Marcia Haydée

In April 2017, Marcia Haydée was in Stuttgart for a week to celebrate her 80th birthday. Patricia Linton, founder and director of Voices of British Ballet, knew this was her only opportunity to see Haydée in Europe, so she telephoned Stuttgart Ballet to see if she could interview her. Patricia takes up the story in her own words: “They listened to my request, and, in perfect English, said they would ask Miss Haydée. With a full schedule of rehearsals all week, Marcia said she was free on Thursday from 3.30pm to 4.30pm. She didn’t know me at all, but it was enough for her to know how much I loved Kenneth MacMillan’s ballet, Song of the Earth. So, I jumped on a plane…This is the extraordinary Marcia Haydée…”

In the interview Haydée explains how she was aware of both John Cranko and Kenneth MacMillan as a student at the Sadler’s Wells (now Royal) Ballet School, without suspecting her later close involvement with both men. In working with them, Cranko came to appreciate her melding of a Russian and a British approach to dancing; MacMillan was demanding and uncompromising, but she always strove to fulfil his requirements. She speaks revealingly about working in Stuttgart with Cranko on Onegin and with MacMillan on Song of the Earth and suggests that in those days and in those works, dancers took things at a speed and with risks that today’s dancers, for all their qualities, do not attempt to emulate. The interview is introduced by Dame Monica Mason.

First published: December 9, 2025

Biography

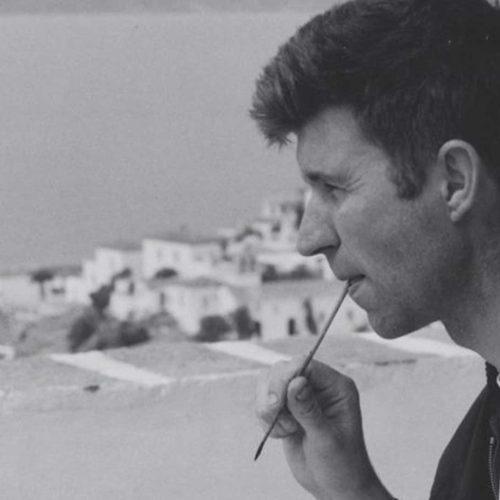

Marcia Haydée is a Brazilian-born ballerina, choreographer and company director. She was born in Rio de Janeiro in 1937, and after studying in Brazil, came to the Sadler’s Wells (now Royal) Ballet School in London in 1954, joining the Grand Ballet du Marquis de Cuevas in Monaco in 1957.

Haydée joined the Stuttgart Ballet in 1961 and was named prima ballerina the following year by the company’s director and choreographer, John Cranko. Their relationship – her dancing, his choreography – was to become the foundation of Stuttgart Ballet’s international reputation in works such as Onegin, Romeo and Juliet and The Taming of the Shrew, among many others. She also worked closely with Kenneth MacMillan on works such as Las Hermanas, Miss Julie and, above all, his Song of the Earth and Requiem. In 1976, she became director of the Stuttgart Ballet, a position she held until 1996. During her dancing career she performed as a guest artist for notable ballet companies throughout the world.

From 1992 until 1996 Haydée directed the Ballet de Santiago de Chile, and again from 2003 until 2004. Since retiring from performing she has pursued a career as a choreographer, teacher and coach, and she also stages many ballets.

Transcript

in conversation with Patricia Linton

Patricia Linton: You were a student at The Royal Ballet School?

Marcia Haydée: Yes.

Patricia Linton: In the mid 1950s?

Marcia Haydée: Exactly. And then when I was a student in The Royal Ballet was when I saw first the ballets from [John] Cranko, and I saw [Kenneth] MacMillan still dancing. MacMillan was doing [The] Lady and the Fool.

Patricia Linton: And did you have a feeling for Cranko’s ballets even then?

Marcia Haydée: Well, I loved [them]. I remember that my favourite was The Shadow that he did for Svetlana Beriosova with Philip Chatfield. So, yes, but it never, never came in my mind that one day I was going to work with both of them, Kenneth and John.

At that time, [at] the School, you really could see the English schooling – the footwork was very, very clear, very important. Instead, with the Russian school that I had [been trained in], everything was more on the top, the back, the arms, the head. And there, when I went to the Sadler’s Wells [now Royal Ballet School], I had to really work on the bottom part [of the body], and that was very good [for] me. I had two, two and a half years that I really learned a lot, so I had the best from both Schools, and then a mixture of both; that’s what made me. I think that’s one of the things that Cranko liked, with me, is that I wasn’t stuck in one style, and with Cranko he really used to say I want my dancers to be able to work with any choreographer that comes, so that means you must not be stuck in one style.

