By Caroline Southam (Caroline Emo), dancer

Outreach and Accessibility dominate in recent times, but Peter Brinson’s Ballet for All was way ahead of its time in this respect.

My tour with Ballet for All in 1967 is a map with gaps: gaps in the map of England, in my letters home, and above all in my memories. I do know that it was a happy time, a young time, spring was turning into summer in the gentle English countryside that we saw from our coach, from the horses we rode on a Northumbrian moor, from a picnic in a field near St Neots, from a river boat at Worcester. Our passage through villages and market towns like Claverdon and Alcester had a soothing effect on our high-strung dancer spirits, and in “this green and pleasant land” we learnt to shake off our nostalgia for London.

I only have three letters to help me remember. The first two, from York and Newcastle, are on Arcady Blue writing paper, the third, from Worcester, on Cornish Blue. This switch wasn’t painless; I was very attached to discreet, dusty blue Arcady that I had started using on my first tour with the Royal Ballet, but it was discontinued. Later I became as attached to Cornish, a rich almost royal blue, now also long since discontinued, as indeed is the practice of letter-writing. But in those touring days in the sixties, the sight of familiar handwriting on an envelope at the stage door brought comfort, and I know my parents longed for the twice weekly arrival of the blue envelopes.

The contents were often far from joyful, but there is a rare lightness of tone in these Ballet for All letters. No real picture of the time emerges from them, but perhaps the most significant reference is to “this ghastly war”, written on 6th June, in Worcester, the day after the Six Day War began. Other clues come from my buying a Dollyrockers dress, and the films we saw: Zeffirelli’s La Bohème with wonderful Mirella Freni who died in February 2020, and Privilege with pop star Paul Jones and the gorgeous model Jean Shrimpton. I wrote a little review for my parents, which I now feel could be summed up by “this ghastly film”, but instead I ended it with “quite an interesting film, if horrifying in a Brave New World manner”. I had read the book not long before and it had made a deep impression on me.

The places I know we danced in are York, Newcastle, Chester, Worcester, Norwich and Kidderminster, but the tour must have included other venues which I cannot remember. I have no record of Kidderminster, but the name stuck in my mind , while a press cutting confirms that we took part in the Triennial Festival in Norwich, dancing in the hall of the Heartsease Secondary Modern School. I make a reference to Chester and to a “very touching letter” I received from Betty Hassall of the famous Hammond School.

Our miniature company was a close-knit group, and I forged a special friendship with Maggie Lorraine that has stood the test of time and distance, as I knew at once when I saw her, apparently unchanged with her wide trusting eyes, a couple of years ago in London. On our tour she was an enchanting Lise in Fille, and her touching Giselle welled up from within her. The “boys” were fun: my nice partner, Spencer Parker, and dear Alan Hooper, whom I had known since he was in shorts at White Lodge, two forms below me. Sixteen years later, just before his tragic death, he asked me to become the RAD Organiser in Italy, a taxing job that I took on for a year, out of affection and loyalty.

There was an essential feel about Ballet for All, the performing art of ballet condensed to four “principals” with no corps de ballet, a piano instead of an orchestra, one ballet master, one wardrobe mistress, a stage manager but no touring stagehands, a driver. And our lynchpin, the actor Roger Hume, in my mind forever Théophile Gautier. Roger metaphorically enfolded us jittery dancers in the great cloak he wore, imparting some of his deep solidity and giving us the confidence to “get up on that stage and do it”. The bond with Roger was very strong and I have kept one letter of his, written some years later; I don’t need to open it to remember the address.

Of the letters home that I still have, the first was written from York, in May 1967, and tells about our rehearsals for the York Gala at the Theatre Royal. Alongside our Ballet for All programme, there appears to have been a special performance of a new ballet, Mogadon, by the choreologist Faith Worth, which was making everyone very fraught, because the costumes were impossible to dance in and the designer also wanted the dancers, Pat Ruanne and Shirley Grahame, to wear goggles which blinded them. To compound all our troubles, the stage had a bad rake. I had a “little weep” after feeling “completely spastic” rehearsing the White Swan variation, “Maggie was in despair” (she must have been dancing Giselle or Lise), “Pat had tears and Shirley was the only calm person in the dressing-room”.

