Wendy Toye

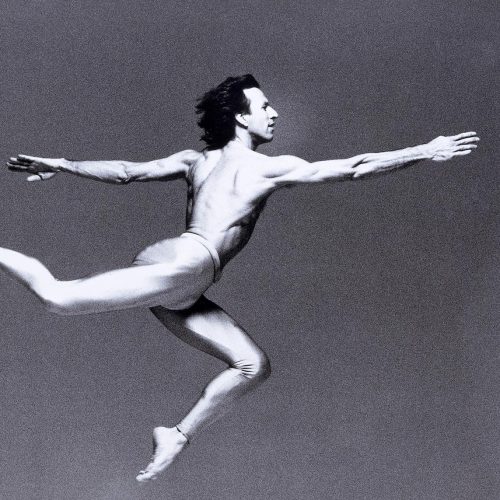

The dancer and choreographer Adam Cooper introduces this wonderful interview with the dancer, choreographer, stage and film director Wendy Toye who begins by recalling chatting to Serge Diaghilev at the age of nine, giving her opinion of L’Après-Midi d’un faune. She goes on to tell Patricia Linton of her love for dancing of all sorts. From the age of five she performed in Hiawatha at the Royal Albert Hall. At 14 she became a member of the Vic-Wells Ballet, while dancing commercially as well. She speaks of touring in Denmark, with Adeleine Genée leading the company, and being singled out by the Prince of Wales. Her career, in the 1930s and subsequently, involved films, shows, cabaret and television, as well as ballet, opera and choreography. At the age of 90 she reflects on how she worked in so many fields, not, as she says, peaking in any of them, but having enjoyed all of it and all of them.

First published: March 23, 2025

Biography

Wendy Toye was born in Clapton in 1917, and very early showed considerable balletic and theatrical talent. As a child she was often appearing on the stage, as well as taking serious ballet lessons from Tamara Karsavina, among others. She won the European Charleston Championship at the age of nine. In 1931, she joined the Vic-Wells Ballet Company, though continuing to work in cabaret. She then worked for the Markova-Dolin Company from 1934-5, and choreographed the ballet Aucassin and Nicolette for them. In 1937, partly as a result of an appendix operation, she ceased to dance in ballet, and embarked on her long, distinguished and industrious career in the commercial theatre, films and television, as actress, dancer, choreographer and director (which, in her later years, included directing a number of operas, particularly for Sadler’s Wells/English National Opera). Wendy Toye was appointed CBE in 1992 for services to the arts. She died in Hillingdon in 2010.

Transcript

In conversation with Patricia Linton

Wendy Toye: Well, I was born in 1917 in a place called Clapton. And my mother, I think, always wanted to be a dancer, which is, I think, why I found myself being involved in such interesting things, like all the rehearsals of the Diaghilev Ballet Company [Les Ballets Russes de Serge Diaghilev] when they came to London. Somehow or another, she managed to wangle us both in, really and truly, because she wanted to be there much more than that she wanted me to be there. But she used to say that I was training to be a dancer. I was very young. Mr. Diaghilev came to know me because I was there such a lot and once I was watching L’Après Midi – The Afternoon of the Faun – and Diaghilev came up to me and asked what I thought of it. And I was only nine or something, I suppose. And I said, ‘Well, I loved it. But,’ I said, ‘it seems strange to me that the music was so circular and round and soft and all the actions were so angular like this.’ And he patted me on the head. And said ‘Ah, Wendy, that is genius!’

Patricia Linton: What you or [Vaslav] Nijinsky?

Wendy Toye: Nijinsky!

Patricia Linton: Who did you actually start training with?

Wendy Toye: I started with a wonderful woman called Susie Boyle in Islington, and she had a business partner and he was an American called Fred Dixon. And he arranged two or three little dances for me, which were very special and very clever. And when I was very young, about 7 or 8, I was always asked to dance for charity because I was very small, as well as being very young. I was very tiny. I looked more like 5 than 7. I was quite famous in those days.

Patricia Linton: So Susie Boyle, she taught you classical ballet?