Patricia Linton: What did you see in each other? What was so special?

Marcia Haydée: We connected from the first moment. He was a fantastic choreographer, but as a teacher he was choreographing the class. So, sometimes he used to put steps together that really you needed weeks of work to be able to do it. And there was the first class that I did with him, and he did a diagonal, and [the] diagonal he showed, “I want this and this and this and this and this and this”. And he says, “OK, start”, and nobody had understood anything. So, he said, “Come on, somebody start.” And I was doing the audition; I put myself in and I went, and that was the moment because he saw that I understood him. It’s not that I did [it] perfect[ly], but I knew what he wanted to do; I knew what he had in his head. When he choreographed for me, I could read what he wanted, and if he did one gesture, I understood what he wanted to do, and that’s why I became his dancer.

And now, my situation now is that when I come here [to Stuttgart Ballet] I always tell the dancers how it was to work with John, how what he wanted, what he wanted of each step. Of course… maybe one day that none of us that knew John is there, but… my work now is to pass [on to] the other generations, through different companies, everything that Cranko was. Whenever I go to another company I sit with the company and they always want to know how it was to work with Fred [Frederick Ashton], how it was to work with MacMillan. What’s the difference between the two of them; how it was to have both of them, at the same time, in one theatre.

Patricia Linton: Can you talk about that, the differences?

Marcia Haydée: Yes, it’s totally different. Cranko: at least he knew the music very well and he knew what he wanted, but he didn’t have the choreography in his head. That was something that he used to come, would close the doors of the studio, the music started, and then he said, “Marcia, Ray, Vicky, if you run, now lift her this way”, and that’s how it worked.

Instead, with Kenneth, when he came, he already had, and he said the movements that he wanted; it was a different approach. Kenneth was very particular with how he wanted this step or the other step, or how to do it. And sometimes he wanted something that was absolutely impossible. I remember one moment in [Las] Hermanas that he wanted me to bend my knees this way, and I said, “Kenneth, it doesn’t… look.” He said, “Yes, Marcia, you must go”, and, really, I was grabbing Ray [Barra], and he wanted me to perform with the leg this way and I want to go that way, and then he said, “Yes, it’s true. Because I really thought it could go this way”. So, Kenneth was very particular with his movements.

Patricia Linton: And would you then work out a compromise that fulfilled this vision that he had?

Marcia Haydée: No, I never compromised. Whatever he wanted, I used to…

Patricia Linton: So, you would always find a way, you had this picture?

Marcia Haydée: And this one [time], he said, “Marcia; it’s impossible unless [you] will do an operation so that your knee can bend this way.” But I always give, 100 percent, what the choreographer wanted.

Patricia Linton: Can I ask you some questions about Onegin?

Marcia Haydée: Yes, please.

Patricia Linton: In a very short time – two hours of the ballet – you go from a very young girl to a mature [woman]…

Marcia Haydée: But you know the real story of Onegin, do you? That he [Cranko] wanted [to make it] for [Rudolf] Nureyev. The original, he wanted Nureyev as Onegin, [Margot] Fonteyn as Tatiana, Antoinette Sibley as Olga and Anthony Dowell [as Lensky]. And he went to London – he wanted to do it for The Royal Ballet – and when he went to London, the board of directors says no, we’re not going to do [it] because it’s a very… we have a very successful [production] with the opera, [Eugene] Onegin, and they didn’t think that a ballet would be so successful. So, Cranko came back [to Stuttgart] and he said, “OK kids, let’s do it here, they don’t want in London, so.” And the day that I told Nureyev that Cranko had thought for him, I thought he was ready to burn the whole of England.

Patricia Linton: He would have loved that role.

Marcia Haydée: Oh, [it] was for him. And, of course, the Onegin that Cranko did here is totally different than [the] Onegin he would have done there, because there Rudi was at the top of his career, so that was for Onegin; that was for Rudi. Margot was already going to… more to the end of her career, so the dancing would have been done with… the pas de deux would have been totally different. Instead, when he [Cranko] came here, the Onegin that was Ray Barra, he [Barra] had already a problem with his Achilles [tendon], so he couldn’t dance, he just did one solo. He had one solo, [and] the rest was all in the hands of Tatiana. Lensky was the boy that did all the variations, but not Onegin, but I’m glad that it came here. The life knows sometimes what it does, no?

