Anastasia was originally choreographed in 1967 by Kenneth MacMillan as a one-act ballet for Lynn Seymour and the Deutsche Oper Ballet Berlin, with music by Bohuslav Martinů and designs by Barry Kay. It highlighted the plight of Anna Anderson, who claimed plausibly (but falsely, it later turned out) to be the Grand Duchess Anastasia, the Russian Tsar’s youngest daughter, who was rumoured to have survived the execution of the rest of her family in 1918. The ballet was innovative choreographically and theatrically, including harrowing and haunting film footage of the Imperial family as well as the 1917 Russian Revolution, and focused on Anderson’s incarceration in a mental hospital, and her flashbacks to her supposed imperial past.

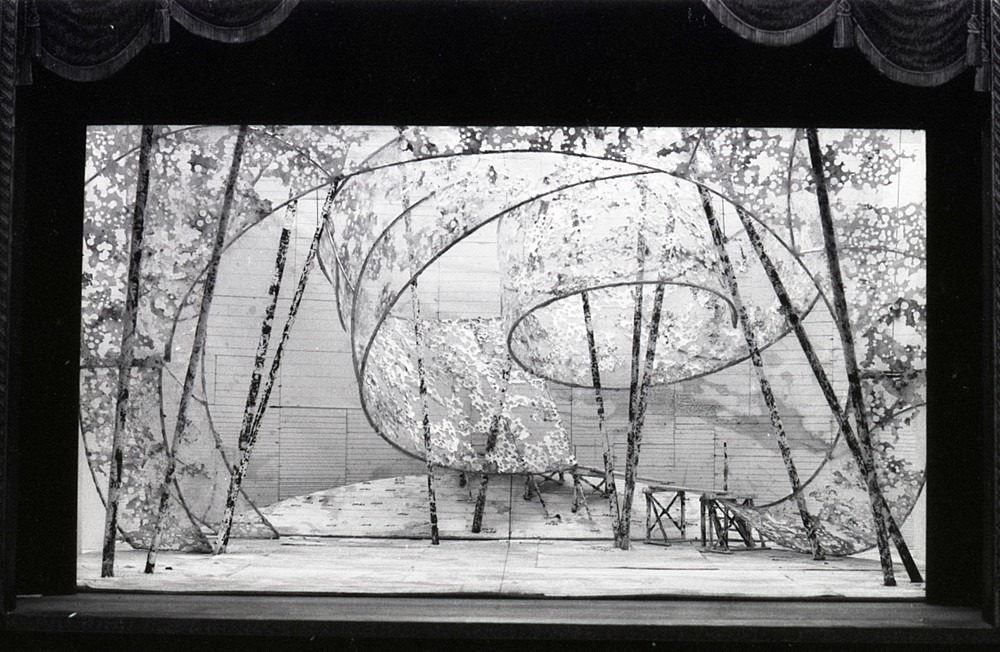

When MacMillan returned to London in 1970 as director of The Royal Ballet, his first new work for the company was to develop the Berlin one-act work into a full-length ballet, with Kay designing again. It was a huge and courageous undertaking. Leaving the original work to end the ballet as its third act, MacMillan added two earlier acts, using Tchaikovsky’s First Symphony for Act I and his Third Symphony for Act II. Though generally regarded by critics and musicians alike as a step too far, Anastasia was utterly compelling. Act I was an extraordinary attempt to evoke the intimate family life of the Romanovs on holiday, which is cut short by the declaration of the First World War. Act II, using the metaphor of Anastasia’s coming-out ball in 1917, ends with the sacking of the Winter Palace by the Revolutionaries, symbolising all the horrors and terrors shortly to be unleashed. Grigori Rasputin looms, a constant figure of doom, and the lovely Romanov daughters hover unknowingly on the threshold of adulthood and tragedy, their tragedy. From her carefree entrance on roller skates in Act I to her anguished cries in a mental hospital in Act III, Seymour’s performance as Anastasia/Anna Anderson made the audience question the very nature of personal identity. The one-act version of the ballet has been revived in New York, Stuttgart and London, but this profound and moving ballet is always going to be difficult to resuscitate, given that we now know for certain that Anna Anderson was a fantasist.