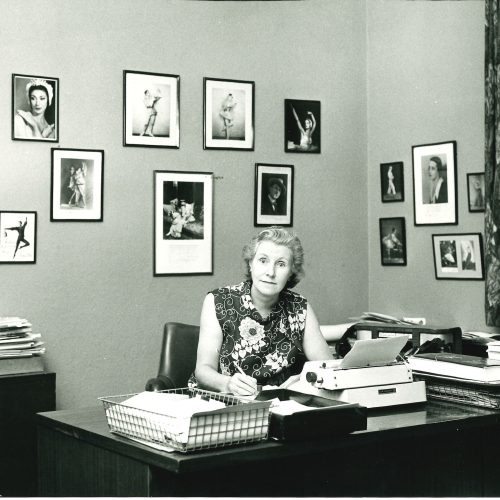

Mary Clarke

It is thanks to her godson, Jerome Monahan, that we have this evocative and informative clip of Mary Clarke. Writer extraordinaire on all aspects of ballet, she hated the sound of her own voice and even more the look of her transcript. In these few minutes, however, she manages to convey the feeling of several eras, and of many people and happenings. She also explains, in her low-key erudite way, how the word ‘balletomane’ entered the English language. Mary is interviewed by her friend, the former Royal Ballet soloist Meryl Chappell, and the interview is introduced by Jonathan Gray, former editor of Dancing Times, who worked closely with Mary during her later years.

First published: October 20, 2025

Biography

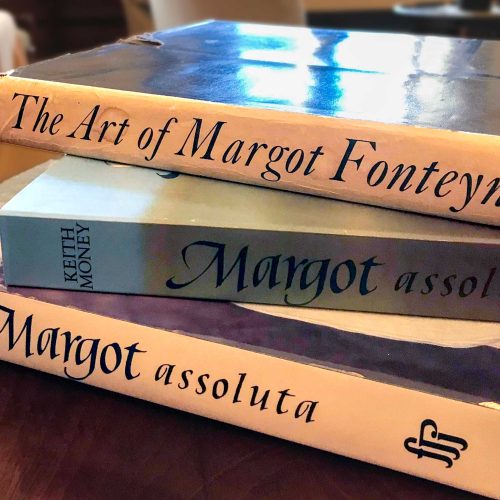

Mary Clarke was the dance historian and writer par excellence. Her two books on the birth of British ballet in the 20th Century – The Sadler’s Wells Ballet: A History and Appreciation (London, 1955) and Dancers of Mercury: The Story of Ballet Rambert (London, 1962) – remain the starting point for all future historians of ballet in the UK.

Mary Clarke was born in London in 1923. After her schooling at Mary Datchelor School, she worked as a typist at Reuter’s Press Agency. She was a youthful enthusiast for ballet and all things theatrical, and her career as a ballet critic and journalist began in 1943 with her first published article (prophetically for Dancing Times) and with her appointment in the same year as London correspondent for the American Dance Magazine. After the end of the war Clarke wrote for the London-based Ballet Today magazine. From the mid-1950s until 1970 she was also the London correspondent for Dance News, another American publication, which was then run by the distinguished critic and writer Anatole Chujoy. In 1954 Clarke became the assistant editor of Dancing Times, first under Philip Richardson and then for Arthur Franks. On Franks’ sudden death in 1963, Clarke became editor of Dancing Times, a post she held until her retirement in 2010. For over half a century she chronicled the changing trends in ballet and dance worldwide and their effects with impeccable judgement and an encyclopaedic knowledge.

Clarke was dance critic for The Guardian newspaper from 1977 to 1994 and associate editor (with Arnold L Haskell) for many years of the Ballet Annual. She co-authored a range of books with the ballet critic and writer, Clement Crisp, notably Ballet: An Illustrated History (London, 1973) and The Encyclopaedia of Dance and Ballet (London, 1977) with David Vaughan. Her quiet demeanour and straightforward style belied deep thought and high ambition for the art. Her contributions to A Dictionary of Modern Ballet (London, 1959) are awe-inspiring in their clarity and humanity, qualities rare in a critic. She was awarded the Queen Elizabeth II Coronation Award of the Royal Academy of Dance in 1990, Poland’s Nijinsky Medal in 1996, and she was made a Knight of the Order of Dannebrog in 1992.

Transcript

in conversation with Meryl Chappell

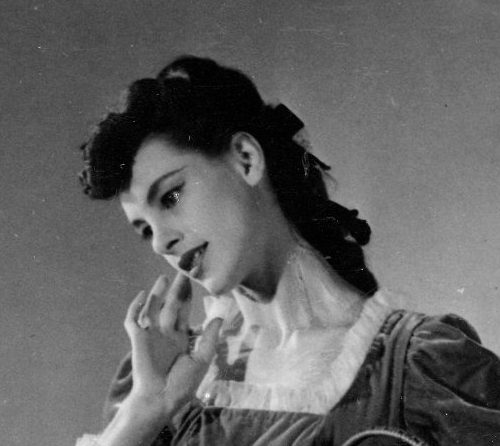

Mary Clarke: The first performance I ever saw was at Streatham Hill Theatre. The company was the Markova-Dolin company. Alicia Markova was the Sugar Plum Fairy and I always told Alicia when I got to know her many, many years later, that it was all her fault! I must also give credit to the fact that my first performance at Sadler’s Wells was Swan Lake, 70 years ago. It was Margot Fonteyn and Robert Helpmann. So, they were the introduction.

