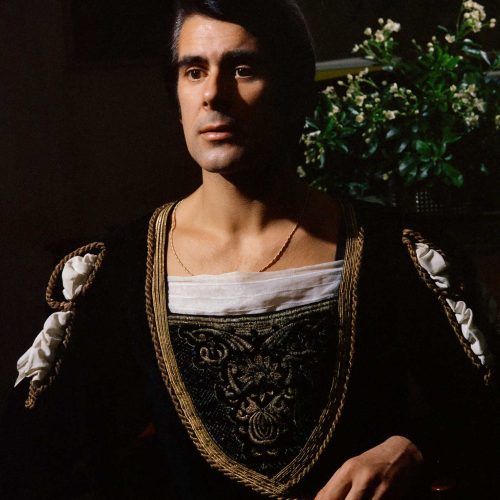

Donald MacLeary

In this podcast featuring Donald MacLeary, the ballerina Darcey Bussell makes a fascinating and full introduction to her friend and mentor. She stresses the importance of a coach who is both knowledgeable and intuitive, for a dancer flourish. The backbone of British ballet is storytelling and both Darcey and Donald underline how important it is to keep this tradition alive. Donald Macleary is in conversation with the dance critic Alastair Macaulay.

First published: September 9, 2025

Biography

Donald MacLeary was a dancer noted for his finesse and natural romanticism, and for his legendary partnering skills. He had an association with The Royal Ballet for 48 years. Born in Glasgow in 1937, he studied ballet with Sheila Ross from 1950. He then went to the Sadler’s Wells Ballet School and joined Sadler’s Wells Theatre Ballet in 1954. In 1959, when Svetlana Beriosova asked for him as her regular partner, he moved to The Royal Ballet at Covent Garden, becoming its youngest principal dancer at the time.

MacLeary created roles for John Cranko, including in Brandenburg 4 and 6 in 1964, and for Kenneth MacMillan, including in The Burrow (1958), Symphony (1963) and Elite Syncopations (1974). After his retirement from dancing in 1975 he was appointed ballet master for The Royal Ballet from 1976 until 1979. He later appeared as a guest artist for a number of companies, including Scottish Ballet, and was a répétiteur at The Royal Ballet from 1981 (for principal dancers from 1984) until his retirement in 2002. Donald MacLeary was appointed an OBE for services to dance in 2004.

Transcript

in conversation with Alastair Macaulay

Donald MacLeary: We’ve had good teachers, but I’ve always thought by myself, I’ve been more influenced by Albert Finney than I have by… I don’t know, somebody in the company, but I was always very interested in thinking the role, not just doing the steps, telling the story, and that’s what I love about the classics. There is a story, but they’re not always told very well. And that really worries me. It’s all about how high you can get your leg up and, you know, ‘aren’t I clever doing thousands of pirouettes’, and they’re not telling the story.

Alastair Macaulay: The actual science of partnering, because you are one of the legendary partners. Did that come to you during those early years in The Royal Ballet School?

Donald MacLeary: Yes, I mean, I still wasn’t very good when I joined the company, but very early on I was given Les Sylphides. I was 17 when I did Les Sylphides.

Alastair Maculay: And that’s a hard partner?

Donald MacLeary: And there’s a lot of lifting, and not a lot of pirouetting, but a lot of lifting, and I had quite a large lady to do it with, so that made me strong. And every time you’re given something, you learn something else. So, I then did Les Patineurs pas de deux with somebody called Margaret Hill, who was amazing and… this is a story against myself. I concentrated like mad on the first time we did it, and it went very well, and the second time I did it, I was enjoying myself too much and I nearly dropped her. And that taught me a lesson: concentrate. That[’s what] I always say to everybody: concentrate, concentrate, concentrate.

Alastair Maculay: But you acquired this kind of science (well, if that’s the word) or instinct where ballerinas would say, ‘he could tell if I was going to be in trouble before I knew I was in trouble’. How does a man acquire that?