What a privilege to have been in the same dressing-room as these two artists, Shirley so perfectly slender with her clear, peculiarly English line, and Pat, fluid, sensuous, expressive, relaxed in her body, only two years older than me, but a woman, not a girl. I can still remember her backstage, with the Company, preparing in the wings with just a few fondus. She never did a real warm-up, because she said it made her tense and nervous. A fondu, both in name and action, fitted Patty perfectly.

Our gala performance in the end “went off pretty well”. The ballerinas were laden with bouquets and Maggie and I each received “an enchanting posy”. Piers Beaumont was also present and I commend his dancing, but don’t say in what piece.

I was sorry to leave York and its beautiful Minster. There had been time to go to a party given by the house manager of the Theatre Royal and to visit the York Art Gallery which I condemn as being ”not good by provincial standards”, evidently after nearly three years on tour I considered myself an expert!

Our next venue was Newcastle, where we performed, in “rough conditions”, in Heaton Grammar School. On looking it up now, I find that one of the school’s better-known old boys, bass player Chas Chandler, had brought Jimi Hendrix to his home in Heaton just a few months before we danced there, our arrival was surely less exciting! We did the Lac programme and I myself was in a fairly rough condition, saddle-sore from an afternoon’s riding the day before. I can still remember the agony, in class, of grand plié in second position, and of extensions. In my mind’s eye I can see Oliver Symons’ quizzical smile, Olly our tolerant, good-natured ballet master. At the piano would have been stalwart Jonathan Frank, who was probably looking forwards to his dinner, which was always the same: soup, chicken and fruit salad – tinned, as I recall! Later in the tour he was replaced by Michael (possible surname Hyatt), who was much younger, dark-haired and white skinned, a pleasant personality.

Five of us had set forth in the coach the previous day, a Sunday, to Corbridge-on-Tyne, my birthplace. Maggie had, very wisely, opted out. With me were Alan, Spencer and our wardrobe mistress Lynn Prosser, who later became his wife, and we were driven by red-haired Tom Gardner, a dear companion throughout the tour who made me “have faith in myself as a dancer and will not let me consider defeat”. Oddly enough I say nothing about the emotions of returning to Corbridge, where my grandmother had lived and where I was born in 1946, though I only stayed there about five weeks, before flying out to Greece with my mother, to spend my infancy in Athens.

I do write about the “crazy thing” and “super fun” of our ride (I on a grey horse) and about the “pure hell” of trotting, followed by the relief of a canter. I also mention my fondness for the lovely Northumbrian countryside, wide and generous to the eye, which remains to this day. After dismounting we had tea in the village, Alan bought a Victorian print for £8, Tom and I went into the Saxon church of St. Andrews where I was christened. We wanted to stay for evensong, but when we went in search of the others, they were sitting expectantly in the coach!

My next, and last, letter is from Worcester, written on 6th June. On the way there (from Cambridge or Norwich), we had passed through Southam and I have a photograph of my smiling self leaning on the signpost at the entrance to the small market town.

Aside from my worry over the outbreak of the Six Day War, I very much enjoyed Worcester. I explored the town, admiring the old black and white houses, especially 15th century Greyfriars, and in an antique shop I bought myself a pair of Royal Worcester cups and saucers, gorgeously decorated in about 1880 with golden birds and butterflies, which I treasure today.

The Swan Theatre was near the river with a large stage and “super dressing-rooms”. At a matinée I did “I think, the best ‘Lac’ I have ever done”.

The extraordinary thing about Ballet for All was that we young dancers were entrusted with the great ballerina roles, albeit in potted form: Odette/Odile and La Sylphide (which fell to me), Giselle and Lise (Maggie). This had seemed so entirely possible, indeed probable, to my six-year old self, had remained a dream at the age of ten when I joined the Royal Ballet School and was reading Veronica at the Wells, but a progressive awareness of my unsuspected limits soon put my ambitions in perspective, and what a harsh awakening that was.

However on this tour, for a few weeks, I did step into ballerina shoes. I was no Odile, for I lacked glitter, glamour, and seductiveness, but I had some affinity with lyrical Odette and loved the Act II Variation which I approached like a priestess, something no mature artist would do. I tried very hard to describe Tchaikovsky’s music with my movements, lifting arms, leg and soul with him, sinking through the foot with him, dispensing serenity, until that last urgent diagonal. It was a brave attempt.