Meryl Chappell: Mary, you started writing about a dance…

Mary Clarke: I’ll tell you exactly how I started.

Meryl Chappell: Yes.

Mary Clarke: A marvellous teacher called Olive Ripman, who used to do articles for Dancing Times, used to run little competitions. One of them was ‘what you would expect of a ballet critic?’ or something like that. So, I entered the competition, said exactly what I expected, and I won the first prize, which was £1. Richness!

Meryl Chappell: Yes.

Mary Clarke: Then, I think really, why I started trying my hand at it, I was working at Reuters at the time – this was during the war, I was at Reuters. Again, through Dancing Times I found a pen friend in Chicago. A group of Balletomanes from Chicago wrote to the magazine and said, ‘Could they establish penfriends to keep in touch across the Atlantic during the war years?’

Meryl Chappell: Gosh.

Mary Clarke: I started writing to a young man in Chicago called Herbert J Curtis, and that correspondence continued until last year when he died.

Meryl Chappell: No? Mary, really?

Mary Clarke: He would write long accounts of what was going on [in Chicago]. Then I used to write long, long letters back about what was happening here. A friend of mine at Reuters came past one day – it showed how little work I was doing; I was busy typing my letter to Chicago! She said, ‘What’s this? Can I have a look at it?’ ‘Oh, yes, yes.’ ‘Oh,’ she said, ‘This is interesting. Why don’t you send an article to somewhere.’ So, on the strength of that I sent an article to Mr Richardson, who was then editor of Dancing Times, and it was a very cross article. It was the time when [Robert] Helpmann was doing Comus. I called it the ‘Literary Ballet’ and wrote an article of strong disapproval of the way ballet was going, you know, it wasn’t ballet’s job to do that kind of thing.

Meryl Chappell: Didn’t need to be a play?

Mary Clarke: Anyway, Mr Richardson published it, and I think he sent me £1 for that! That seemed to be the going rate in those days. [Laughs] Then on the strength of that, you know, then I decided, yes, perhaps I could do something like this. I wrote simply out of the blue to the American Dance Magazine offering my services as a London correspondent, and they said, ‘Yes.’ And from there I went to Dance News, which Anatole Chujoy ran in those days. A very, very good slight newspaper. They used to ask for – Mr Chujoy did – he always wanted, if it was a big first night here, he wanted to know who was in the audience and that kind of thing.

Meryl Chappell: Oh really?

Mary Clarke: Yes. [Laughs] It seems funny now.

Meryl Chappell: And were there many critics for you to read at that time in ballet?

Mary Clarke: Absolutely. I have to owe an enormous debt to the woman who wrote the first book about the Vic-Wells Ballet, P W Manchester.

Meryl Chappell: Ah, yes.

Mary Clarke: Her name was Phyllis Winifred which, not surprisingly, she disliked intensely. She was always, always known by the nickname ‘Bill’.

She was a very, very, very, perceptive writer, a good critic. She started going in [the] late Diaghilev years. She saw the end of the Diaghilev years. A great friend of hers was Philip Dyer, late of the Theatre Museum, and it was through knowing those two that I got to know – although I didn’t see it – something of the end of the Diaghilev and the Ballets Russes, which they knew very well indeed.

Meryl Chappell: Yes. Yes.

Mary Clarke: Bill, of course, published me when she started her own magazine called Ballet Today. That’s when I did my first magazine reviewing in this country. And, about the same time, again, after the war, Arnold Haskell asked me to work on Ballet Annual. Haskell also was a great influence, a great help, as was Mr Richardson of the Dancing Times. On the whole, at that period, nearly all the criticism in newspapers was done by the music critic.

Meryl Chappell: Was it?

Mary Clarke: It depended entirely on whether he was knowledgeable or not, as to what the standards were. Some people were very good indeed. Somebody like Frank Howes, the music critic of The Times, was knowledgeable on dance, and was a great friend of Joan Lawson, who taught him more. Arnold Haskell, of course, had a very, very wide knowledge of the arts. From the historical point of view, of course, one learnt most from Cyril Beaumont, his books, you know, gave us a real taste of ballet history, as did Arnold Haskell’s. Arnold was far and away the best-selling ballet writer of all time. His little Pelican [book] Ballet sold over a million copies. Of course, his popular book, Balletomania: the story of an obsession, published in the mid 1930s, again is a bestseller.

Meryl Chappell: He coined the name, didn’t he, ‘Balletomane’?

Mary Clarke: Yes. He introduced the word ‘Balletomane’ into the English language and into the Oxford Dictionary.

Meryl Chappell: Did you start writing, I mean you’ve written so many books, so many extraordinary books on ballet from every aspect, really. A lot of them with Clement Crisp.

Mary Clarke: Oh no. I started on my own.