Wendy Toye: Oh, no. In those days it was called ‘fancy dancing’. I was only 3, but I did all sorts of dancing and I started tap very early and I won the Charleston championship when I was only 9 years old. I was the only child entered, and it was the European Charleston championship that I won, which was amazing, really, because I was the only child entered.

Patricia Linton: And you must have started it a couple of years before that.

Wendy Toye: Oh, yes. I started dancing, got dancing classes quite seriously from the age of 5, about twice a week.

Patricia Linton: I think I read somewhere that you are a stooge for a comedian. Is that the right word?

Wendy Toye: A stooge? Well, I was. Wonderful man. He wasn’t really a comedian. He was a man called Hayden Coffin, who was a wonderful singer. And he did a series of sea shanties. And I used to come on and do the sailor’s hornpipe when he was singing these sea shanties in my little sailor’s suit.

Patricia Linton: And you did the sailor’s hornpipe quite a lot, didn’t you?

Wendy Toye: Yes, I did. All over the place – for charity, everywhere.

Patricia Linton: You did it in the Nottingham Theatre Royal. It was a charity matinee and I think the Duke and Duchess of Newcastle had arranged it. But I think you danced there with Karsavina and Keith Lester?

Wendy Toye: Yes, when I was a pupil of Karsavina’s. She was one of my teachers.

Patricia Linton: Where would that have taken place?

Wendy Toye: In London. I do remember going to tea in her house for the first time. I went many times, but the very first time I was very impressed because I was only very small. I was young, but I was very small for my age anyway. And the door handles were glass and I’d never seen glass door handles before, and they were all high up on the doors and I couldn’t reach them. Oh, I remember that so well.

Patricia Linton: So you remember her more for her person rather than actually teaching you?

Wendy Toye: No, I remember her teaching me very well. I usually had private lessons because being a child it was difficult for me to go to class because they were all in the mornings. In the end I had a governess so that I could have my lessons in the afternoons and go to dancing classes in the mornings.

Patricia Linton: What most valuable about your work with Karsavina?

Wendy Toye: I think the artistry. I think she never taught one anything without giving it a meaning or giving it a little story. After one had done the basic exercises at the barre and then the basic exercises in the centre. Everything you did had a little story, had a little mime to it, so you learnt to act with it. I think that’s what I remember.

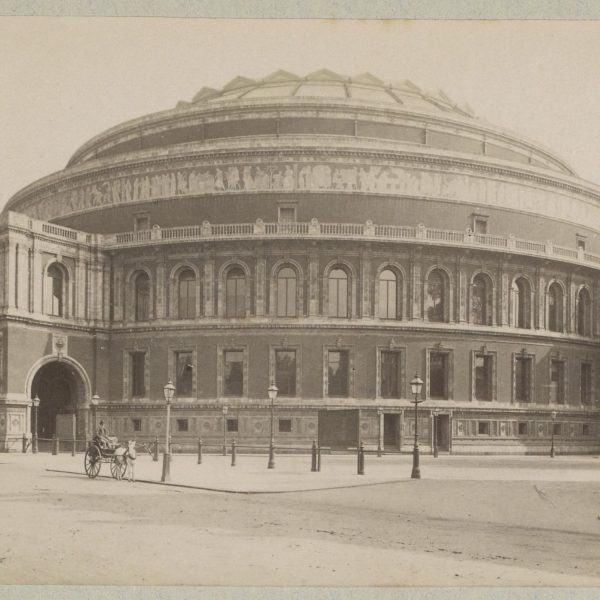

Patricia Linton: Phyllis Bedells talks about you quite a lot in the book that she wrote. I think you danced when you again were quite young as an attendant in a big ballet at the Albert Hall.

Wendy Toye: In Hiawatha, the Albert Hall, or there were hundreds of people in it, literally hundreds, but they were all amateurs, you see, and they were all free. And nobody got paid for a fortnight for a whole fortnight every year.

Patricia Linton: So it came on every year.

Wendy Toye: Yes, I think I did it for about 10 years running. I was in it first when I was 5. Special little part was made for me in it because I was, I mean, there’s no harm in saying, so I was a really very good dancer as a child. Exceptional. So they arranged a special little part for me, which was lovely.

Patricia Linton: When you were 9, I think you choreographed a ballet?