Donald MacLeary: Well, I mean, the technique, the dancer’s technique is the same male and female, apart from the fact that they’re on pointe and we jump more. But you, actually, you know, if you’re doing a double en dehors turn, you have to have your weight in the right place. You have to think, you really have to think about, you know. And I mean, I used to when I stopped dancing, I then coached. And if somebody was having a problem, I wouldn’t say, ‘Do it again, do it again, do it again’, like some people do, because you haven’t come up with the answer and you might have an injury on your hand because they’re getting exhausted. So, I used to go away, maybe driving, thinking about it or just thinking about it and come back the next day and say, ‘Try and do it this way’ because there are more ways than one and everybody’s body is different. So, you can’t treat people like machines. You have to find out their weaknesses and strengthen their weaknesses.

Alastair Maculay: When did you first start to do these princely roles that were an important part of your work, and when did you first start to work with choreographers?

Donald MacLeary: Well, really, almost at the same time. I was very lucky that Kenneth MacMillan was a dancer in the company when I joined the company, dying to be a choreographer, and he decided to give up. So, I got all his roles. I got Blood Wedding, the Moon in Blood Wedding, the Existentialist in Café des Sports, Sylphides. But he [MacMillan] was doing [choreographing] Danses concertantes for us at that time, too. So, I was being choreographed on at a very early age and I did three roles in Concertantes actually. I did, originally, that’s one of the side boys that were two side boys. And then I did the pas de trois. Then I finish up doing the lead role, the pas de deux which I did for ages, and put it on in [American] Ballet Theatre and put it on at the Paris Opéra [Ballet]. But [John] Cranko, was choreographing. So was Peter Wright? Can’t remember…

Alastair Maculay: Well, those are the years of [Frederick] Ashton also. I know you were in the Raymonda pas de deux in 1962. Were you and anything of his before then?

Donald MacLeary: Oh, yes. I mean, I had done Les Rendezvous with Beryl Grey. She came back to do guest performances, and I did it with her, of course. Ondine? Wasn’t Ondine done then? Yes, Ondine had been put on.

Alastair Maculay: Yes, [19]58, [19]59…

Donald MacLeary: Yes, Ondine I had done, and I had worked. And, actually, occasionally, Fred, when I first joined the big company, occasionally he rehearsed me in the classics.

Alastair Maculay: And now tell me about that, Fred, coaching classics.

Donald MacLeary: Well, I mean, again, very conscious of telling the story and moving. One of the biggest influences to me was Bobby Helpmann. We did a tour of Australia and New Zealand in [19]58, [19]59, and this is the [Royal Ballet] Touring Company, and he danced Hamlet and I did Laertes to his Hamlet. But Lynn Seymour and I were going to do our first full-length. Swan Lake. I had done, like, two with Anna Heaton. We’d learnt it and he [Helpmann] coached us, and he taught me how to be still, how to use my eyes and not to play with props all the time, because you’ll see a lot of dancers who can’t resist using the bow and arrow. And about hearing. You hear with your eyes first and then you look, you know, things like that. Which actors do, you know? Dances don’t always.

Alastair Maculay: Now, you retired from dancing the first time. I think in 197…

Donald MacLeary: Eight [1978].

Alastair Maculay: You were what age then?

Donald MacLeary: 38.

Alastair Maculay: And when you retired, that’s because the body is punishing you…?

Donald MacLeary: Well, I’d had an Achilles tendon operation which went very well, and I was fine. And then Kenneth suddenly said, ‘Desmond Doyle’’ going’ or they gave him the heave-ho, I can’t remember. Would you consider becoming ballet master? He [MacMillan] said, ‘You can go on dancing if you want’. And I went, ‘No, I don’t think I will go on dancing’. And that’s when I became ballet master and I did it for three years. Actually, it was really a bit of a waste of my talent, because anybody can sergeant-major a corps de ballet, but not many people can do [rehearse] the principals. You know, you just you know… and I was doing both. I was doing the whole thing. And I, you know, when… I can remember one of the notators saying, ‘Couldn’t you come to this rehearsal and help [Alfreda] Thorogood, and so and so with this pas de deux in Anastasia?’ and I said, ‘I’ve got to be in here’, you know. So, when I came back, I only coached the principals, really.

