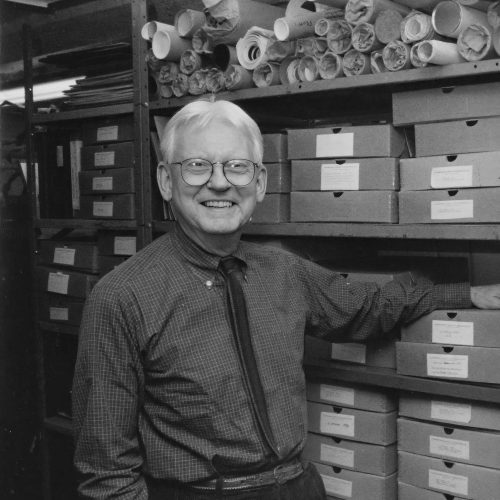

David Vaughan

David Vaughan – unparalleled writer on the choreography of Frederick Ashton – catches moments and movements from The Royal Ballet’s history. In this interview for Voices of British Ballet, which was recorded in New York, he talks to his friend and fellow dance writer Alastair Macaulay.

First published: December 30, 2025

Biography

The archivist, historian and critic David Vaughan was born in London in 1924. He studied at Oxford University and only began dance training after that, in 1947. In 1950 he won a scholarship to study at the School of American Ballet, where he met Merce Cunningham, who was teaching there. Vaughan began studying with Cunningham from the mid 1950s. Later, in 1959, when Cunningham opened his own studio, Vaughan began performing various tasks for Cunningham and the Merce Cunningham Dance Company, including co-ordinating the company’s six-month tour of Europe (with John Cage and Robert Rauschenberg) in 1964. Vaughan became the company’s official archivist in 1976, a post he held until 2012, when the company was disbanded following Cunningham’s death.

In addition to writing and working for and with Cunningham, Vaughan was active in the theatre, film and dance worlds. He acted in off-Broadway productions, devised the choreography for Stanley Kubrick’s film Killer Kiss, and worked on the scripts for films about Cunningham and Cage, and about the choreographer Antony Tudor. Vaughan also appeared in several dance productions, including The Royal Ballet’s revival of Frederick Ashton’s A Wedding Bouquet. In 1988 he wrote an influential op-ed piece in The New York Times, criticising traditional ballet companies for not offering dancers of colour enough opportunities to perform.

David Vaughan was a prolific and well-regarded writer on ballet and dance. His books included The Royal Ballet at Covent Garden (1976), Frederick Ashton and His Ballets (1977, revised edition 1999) and Merce Cunningham: Fifty Years (1996). He contributed frequently to the Dancing Times magazine, and with Mary Clarke he also edited and contributed to The Encyclopaedia of Ballet and Dance (1980). In 2015 David Vaughan received a Dance Magazine award. He died in New York City in 2017.

Transcript

in conversation with Alastair Macaulay

Alastair Macaulay: David, I thought we’d try starting with some images of movement, because you have this memory. We were talking about [Margot Fonteyn as] the Woman in a Ball Dress in [Frederick Ashton’s] Apparitions, and you said, “Oh, I’ll never forget her waving her fan, moving her upper body.” Why did that matter?

David Vaughan: Well, because it was actually – for one thing – it was very musical, what she did. It was the Valse Oubliée of [the composer Franz] Liszt, and it was the moment in the piece when the waltz theme comes up, after the first two apparitions are the monk and the hussar, who, as far as I remember, in their windows just stood, but she was the one who moved and fluttered the fan up and down. She was very seductive, and it did conjure up the idea of there being a ballroom where people were dancing. So, it was a dance moment, in other words, even though she was just in one spot, behind the window.

Alastair Macaulay: I know we are going to talk about movement, but I nonetheless find myself wanting to ask you more about Apparitions, because I know you loved it so, and miss it. Some people said it was better in the old days when it was [performed at] either Sadler’s Wells, or the New Theatre than when it came to Covent Garden.

David Vaughan Oh yes, absolutely.

Alastair Macaulay: Was that to do with just the size of the stage? I think some people also say that once Fonteyn was older, she…

David Vaughan Yes. Also, [Cecil] Beaton redesigned her costume, instead of the, sort of, lavender ballgown she had in the original with some decoration on the skirt of a mask, or flowers, or something, at Covent Garden she wore this rather elaborate, dark colour, maybe black, or black and mauve. The whole thing was much more sophisticated from what she [originally] did.

The thing was, as Clive [Barnes] actually wrote wonderfully about her in the original, that she was a young girl, but still very seductive, in the original. I mean, he [Beaton] kept the basic idea of the design, that there was a wall on one side, and wings on the other, and people would appear… dancers would appear and disappear in and out of the wings, and there were shadows on the backcloth, and probably on the wall side, of musical instruments. A cello, or something, so that the idea of the ballroom was very, like a dreamlike scene. There was a lot of stillness in the choreography, in terms of the corps de ballet, who would keep static poses while the woman and the poet moved among them.

Alastair Macaulay: I know you wrote, after the last revival of Apparitions, “At least they should try to keep the ballroom scene alive”.

