly and he said, “Well, they don’t want anyone else to do it. They want you to be on first night for both,” and I was like, “And what do you want?” He went, “I think you can handle it.”

That’s all he used to say to me, [puts on a funny voice] “I think you can handle it.”

So, there I was, you know, I think, proving myself that I was capable of more than doing the back row of Onegin 12 couples. And I think that turned round, a little bit of steeliness within me to go, “Yeah, OK then. I will handle it, and I’ll do this,” and that sort of became what happened that season. I, sort of, did more and more, and he ended up promoting me at the end of it, to a first soloist. So, from my memory of him, [it] was that he didn’t like me very much, but then I can think, “Well he promoted me at the end of that season, so there must have been, I must have done something right.” [Laughs]

Jane Burn: And after Ross Stretton, Monica Mason…

Edward Watson: Monica was the assistant director the whole time during, that I’ve been here, and she took over the company and immediately… this massive sense of calm kind of happened. Things sort of settled down a bit.

Jane Burn: I’d love to ask you, obviously, about Crown Prince Rudolf [in MacMillan’s Mayerling].

Edward Watson: Mmm. [In agreement]

Jane Burn: Which recently you performed, and you’ve received great critical acclaim, not least for this creation of a wonderful character.

Edward Watson: Mayerling is something that I… it’s a ballet I always loved and was completely amazed that someone could tell that story through dance, and not just get away with it, but make people, you know, be kind of numb at the end of that ballet. You know, you’d watched it and think, “What an experience!” But the role is, kind of, renowned for being the toughest male role, probably, in ballet.

Jane Burn: Just the physical side? Did you train in a particular way for this role?

Edward Watson: Yeah, I upped my sessions at the gym, basically! [Laughs] I have a personal trainer who makes me lift weights, three times a week, and I up… no, twice a week, and I upped it to three times, in preparation for Mayerling because I knew that it’s tough. You know, you, if you’re not walking somewhere, you’re lifting someone. I’m not a big built kind of person, and I think a lot of eyebrows were raised when they saw my name down that I was going to do, sort of, this biggest weightlifting partnering role in the [laughing] repertoire. I think a lot of people were probably appalled. And I was a little bit, I was like, “Oh, OK”.

I wanted to do it justice. I didn’t want to, just, people to say, “Oh yeah, you know, Ed Watson, yeah, he got through it.” I wanted to be really good in it. It’s such a strange ballet that… there’s so much in it. You can stand there at the beginning, you know, you walk on before the procession and you can see what you’ve got ahead of you, and you just think, “Oh, I’d just rather walk the other way and go home,” because you know how you’re going to feel at the end. But you start… everything just happens to you, you’re caught up, actually, like the character is in this life, and everything. It’s like you live a whole lifetime in that ballet. It’s such a strange experience, you feel like you’ve lived a lifetime, and it’s almost like coming out of something at the end of it. You… It’s sort of a strange, sort of daze. You don’t really know what you have done, and what you’ve been through and you’re stood on stage… on your own at the end, and it’s, yeah, it’s wonderful and, yeah, you go through everything you know, and things that you don’t know and, I guess, a lot of MacMillan ballets are like that. I find that you – I – discover more things with every performance of his ballets, somehow. About me, about life, about what I’m capable of, and things. It’s kind of a funny thing to put into words, really.

Jane Burn: A very different experience from dancing in one of the big classics.

Edward Watson: I’ve never done a big classic. [Laughs] I’ve done Giselle!

Jane Burn: Giselle?

Edward Watson: Giselle, yeah. Giselle is different. I’ve never… they’ve never put me in Swan Lake, or [The] Sleeping Beauty, or Don Quixote, or anything like that, because I… While I’m, you know, really classically trained, I think the sort of extremity of my technique wouldn’t really lend itself so much to being immaculate, in that kind of way where there are so many rules in classical ballet that, you can tell very easily if someone’s not perfect, and I’m not perfect. So, Giselle is different because it’s such an amazing story. You don’t feel like you’re up there doing your solo and then your pas de deux, and people wait at the end of it to clap. It’s in the same way as Mayerling or Romeo [and Juliet] – you get involved from that start, you know you’re not just a prince who comes on and kisses someone, and they wake up. He’s [Albrecht in Giselle] not a nice guy, really. To start with, he’s spoilt and used to getting what he wants, and he’s seen this village girl, and thought, “Oh yeah, I’ll have a bit of that.” And then he goes through this journey at the end of [which], you know, he realises that you don’t treat people like that, [laughs] and how that kind of behaviour affects people. That’s the way I, kind of, approach everything, from the story point of view, and if it’s good choreography, then you don’t need to do a hell of a lot else, apart from the steps… I don’t go into Giselle, Mayerling or Romeo thinking, “Oh, this is going to be, it’s alright, I can act my way out of this.” It’s not an acting exercise. It’s a ballet, and the steps shape the character, and shape the situations and the story; I always approach it, steps first, you know.

The transcript of this podcast may have been lightly edited for ease of reading.