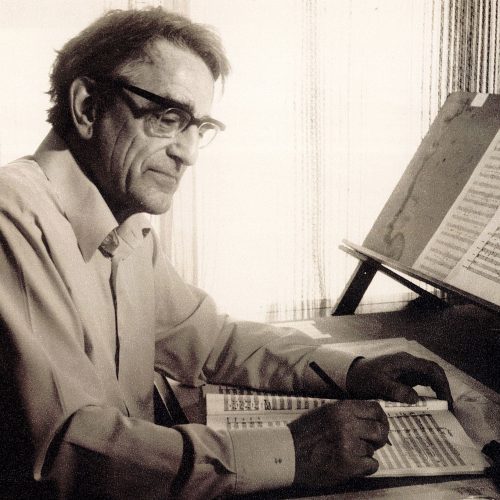

Ernest Tomlinson

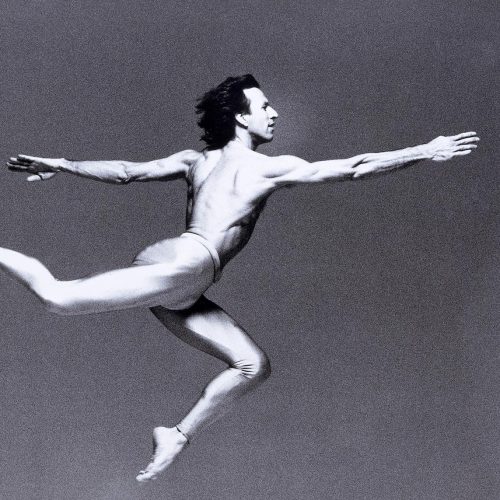

In this no-nonsense, down-to-earth account of writing music for Northern Ballet Theatre’s production of Aladdin, choreographed by Laverne Meyer in 1974, composer Ernest Tomlinson talks to Patricia Linton, founder and director of Voices of British Ballet. The interview is introduced by Stephen Johnson.

First published: December 23, 2025

Biography

Ernest Tomlinson was a British composer, well known for his contributions to light music and for founding The Library of Light Orchestral Music (which prevented the loss of 50,000 works released from the BBC’s archive and other collections). He wrote the music for the ballet Aladdin for Northern Ballet Theatre in 1974.

Tomlinson was born in 1924, in Rawtenstall, Lancashire. His parents were musical, and he sang as a chorister at Manchester Cathedral. After a grammar school education, he studied at Manchester University and the Royal Manchester School of Music, with a break for war service in the RAF. He moved to London after graduation in 1947, working first for music publishers. In 1955, after some of his compositions had been performed by the BBC, he formed his own orchestra – the Ernest Tomlinson Light Orchestra – and set out on a highly successful freelance career as a prolific composer, conductor and director of choirs and orchestras. He was particularly concerned to counter the notion of a strict division between art music and popular music. His own Sinfonia 62 was written for jazz band and symphony orchestra, while his Symphony 65 was performed at festivals in London and Munich and in the Soviet Union in 1966, where it was the first symphonic jazz to be heard there. In 1975, Tomlinson won his second Ivor Novello Award for his ballet, Aladdin. Among many other professional appointments, he was the chairman of the Light Music Society from 1966 until 2009. Ernest Tomlinson was appointed an MBE for his services to music in 2012.

Transcript

in conversation with Patricia Linton

Ernest Tomlinson: My father was a choirmaster, church choirmaster in St John’s, Crawshawbooth. He’d been a very good singer in his youth. He founded the Rossendale Male Voice Choir the same year he founded me, which was 1924. [Laughter]. So, that’s been my life, but the, the real key point was that, at the age of nine, he was always keen for his children to join Manchester Cathedral Choir. And there were thousands of boys [who] used to go in for these auditions, and I was kept, and kept, and kept. And so, I got this position singing in Manchester Cathedral Choir. So, from the age of nine, I was getting ten services a week. Well, at that time, services were like, I mean, well they’re like concerts, really. About an hour long. So, there’d be ten services a week, including two on Saturday and two on Sunday. This was our life. Our holiday was Monday. And we lived in a very, sort of, working class area in, in Rawtenstall. You know, backyard and no… no garden or anything. But I’d play with the lads, and everything, but then on a Sunday, I had an Eton suit and had to walk down to Rawtenstall station because the trains were good at that time.

Patricia Linton: Did they ever say anything, the other lads? You, looking so smart on a Sunday.

Ernest Tomlinson: Well, I suppose we got laughs now and again but, I think basically, most of them were, sort of, proud of the fact that this… one of their lads was, you know, achieving fame in Manchester.

Patricia Linton: No early interest in dance, at all?

Ernest Tomlinson: My sister was always very – my older sister – when she was still alive, she, she, was always interested in ballet. We’re now talking about wartime because the ballet companies and the opera companies would come up to Burnley and places like that to get out of London. So, we got Margot Fonteyn and people like that coming.

Patricia Linton: So, you actually went to watch?