Alastair Maculay: And that’s what you feel your best at, as a coach?

Donald MacLeary: Yes. I mean, you know, you can coach lines, but it’s not as rewarding as coaching, and I do enjoy getting people to tell the story. You know, I don’t just go on about technique, I do, you know, to me it’s an art form. It’s not a sport, it’s not gymnastics, it’s, you know, a lot of people can have not a wonderful technique but can still move.

Alastair Maculay: For you, does the story go on in, say, [Marius] Petipa in or [Lev] Ivanov, in Swan Lake through the White Swan pas de deux and through…

Donald MacLeary: Oh yes. I can give you a line for every step, practically. Yeah.

Alastair Maculay: And would that be true also with the wedding pas de deux in The Sleeping Beauty?

Donald MacLeary: Not so much [of] that because you’re celebrating. You know, there’s… the story’s sort of ended, but you’re celebrating something, you know. But, I mean, certainly Swan Lake. You’re telling a story all the time, you know?

Alastair Maculay: One of the roles that changes the most is Albrecht [in Giselle]. I mean, there’s a conventional dilemma: Is he really in love with Giselle or is he just toying with her affections and realises too late that he felt something?

Donald MacLeary: Well, I believe – I mean, I know there is that that theory – but I believe that he was mad about her because he wouldn’t have gone to the grave if it has been a flirtation. He would have said “Oh, it’s a pity she’s gone, but, you know, I’d better keep away.” No, he’s stricken when he comes on in the second act. So, he must have been in love with her. I mean, I played him as being totally sincere…

Alastair Maculay: From the beginning of Act I?

Donald MacLeary: Yeah.

Alastair Maculay: I’m going to end now, but I want to ask you what aspects of your career as a dancer, in particular, you’re most proud of?

Donald MacLeary: I don’t know.

Alastair Maculay: Well, you knew you were a legendary partner?

Donald MacLeary: Yes.

Alastair Maculay: And I think you’re saying you’re proud of always telling a story?

Donald MacLeary: Yeah, I think I’m more proud of the end of my career than when I was actually dancing.

Alastair Maculay: Coaching?

Donald MacLeary: Yeah.

Alastair Maculay: Oh, that’s wonderful. And which dances have you [found] most rewarding to work with?

Donald MacLeary: Well, Darcey [Bussell], Jonathan [Cope] and I can remember Monica [Mason] saying to me once, ‘You must be so proud of Darcey’. And I said, ‘Yes, I am”. And then I said, ‘But it’s the people that were struggling that I’m more proud of.’

Alastair Maculay: That’s true. But also, Darcey is a perfect example because it was easy to mistake the young Darcey for just a brilliant machine, the best equipment in the world. And she became a true artist.

Donald MacLeary: And yes, she did. I mean, she actually… As you said, she did become a very good artist, but she did everything that I ever asked her to do. She never said, you know, ‘I’m not doing that’, and one day, actually, the PR sent me a ‘yellow peril’ saying, would you let the critic from the Telegraph?… I can’t remember what she was called, to watch you rehearse Jonathan and Darcey in Swan Lake? And I went, ‘No’. And she went, ‘Why not?’ And I said, ‘Because when I’m in a rehearsal room, I am telling them all the things that they shouldn’t be doing, and I don’t want the critic to know.’ And she was furious with me, and I said, ‘You know, it’s not their job to come and see the process, they see the end product. I don’t want to give away all their faults. You know, Anthony Dowell said, ‘I hear you haven’t let…’ and I said, ‘Would you have let somebody in when I was rehearsing you?’ And he said, ‘No,’ and I said, ‘There you are’, you know.

The transcript of this podcast may have been lightly edited for ease of reading.