By Stephen Johnson, composer, writer and broadcaster

Diaghilev – genius or promoter of self? In addition to being central or crucial to the history of ballet in the 20th Century, Diaghilev was also intimately involved with musical developments of the time.

‘Improvement’, wrote William Blake, ‘makes strait roads, but the crooked roads without improvement, are the roads of Genius.’ Was Sergei Diaghilev a ‘genius’? I’ve met people, knowledgeable people, who protest that he wasn’t. He was a highly-effective talent-spotter, they argue, an ingenious synthesizer of others’ skills; but if he had a talent of his own, wasn’t it simply for delegation – that, and an unabashed flair for self-promotion?

Even if that were true, as a musician one fact stands out for me like a blinding light. Look at the number of twentieth century ballet scores that have become regulars in the concert hall – not just in selected and edited ‘suites’, but also as complete self-standing ‘works’ in their own right. An astonishing number of them were Diaghilev commissions. To take only the ones heard entire, as composed for Diaghilev, there are Debussy’s Jeux, Ravel’s Daphnis & Chloe, Satie’s Parade, Falla’s The Three-Cornered Hat, not to mention five of the greatest (some would say the greatest) Stravinsky ballet scores: The Firebird, Petrushka, The Rite of Spring, Les Noces, Pulcinella. Not only are they widely popular and much-admired today, a century after they were composed, but the Debussy, the Ravel and all five of the Stravinskys are seminal works, exerting a huge influence on the development of music as an art in its own right. Doesn’t this alone indicate that even if Diaghilev was just a talent-spotter, he has a right to be considered a talent-spotter of genius?

Blake’s comment about ‘crooked roads’ provides a helpful shaft of light. Look in most small reference books and you will commonly find Diaghilev credited as a ‘ballet impresario’, fairly often with the words ‘great’ or ‘greatness’ lurking somewhere in the background. In all probability the imagination will start to construct a brief speculative biography: a sensitive Russian boy with a highly developed imagination is taken to the court theatre at an impressionable age, is entranced and bowled over, and conceives a dream. Perhaps the dream requires a little modification: it’s soon clear that he won’t become a dancer – but to create ballets… And from that small but potent seed a colossal, luxuriant tree grows, providing shelter and nourishment for a wide range of exotic and wonderful creatures: dancers, choreographers, designers and, of course, composers.

In fact the road to the Ballets Russes was much more crooked than that. Young Sergei’s first dream, or the first one that consolidated into a sustained ambition, was to become a composer. At an early age he was given piano and singing lessons, and it soon became clear that he had a significant talent. A little later he composed a song, or ‘romance’, the style of the father-figure of Russian musical nationalism, Mikhail Glinka, entitled Do you remember, Maria?, the manuscript carefully preserved by his beloved stepmother. Poignantly it is Diaghilev’s only known surviving composition, but more were to follow. When the previously prosperous Diaghilev family fell on hard times, Sergei agreed to follow the practical career option of studying law at St Petersburg University, but increasingly he gravitated towards the world-famous Conservatory of Music, where he graduated in 1892, aged twenty.

Typically, Diaghilev threw himself into St Petersburg’s high-end musical life, becoming a regular at the most prestigious musical soirées, acquainting himself with the works of the famous ‘Mighty Handful’, or ‘Russian Five’, prominent amongst them Mussorgsky, Borodin and Rimsky-Korsakov. He conceived a passion for Tchaikovsky, and news of the latter’s surprisingly premature death in 1893 shook him profoundly, apparently leaving its mark on the violin sonata he was writing at the time. ‘If I were to give it a name,’ Diaghilev wrote, ‘it would be something like this: “The death of Tchaikovsky in particular and the death of all people in general”.’ (Death was to be lifelong morbid obsession for Diaghilev, as it had been for Tchaikovsky.) At the same time, he was nurturing a secret veneration for the music and ideas of Wagner – secret because Wagner was dirty word for many nationalists in Russia at that time. Here perhaps we get a clearer indication of the kind of ‘genius’ Diaghilev was to become. For Wagner, music could not exist fully on its own, as an art-form in its own right. The splitting of the arts into separate life-forms was sign of the rot at the heart of the development of Western civilization. What was needed was a bringing together again, a ‘total work of art’ (Gesamtkunstwerk).

If that provided one pointer along the crooked road, so soon did another more devastating one. In great excitement Diaghilev took his manuscripts to Rimsky-Korsakov, then widely regarded as the outstanding composition teacher in Russia. The encounter was recorded by one of Rimsky’s closest friends, Vasily Yastrebsky. Apparently Rimsky told him how he had been visited by ‘some young man named Diaghilev, who fancies himself a great composer.’ Rimsky pronounced Diaghilev’s efforts ‘absurd’, whereupon Diaghilev swept grandly from the room, informing Rimsky that his verdict would come to occupy a shameful place in his biography and make him repent his rash words, but by then, of course it would be too late! But despite his defiance, Diaghilev was crushed, and the dream died.

Was Rimsky right? It’s worth noting that Rimsky also failed to spot the budding genius of his pupil Igor Stravinsky (despite what the latter subsequently claimed). Diaghilev’s realisation that he had seen what Rimsky hadn’t, and in the process effectively launched the career of one of the century’s musical Titans, must have given him satisfaction. So too must the vehement public protests of Rimsky’s widow, more than a decade later, when Diaghilev staged his own ballet production of Rimsky’s hugely popular tone poem Sheherazade. Diaghilev’s next step along his circuitous road (after a period of desolate self-questioning) was to try to reinvent himself as an art connoisseur, in which he eventually had some success. The lasting beneficial effect of that can be appreciated in accounts of the sheer visual spectacle of the Ballets Russes’s landmark productions. But as Diaghilev’s Finnish near-contemporary, the composer Jean Sibelius, was to come to realise, it is often from failures and broken dreams that the finest and most lasting achievements grow.