Wendy Toye: At The Palladium.

Patricia Linton: Music by, yes, Scarlatti.

Wendy Toye: Well, a lot of it was Scarlatti. There was some other pieces, too, of the same period.

Patricia Linton: The Japanese Legend of the Rainbow.

Wendy Toye: I made it up. Yes, I called it The Japanese Legend of the Rainbow, which was when the flowers die, their colours go to make the rainbow, which I thought was rather crafty, rather clever at that age. I was what? I was 9. Yes. Not a bad idea what I did. I don’t know.

Patricia Linton: You were in the production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream at the Old Vic, I think, in 1929.

Wendy Toye: Yes, I was one of the four fairies. I set John Gielgud on fire.

Patricia Linton: Oh, you didn’t?

Wendy Toye: Yes. Well, I had a torch and we used to have to go to the stage management and have a wad of cotton wool put in a little drop of petrol, and then they’d light it. And on we went and I bowed with too much energy and my wad came out onto his cape and set him on fire and he rushed around the stage twice on fire and then flew off to be put out.

Patricia Linton: Were you mortified?

Wendy Toye: Oh, terrible. And I was taken up in front of Lilian Baylis. ‘Very, very careless, Wendy. Very, very careless. We’ll have to dock your salary.’ They’d dock your salary for anything because it was so poor and it was only 7 and 6 a performance.

Patricia Linton: Was it at that time that you became involved in The Vic-Wells ballet and Ninette de Valois?

Wendy Toye: Yes, it was about that time because I was very young when I was first in the company as a guest artist.

Patricia Linton: Well, so by 1931, you were a member of the Vic-Wells Ballet. At that point, did you feel a sort of narrowing of your focus. Because you’ve done so much at that point?

Wendy Toye: No, not at all. Because that was my mother. She always insisted on me doing a lot of other things as well, a lot of commercial things and a lot of tap dancing and character dancing, as well as classical and ballet. And so I was always involved in so many other things outside the ballet serious.

Patricia Linton: Do you remember going to Denmark?

Wendy Toye: Yes, very well.

Patricia Linton: I think that was in about 1932.

Wendy Toye: Adeline Genée led the company, who was Danish. But the thing I remember most was that I was doing a Mexican solo. That was my solo.

Patricia Linton: Is this your Mexican hat dance?

Wendy Toye: Yes. And I was the first person ever to do it in this country. And then I taught it to a lot of other people. And the Prince of Wales, the then Prince of Wales, he was at one of the performances, and he sent a note round to Ninette de Valois to say that if they would ask Wendy Toye to dance the English National Hornpipe, he’d come again. They had to send back to England for my sailor suit and everything. I did it. Yes.

Patricia Linton: So I think at that time when you were in Copenhagen, you did these ballets there. And I wondered if you remember anything about them. Homage aux Belles Viennoises. Do you remember that?

Wendy Toye: Yes, I was in that. I was in that as an understudy. And there was one night when there was Jackdaw and the Pigeons, the Viennese ballet. And a third one that I can’t remember what it was. A girl was off who was in all three ballets, and I had to learn all three parts in that day. So I learnt two of them in the morning and then I learnt the third one in the interval between two of the ballets. It was really a panic.

Patricia Linton: In 1932, you choreographed A Willow Grows Aslant a Brook.

Wendy Toye: Yes.

Patricia Linton: Was that for the Carmargo Society? I think it might have been at the Adelphi.

Wendy Toye: Yes. I can’t remember if I wasn’t very good, but I was lucky to get the opportunity to do it. I don’t know why I was given the chance to do it, I’m sure.

Patricia Linton: It’s quite interesting that all through this time, a bit later on with Marie Rambert as well, there were a lot of women. They didn’t discriminate against women. I mean, men and women were both choreographing.

Wendy Toye: Yes.

Patricia Linton: Sort of reading about that, that particular time. There seem to be so many ballets by Andrée Howard and Susan Salaman. Did you know them?

Wendy Toye: Yes. Andrée was ever so willowy. Everything was white. I went to her flat once and everything was painted white. She’d done it herself. All the furniture, chairs, everything. It was lovely. I was very impressed. I loved it. And she was very white and willowy in her personality somehow. And very clever. She did some lovely work.