Unfortunately, at that time I hadn’t yet had the benefit of Miss Edwards’s private lessons, which revolutionised my approach and my technique. A year or two later she did me the great honour of selecting me for weekly sessions in the little Practice Room in Talgarth Road. From the first few I emerged in tears of despair, but gradually I found I was changing from the inside out, a completely new sensation. This was physical; had I found the way to accompany it with a similar transformation of my psyche, I might have continued doing what I loved most for a few more years.

I was no Bournonville dancer, but I was deeply grateful for the chance to interpret the poignant role of La Sylphide; it became my favourite. At one performance, there were tears on down-to-earth Spencer’s cheeks as I blindly felt them; after half a century I can still trace in myself something of the long-buried emotions that bound us, artistically speaking, in that moment.

In Worcester Maggie and I were interviewed “for the woman’s page of the local rag”. I have the article, in which we both talk about our dedication, our aspirations and our hopes that we would not have to choose between a career and marriage. Maggie is “a petite brunette with eyes as round as saucers”, I am “a slender girl with classical features who bears, I’m told, an uncanny resemblance to the first Sylphide, Marie Taglioni”. The journalist must have been talking to Peter Brinson, creator and head of Ballet for All, distinguished, knowledgeable, highly intelligent, with a good sense of humour. Whenever he appeared at one of our venues he lent a touch of class to our little company! Peter was admirably far-sighted, sowing the seeds for future ballet audiences with these programmes that brought our rarefied world to audiences unschooled in the arts, especially ballet. When I had first heard I was to go out on the tour I was dismayed at the prospect of exile from the main Company, but very soon I took pride in our mission and the freckled, starry-eyed twelve year old girl in Heaton Grammar School was as important to me as the fan with flowers outside a more metropolitan stage door.

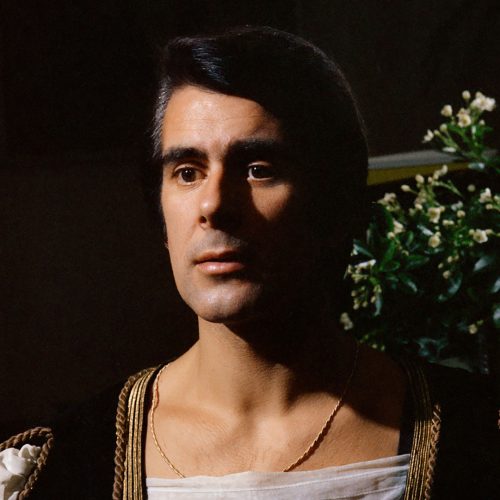

Peter got it into his head that I resembled Taglioni and went so far as to insist to my parents, when they met him, that I should have my portrait painted in the Sylphide wreath, which he offered to lend us for this purpose. I was reluctant, my parents delighted and they immediately commissioned the portrait from John Ward R.A., who a little later was to teach Prince Charles sketching and water colour technique.

The painting is dated 1968. I cannot now recall whether my sittings at the Royal Academy in Burlington House were for some reason a whole year after the end of the Ballet for All tour, or whether Ward was slow in completing his work. I remember he told me we were in the Sitter’s Room, but I can find no confirmation of this description. The walls were of dark red damask and I stood in front of a large painting by either Gainsborough or Reynolds. Ward was very affable and later he gushingly wrote to my parents that “painting Caroline was bliss”. The short letter, written from his home, Bilting House, on 15th June 1968, is inserted into a delightful water colour sketch of the Forum in Rome, where he had just spent some days in “delicious inaction”. This hangs in my house as does a Chalon print of Taglioni in an arabesque poised for flight, which I was given in June 1967 by a family friend, the publisher Bernard Stone. Her airy grace, pearls and blue satin ballet slippers are enchanting!

My very special experience on Ballet for All came to an end in the summer of 1967. I cannot say it was unforgettable, because I have forgotten so much, but I do know that it was greatly significant at the time and that I felt deep regret when the little family I had come to love dispersed for the holidays, I to Paris for my memorable twenty-first birthday.