David Vaughan: Yes, absolutely. I think that was one of Ashton’s masterpieces of that period. I mean, the second scene, the corps de ballet, with the bells, was a very complex piece of choreography rather foreshadowing what he did with the corps de ballet in Scènes de ballet, I think

Alastair Macaulay: Because of geometries, or timing, or what?

David Vaughan: Yes, with sharp movements up and down, and head turning… the head, and so on. And then there followed the funeral procession in which a figure was carried on a bier, and [it] turned out to be, I think, the figure of the woman lying as though dead. And that was… actually, it was quite scary. And then the third scene was the sort of diabolical orgy, or something, where she appears with a hideous mask, you know. And that was to the third Mephisto Waltz, and the problem with that was that the music was a little long. Ashton had to keep going, you know, and, actually, they made cuts in it, I think, when they revived it at Covent Garden.

Alastair Macaulay: OK, jump to another image. You always remember the amazement of the performance of [La] Boutique fantasque at Covent Garden, when suddenly on came these legendary Diaghilev dancers, [Léonide] Massine himself, and [Alexandra] Danilova.

David Vaughan: I don’t know what it was. You just had this surge of excitement that you saw what it must have been like in the old days with those two coming on. I mean, they were motionless, they were brought in on a little trolley, you know, and he’s perhaps kneeling in front of her, and she’s holding a pose. I mean, once they started to dance, it was a little disappointing, because they couldn’t, you know, they couldn’t hold their legs up the way they were supposed to do, but just that one moment, it was just breathtakingly exciting.

Alastair Macaulay: You used to write about something called “Royal Ballet fever”, particularly in the 1960s and the 1970s when New York balletomanes just sold out the Met [Metropolitan Opera House]. The Royal came every other year, sometimes consecutive years, once for eight weeks in New York. More than once it did five-month tours of America.

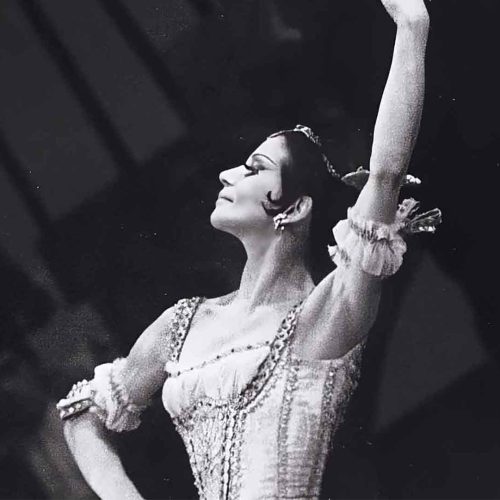

David Vaughan: Well, of course, a lot of it was due to the presence of Margot and Rudi [Rudolf Nureyev]. I mean, when they did Fille the first time, they had to put on [the “Shades” scene from La] Bayadère with it, otherwise they wouldn’t have sold tickets, because La Fille mal gardée was a ballet nobody knew. I mean, it didn’t mean anything to them.

Alastair Macaulay: But apart from Margot and Rudolf, there were other dancers who reached their peak in New York.

David Vaughan: Well, yes. Early on there was [Lynn] Seymour, you know, the great dramatic ballerina that everybody wanted to see her do Juliet. And, of course, she did a wonderful Giselle at a matinée, which was extraordinary. I remember Carolyn met her at a party, or something, and said how wonderful it was. Carolyn Brown [of the Merce Cunningham Dance Company] I’m talking about, and Seymour said, “You know, nobody in the company, in the high up of the company, said anything to me about that performance afterwards”.

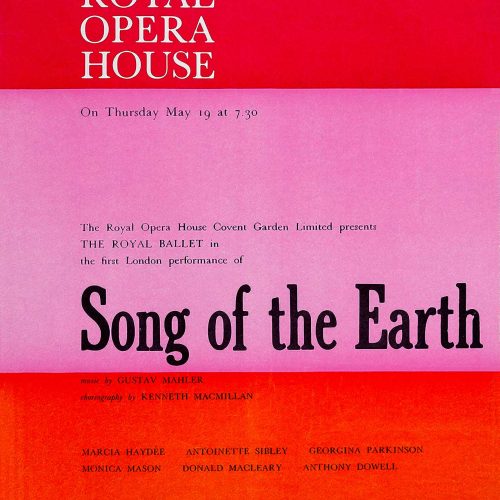

Alastair Macaulay: Another couple who reached their peak in New York was [Antoinette] Sibley and [Anthony] Dowell.

David Vaughan: Absolutely.

Alastair Macaulay: What ballets do you particularly remember them in?

David Vaughan: The Dream. Especially The Dream because, I think I’d read some reviews from London which were very lukewarm about the ballet, and we all went to see it, and there was this masterpiece, you know. And especially with those two. Fred really made that happen, I think, and especially in that ballet, and then it went on into Swan Lake, especially.