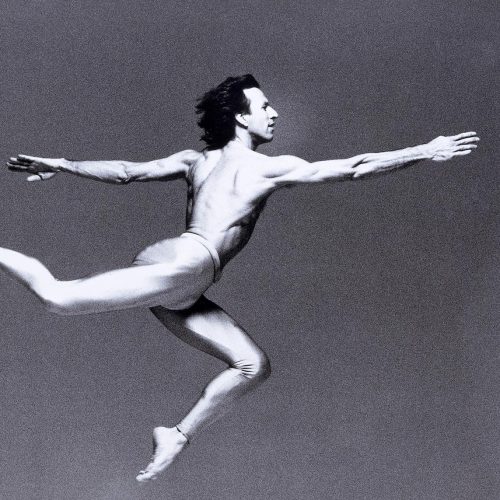

And so we have those extraordinary ballet scores. How much Diaghilev communicated specific suggestions and requests isn’t always easy to tell: understandably composers like to cover their tracks when it comes to acknowledging the input of others into ‘their’ creative work. And Diaghilev’s overbearing, Svengali-like character does seem to have had the effect of making his some of his protégés want to downplay his influence in retrospect. It’s quite possible that some of them read his desires and expectations by a kind of mental osmosis, rather like the mysterious way some great conductors have immediately changed the sound an orchestra made just by stepping onto the platform – there are several trustworthy accounts of the legendary Wilhelm Furtwängler having exactly that effect. Reading Stravinsky’s accounts of his breakthrough collaboration with Diaghilev on Firebird, however, one notes the keen interest Diaghilev took in the appearance of Stravinsky’s sketches on the piano stand, and his concern to involve Stravinsky in the practical processes of preparing the epochal first performance in 1910. Playing the piano for the dancers in rehearsal Stravinsky clearly learned a great deal about how the human body moves, and how music can prompt it to even greater heights of agility and expressive elegance. So many of Stravinsky’s scores from Firebird onwards – including those written purely for the concert hall – manifest an extraordinary flair for ‘sprung’ rhythms, the kind of rhythms you can’t hear without wanting in some way to move along with them.

Rhythm is such a feature of the classic Diaghilev scores that it’s hard to believe he wasn’t in some way its presiding genius. With his Wagner-enhanced feeling for the melodic and rhythmic patterns of speech, and of how they mark the character of a culture’s folk music – so vitally and vibrantly in the case of Russian folk music – Diaghilev clearly communicated something similar to his composers. Stravinsky’s music pre-Firebird shows no special flair for rhythm – in fact it can be rather foursquare. But there, in the climactic dance for Kashchei, are those amazing pounding, heart-stoppingly asymmetrical dance patterns that seem to yank the dancers up and twist and jerk them around like puppets. The astonishing, elemental rhythmic innovations of The Rite of Spring, which three years later was to explode like a bomb on a stunned Paris, were surely conceived here. If it had just been Stravinsky then Diaghilev’s putative influence could perhaps be discounted. But what about the weird dissociative games Debussy plays with his basic waltz-tempo in Jeux, not like anything he’d ever done before; and what about the most un-Ravel-like Dionysian 5/4 dance that ends Daphnis and Chloe, premiered the year before The Rite of Spring? Knowing that there were dancers who could dance to this sort of thing would have been an encouragement – perhaps. Even so the Ballet Russes troupe found they could only cope with Ravel’s alarming metrical patterns by chanting Ser-gei-dia-ghi-lev along to the music. Even in the basic pulse, Diaghilev’s name was imprinted on the music.

Diaghilev’s early involvement with the most progressively-minded musical circles in St Petersburg, and later at Wagner’s Bayreuth and in radical-chic Paris, also clearly helped him understand something else: the titillating appeal of the appetisingly shocking novelty. Nothing set the tills ringing like a scandal – as Richard Strauss had recently discovered after the sensational shock-impact premiere of his opera Salome. ‘Salome will do Strauss a lot of damage!’ opined the Kaiser; ‘So much damage’, Strauss observed wryly, ‘that with the takings I was able to build my villa at Garmisch.’ Where better in the world to exploit the success de scandale than in the city that gave the world that very phrase, Paris. And when Paris threw up its exquisite hands in delighted horror, the rest of the world, slowly but surely, would follow. At all costs avoid getting stuck in a rut: so when people come to expect the perfumed exoticism of Firebird, give them the spit-sawdust-and-vodka-fume realism of Petrushka; when they’ve just about accustomed themselves to the ear-splitting dissonances of Rite of Spring, give them the faux-naivety and absurdity (foghorns, gunshots and musical typewriters thrown in) of Satie’s Parade; and then, when they think they’re prepared for anything, give them the half-ironic, half-affectionate eighteenth-century parody of Stravinsky’s Pulcinella – in the process launching Stravinsky’s equally notorious ‘neo-classical’ period. Should Diaghilev be given major credit for that too? It would appear so.

Above all there was his love of opulence, of spectacle, of luxury: ‘You want an orchestra with a hundred players? Leave it to me.’ And there’s something else that Diaghilev must have realised, if only intuitively, something that often gets forgotten in histories of the major developments in twentieth century music. The list of hugely influential and hugely popular innovative Diaghilev scores – to which the names of Prokofiev, Poulenc and Respighi should also be added – reminds us something important which often gets forgotten by today’s new music champions: challenging new musical ideas go down a lot better when they’re helped by a good story and plenty of strong visual aids. (Pop video producers have known that for a long time.) Perhaps once again Diaghilev has something to important to teach composers and promoters, something we need to hear.