Patricia Linton: I think you danced a bit later on when you were with the Rambert Company [Ballet Rambert, now Rambert] in the late 1930s. You danced in a few of her ballets. You did…

Wendy Toye: Yes, I’m sure.

Patricia Linton: …La Muse S’amuse

Wendy Toye: Oh, yes. I was the principal in La Muse S’amuse. Yes, that was lovely. It was a comic ballet. I was very good at comedy and I used to get all the funny bits to do. There was a can-can that we used to do and it was always one of the divertissements and it was a perfectly straight can-can, absolutely straightforward and very, very boring. Choreographed by Molly Lake. And it couldn’t have been duller. And we did the first performance of it, and I suddenly found myself acting as though I couldn’t quite do anything properly, couldn’t do the splits, couldn’t do the high kicks, and it started getting laughs. And it was hilarious. And, she couldn’t be cross with me because it was such a success. It was a huge success. And then Diana Gould was in it as well. And the next performance, Diana Gould joined in with me and started doing the same sort of thing, which was a bit naughty of her. Anyway, we were both tearing about not doing it very well and it rather spoilt it.

Patricia Linton: When you were with Diana Gould, what company was that? Was that the Markova-Dolin?

Wendy Toye: Markova-Dolin. And the Rambert, of course, I was in with her.

Patricia Linton: You did a ballet when you were with the Markova-Dolin company? Aucassin ….

Wendy Toye: Aucassin And Nicolette. Yes.

Patricia Linton: The music was by Joseph Holbrooke. Yes. And it was designed by…

Wendy Toye: Motley [Theatre Design Group]. Well, there were three girls, very famous Motley were and they used to do all John Gielgud’s plays and they were brilliant. And Sophie Harris was one of them. Elizabeth Montgomery was another one. And Sophie Harris’s sister was the third. Percy. Percy [Margaret] Harris. But it was a girl. And they were the Motley and everything until the Motleys came on the scene was sort of a box set with stiff wings. With a cloth at the back, and they started all this wonderful, airy-fairy material, which was a very, very different look and beautiful, especially for dancing. It was wonderful.

Patricia Linton: When you were with the Markova-Dolin, which is a sort of the mid 1930s, I think Bronislava Nijinska came and did a couple of ballets.

Wendy Toye: Yes, she did. But unfortunately I was rushed from on tour with a very, very broken bust up appendix and I was very ill. I was rushed into hospital and nowadays probably you’d have been in for two days and out and back again. But in those days it was a five week job, and they didn’t take me back.

Patricia Linton: And that must have been very disappointing for you.

Wendy Toye: Oh, it was heartbreaking.

Patricia Linton: What did you do? Picked yourself up?

Wendy Toye: Oh, I went straight into some commercial job. Yes.

Patricia Linton: And it was after that that you joined the Rambert. In about 1937, I think you joined the Rambert. But you’d been in Invitation to the Waltz.

Wendy Toye: The film.

Patricia Linton: Must have been around that time.

Wendy Toye: Yes. And that was interesting because [Anton] Dolin was hired to choreograph the big ballet in it, and Lillian Harvey was the star and he came to the first rehearsal and Lillian Harvey was going to be in it. And Pat [Dolin] absolutely fell hook, line and sinker in love with her. Dolin did. And she was off to Paris for some reason or another, I think, to have fittings for her costumes. And he said, well, get on with it, Wendy and off he went to Paris with her and left me to choreograph the whole thing.

Patricia Linton: And you were only about 17, 1935.

Wendy Toye: Yes, about 17.

Patricia Linton: So all through the 1930s, you’ve been in films and shows, television, cabarets, cabaret. You’ve been choreographing. You’ve been choreographed on.

Wendy Toye: Yes, I’ve been very lucky. I think one or two people feel that if I had stuck to one thing, it would have been better for me and I’d have been more important in that one thing. But I’ve enjoyed doing so many different things. It means that I haven’t reached the peak in any of them, but I don’t think that matters. It didn’t matter to me. I just enjoyed doing it all very much

The transcript of this podcast may have been lightly edited for ease of reading.