Meryl Chappell: Yes.

Mary Clarke: The first book I ever did was The History of the Sadler’s Wells Ballet. I think that was published in 1954 or 1955.

Meryl Chappell: Yes.

Mary Clarke: Of course, it was a marvellous time to do it, because they [the company] had just become ‘Royal’ [The Royal Ballet]. I did it entirely myself. It was not commissioned by the company. After that one I had a phone call from Madam Rambert!

Meryl Chappell: Of course. [Laughs]

Mary Clarke: ‘You have done,’ she always exaggerated, ‘You have done this marvellous good book, but what about Ballet Rambert?’ I said, ‘Well, yes, I’d like to do it, but can I please do your life story leading up to it?’ So, she agreed. It worked marvellously, because I used to go and have dinner with her at her house at Camden Hill. She had a wonderful gift of talking in chapters. Rambert couldn’t cook at all, but she had a marvellous housekeeper called Helen, who would leave a casserole or something. So, we would eat, and we’d sit round the fire, and she’d start talking. When it came to a certain point, she should say, ‘Mary, I’m tired. We must stop.’ So, we stopped. When I got home and wrote up the notes, it was a logical break. She simply talked in chapters.

Meryl Chappell: So that was your second book. Then you went on – you’ve written how many, Mary, have you lost count?

Mary Clarke: I was working on Ballet Annual with Haskell for quite a long time.

Meryl Chappell: Yes. Yes.

Mary Clarke: I started doing the books with Clement Crisp when Blacks wanted a book, an illustrated book for intelligent teenagers. I said, ‘Well, I’d quite like to do it, but I can’t do the whole of it, I can’t do all the different periods. We did five chapters each. Fortunately, nobody ever figured out who did which. There was one famous occasion where, as we finished the last page of one book, we put the – in those days it was paper into typewriter – and started the next one.

Meryl Chappell: Gosh.

Mary Clarke: It was just extraordinary. I mean, we got so many commissions.

Meryl Chappell: Yes. And we must talk about the Dancing Times because that’s been really such an important part of your life.

Mary Clarke: I’ll tell you exactly how I got to the Dancing Times, because another marvellous job I had was [when] Richard Buckle asked me to help him edit the revised catalogue for the London [Diaghilev] Exhibition. I saw that great Diaghilev Exhibition up in Edinburgh. Then, when The Observer brought it to London to Forbes House, Dicky wanted the catalogue updated. It was when I showed Arthur Franks [around], who’d been the assistant editor, by then he’d taken over from Richardson as editor.

Meryl Chappell: Is this the 1960s?

Mary Clarke: 1954.

Meryl Chappell: 1954, is it?

Mary Clarke: The exhibition is. I helped at the press conference. I was taking Arthur Franks around… and that was when he asked me if I’d join Dancing Times, as assistant editor. So, it was immediately from the Diaghilev Exhibition that I joined the company. It was then [in] a very squalid little office in Henrietta Street, Covent Garden. The only polite way to describe them was to say Dickensian. Henrietta Street – 12 Henrietta Street – had a throughway to Maiden Lane at the back, so it was used as a cut through. Covent Garden Market was still there, of course.

Meryl Chappell: Yes, of course.

Mary Clarke: Richard Buckle had a flat at the top of our bank, which made me a little nervous at times. It was all there. The market was one thing; it was great fun. Late at night, you know, upstairs in Buckle’s flat after a party or dinner or something, and you looked down – he was right at the top – you could see the whole market coming to life in the early hours, which was marvellous. The actual offices [of Dancing Times] were very squalid. Mr Richardson used to come in about three days a week briefly. He would come in at about 11 in the morning – he had a car down from Belsize Park where he lived. Then he would toddle off to his favourite restaurant, Moulin d’Or in Romilly Street next to Kettner’s, where he entertained all those ballerinas he knew in those days, whom he persuaded to write for the magazine.

I think the strength of the magazine has always been the spread of coverage. Certain amounts of the magazine is definitely for the professionals, but also for the interested amateur. And a phrase that people use a tremendous lot, and it always pleases me, when they say that it keeps them in touch.

Meryl Chappell: Yes. Yes. Do you think the clientele has changed at all?

Mary Clarke: It changes the way the dance world is changed – has changed enormously over that period.

Meryl Chappell: Yes. Yes. Well, it has. I mean The Royal Ballet now, I mean, you, over these years you’ve seen it evolve and change under different directors and choreography, etc. It’s different, isn’t it?

Mary Clarke: It’s different, but on balance, I think the company is in very, very good shape at the moment, though I haven’t been for a year.

Meryl Chappell: No. Which is extraordinary, having been to every performance. I mean a critic’s life is not easy actually, is it?

Mary Clarke: Oh, not having to go to an opener is bliss. I moan to everybody, most of my Christmas cards this year, you know, I say, I haven’t been to a performance, I’ve been watching Swan Lake for 70 years and that is enough!

Meryl Chappell: That’s enough.

Mary Clarke: I’ve had Swan Lake, thank you very much!

The transcript of this podcast may have been lightly edited for ease of reading.