Patricia Linton: So, now I’m going to talk about MacMillan and Song of the Earth. He said at one time that this was the ballet that he wanted to be remembered for…

Marcia Haydée: I think, yes, I can believe [that], because for me it’s a perfect ballet for MacMillan. It’s really amazing, and the way he choreographed, how fast he choreographed that ballet! At the end of the ballet, that for me is a jewel, in the sixth movement you start to do, just at the end, that bourrée, you know, before you die. ‘Til the general rehearsal, he didn’t have an end; he didn’t know what to do, and suddenly he got me up and [in] the ballet room [studio] said, “Marcia… do bourrée, do bourrée there, do bourrée there, then collapse, and use your arms,” and [he] threw me on stage, and I did. And that’s how it was created – the last, the end of Song of the Earth.

Today, Mahler – it’s normal that you dance [to] Mahler. But at that time, it was quite a scandal that MacMillan wanted to do a ballet with Mahler. And, again, he wanted to do [it] in The Royal Ballet, and they said no. So, he phoned Cranko and Cranko said, “OK Ken, come, let’s do it here.” And at that time, [it] was the same time Cranko [was] working on Opus I. Kenneth MacMillan was working [on] Song of the Earth. That was two great choreographers together in one theatre; that’s something that really nobody can have like we had; it was a very special time.

Patricia Linton: How did you feel when you came to London and you did it? The first performances there, [with] Donald MacLeary, Anthony Dowell. How did that feel? You had to teach them very quickly?

Marcia Haydée: It feels different because the scenery was different, the colours were different.

Patricia Linton: Did that make a difference, the colours?

Marcia Haydée: It does make a difference because there [in London], [designer Nicholas] Georgiadis did it everything was more in black and grey, and here [in Stuttgart] each movement had the autumn colours, you know, so it was something different. And, of course, Donald was a fantastic partner. It was created for me with Ray and with Egon [Madsen], and Anthony Dowell was not Egon and Egon was not Anthony Dowell; Egon was more dramatic and Anthony Dowell, dance wise, was more perfect. So, yes, it was a different situation.

Patricia Linton: Did you worry about it?

Marcia Haydée: No, I loved it; I loved doing it. I was in the School and then suddenly [I] come back as a guest to The Royal Ballet, to do Song of the Earth, with all those fantastic dancers that they had. I loved Song of the Earth.

Patricia Linton: Have you ever found anybody who’s danced it in the way that has made you happy, internally or externally?

Marcia Haydée: No. They are fantastic dancers that have danced Song of the Earth, they were amazing, but there was a question of speed that we had in that time; we all danced much faster than [the] dancers [of] today. Maybe because today, with those dancers I use, when I look for those films of Beriosova or Moira Shearer, they had the speed on dancing that was amazing, and that’s what Cranko wanted, and we were like that. We danced Romeo or Onegin, Swan Lake; everything we danced much faster than what they do today, because that was the time, dances were like Balanchine: move, move, move; don’t be comfortable.

Patricia Linton: I think, also, Reid Anderson [another Stuttgart Ballet dancer and director] has said somewhere that the final pas de deux is danced differently now, that they dance it more prettily as a love duet rather than [it] standing for the monumental feelings in the music, is that…

Marcia Haydée: Absolutely right.

Patricia Linton: Why do you think that’s happened?

Marcia Haydée: Because there’s certain things that you can’t copy – you can’t. It was the situation with Kenneth, with me, with Ray, and what he wanted, you know? That tragedy of this woman that was alone in the second movement and in the last movement she meets the man, and when, suddenly, there is this love between them Death comes, it takes you. It’s a very strong situation, and I was never scared of anything; I used to throw myself. The dancers [of] today, they control, but they don’t throw themselves. The risks that there was in the pas de deux, there were many difficult things in Song of the Earth in the pas de deux. The dancers today, they don’t do it. It’s a question of not being afraid, it’s a question of not really trying to make pretty lines. You just become the music, and that music is very strong, and you really have to become that. And it is true that I find that they don’t achieve what we did.

One can explain but it has to do with the situation that was created here. That was the magic of that moment. [It] had nothing to do with good dancers, bad dancers. No. There was a magic, magical moment here when they created Song of the Earth. It was a very, very special situation.

The transcript of this podcast may have been lightly edited for ease of reading.