Alastair Macaulay: You mentioned that The Dream was immediately more admired in New York, and that comes up in your book, that it was often New York that made people pay attention to the greatness of certain Ashton ballets. I imagined when I was reading your book that you had come across that by researching and reading the reviews but, actually, you are talking about The Dream as if you absolutely were aware of it at the time. You’d read the British views and thought, “Oh, no, they’ve underrated this”.

David Vaughan: Well, and Daphnis [and Chloë] too, I think, and of course…

Alastair Macaulay: You first saw Daphnis here, in New York?

David Vaughan: Yes. Yes, with Margot and Michael [Somes], and, I mean, the original cast, and then the next cast of Daphnis, from the Royal, was of course Sibley and Dowell, which was a wonderful cast.

Alastair Macaulay: We’ve touched on Nureyev. Perhaps we should talk about the changes in male dance rs you’ve seen over the years.

David Vaughan: Right.

Alastair Macaulay: I mean, first of all, two men I… well, I did see a little [of Robert] Helpmann but tell me about Helpmann and [Anton] Dolin in princely roles.

David Vaughan: Well, I think Dolin was a better technician than Helpmann ever was, probably, but Helpmann and Dolin were both wonderful partners, and Helpmann, you know, was a great theatre person. He could always fake anything he had to do. I mean, there was… I remember at the New Theatre once [during World War Two] when they were really suffering [the] loss of men, and Helpmann had to do the Blue Boy in [Les] Patineurs, and he had, you know, he faked it, but I don’t think many people in the audience felt it was being faked. But the big difference Nureyev made to the men, apart from, you know, the example of someone who was a strong personality, and so forth, but Nureyev was a nut about technique. And something you saw maybe for the first time in the Royal [Ballet] men was, you know, good fifth positions [of the feet]. I mean, there’s that film that we have now, of Michael Somes and Fonteyn doing the Petipa ballets. You know, he’s never any good [in] fifth position. When he does a pirouette, I mean, he doesn’t do it even from a good fourth [position]. I mean, he just put his foot down and turned, and there was no feeling of the technique of the turn.

Alastair Macaulay: Did that seem striking at the time? Were there men who made you think, “Oh, Michael’s lucky”?

David Vaughan: Well, I think maybe I didn’t put it in those terms, but certainly, you know, I probably felt that Nureyev was more precise technically than we’d seen and then, of course, the effect on other male dancers of the company was very strong. On people like David Blair, Michael Coleman, that, you know, they really polished up their technique in a way they hadn’t perhaps before.

Alastair Macaulay: At some point we achieve the extraordinary definition of British classical male star that is Anthony Dowell, which is a kind of standard to this day that is admired. One of its amazing characteristics is the extended line in arabesque, often in fondu.

David Vaughan: You know, there was always that sense that a man doesn’t do a full extension – that’s not masculine enough. But with Dowell, for the first time, you saw that beauty of line was still what a male dancer should have. I mean, and looking the other day at, you know… [Herman] Cornejo was in the ballet the other day, and again, you know, that’s a more classical role in the sense than Puck, but again, his wonderful extension, the wonderful way he fills out the line. Yes, and Dowell had that kind of quality. I think that was something missing.

Alastair Macaulay: I think [the teacher] Richard Gladstone said that when he came along to The Royal [Ballet] School, it was considered effeminate for a man to rest his foot on the barre. Men don’t do that.

David Vaughan: Probably, yes.

Alastair Macaulay: And he said of course that changed. But he tells a story, this is, sort of, the post-Dowell generation, that I think, in the mid 1970s, 1975 or something, they did an exchange, one of their best boys with one of the best boys at the Paris Opéra [Ballet School], and they sent Stephen Beagley over to the Paris Opéra. And the French gave notes when they came back, and said, “You know, you should give him more barre work. You should have his leg up at the barre.” Six years later, they sent over Phillip Broomhead, and the French were saying, “Enough already. He’s doing too much extension”.

David Vaughan: Yes, yes, right. Right, yes, yes. Phillip Broomhead was a bit too much, but I remember when I was, you know, I went back to England after I’d been studying at the American school, and in class one day I think, you know, when we did grands battements, I lifted my leg a little higher than perhaps I normally would have, and another guy said, “Oh yes, well, you’ve been studying in America.” So, you know, that’s what they do in America, they go for the extension, and we don’t do that because… yes.

Alastair Macaulay: One of the things that’s changed in my time, let alone yours, is hips. The Royal [Ballet] hips, in particular, used to be the most level hips in the world. That changed during the late 1970s and 1980s. Did that bother you?

David Vaughan: Somewhat, yes. Yes, because I… well, [Audrey] de Vos, you know, as a teacher was very insistent that you didn’t lift the hips, but that was not only true in England. I mean, Carolyn Brown tells the story, when she auditioned for Jerry [Jerome] Robbins for something, and, Jerry said, “Can you lift your leg higher?” And Carolyn said, “Well, I have to shift the hip,” and he said, “Well, shift the hip, then”.

Alastair Macaulay: That’s because she’d been studying with [Margaret] Craske and [Antony] Tudor. You know, Cecchetti [method] teachers in New York.

David Vaughan: Yes, yes.

The transcript of this podcast may have been lightly edited for ease of reading.