Ernest Tomlinson: I went to watch them, yes. But I must say, I, I preferred ballet to opera because, I mean, I like music. I mean, I could just listen to music, you don’t need the ballet, really, I just want the, the tunes. And the thing about ballet – what attracted me from a writing point of view – is that you can write definite pieces of music. You don’t have to do like you do when I did this with opera. You’ve got to fit it to the script. It’s a script. I mean, you might write the script yourself but, but the music’s got to go around the script. Whereas in ballet, particularly the way Laverne Meyer did it, he wanted set items, several set items, and then what I call “recitative” in between, you know, where there’s action going on. But then they’d stop, for a ballet piece. Well, that, for a composer, is far more rewarding than anything to do with opera because opera, you’re always tied to the words. But once you’re on a set dance, and you know the length that they want it, you can be a composer. Just, you, you try and find the, the style that they’re looking for, but it gives you ample scope, and it was ample, you know? So, I, I preferred writing for ballet than anything else, really.

Patricia Linton: Well now we’ve got onto Aladdin. Did you know Laverne Meyer before this?

Ernest Tomlinson: No, no.

Patricia Linton: So, you, you say that, actually, you, you were quite interested in ballet before this?

Ernest Tomlinson: Well, I, I was interested, be fair. I was interested in the fact that something demanded melody. Tunes, dancers, and I was, was composing from the age of nine, and it was always melody. I mean my heroes were Schubert and Mozart, who, who could rattle off all these melodies. And I could rattle off melodies, and I like to think that, that fluency was… was such a gift.

Patricia Linton: And is that, that what’s important, the melody, in making emotional contact with the audience?

Ernest Tomlinson: I don’t think about emotions. I don’t think about – if they think about emotions, I don’t. I just write music. I don’t want it described or anything. I can go and write tunes without any need for… that was the thing that most inspires is the fact that somebody might perform it.

Patricia Linton: In the case of Aladdin, um, did, were you presented with a scenario?

Ernest Tomlinson: Yes.

Patricia Linton: Did you see the dancers before you started writing? What were your impressions of the dancers?

Ernest Tomlinson: Well, dancers are dancers, who are jolly good. I mean, I don’t, I can’t tell the difference with one and another.

Patricia Linton: [Laughter] So, did you… were you involved in this scenario, at all, or were you just presented with it?

Ernest Tomlinson: No, I think – generally speaking – the scenario was, was given to me. And, err, but then we’d make suggestions, then he [Meyer] might ask for a bit more music there and, something like that.

Patricia Linton: How did you respond to the demands of the choreography? How did Laverne communicate with you?

Ernest Tomlinson: Well, I mean it was just simply the story. It’s a story, and it’s a scene, and, you know? He, he tells us what the dancers are representing at the time. And that was a natural, really, just simply to think what, what dancers would… I mean, you… at that point, they’re not telling a story, they’re enjoying themselves, as it were.

Patricia Linton: Did you have any idea of the steps, or the particular movements? Did they mean anything to you?

Ernest Tomlinson: No, no. No.

Patricia Linton: You just, either liked or didn’t like the way they went with your music?

Ernest Tomlinson: Well, that’s right, yes indeed, yes. I mean the… the more I thought that they, they melded with the music, the better I liked it. I mean, I think, um, that that’s what it’s about. I think it’s one of the most difficult things to, to really gel the two together, so that you say, “That, that has to be that dancing, and that has to be that music.” I think that that doesn’t occur all that often.

Patricia Linton: Did they ask you to make any changes?

Ernest Tomlinson: Not really, of the pieces, no. I think they… it really felt that it was up to him to make it work, you know? That… that was what his challenge was, to make that work.

Patricia Linton: Oh right. So, he was more driven by more and what you had done?

Ernest Tomlinson: I think so, yes. But, um, the, the thing was, the, the time it took me to do it. They, um, I didn’t really start until Easter that year, and it was on in September. And that is two hours, over two hours of music. And it was the longest slog I’ve ever had in my history. I mean, when I was a staff arranger, just doing arrangements, I could just churn the stuff out. I learned how to work against a clock and all that, but this was composition, and I wanted it to be good tunes. And, and, that they wanted rehearsal piano, which I had to write. So, it… it was a long slog. The morning would be to, I’d try to compose it and then write piano part and send that off. And then the next day, start, but then I… I had to start scoring it for the little orchestra, because I didn’t want to get behind. And it was a big job, so that, sometimes after, err, after I’d got the… had to catch the post at six o’clock. So, that was the, their rehearsal piano. And then, err, in the evening, I’d try and do a little bit about the scoring, you know, with, with the orchestra. And, if I felt like it, I’d try and think of the next piece. But it was really uncanny, sometimes, I found. I couldn’t quite believe how, how the tunes arrived, you know?

I remember on one occasion, I… I thought, “Well, I’d better start working on where, err, Aladdin has, kind of,” I’ve forgotten what it was, but it’s just, [sings tune]. It was just a little piano. I don’t often work at the piano. I don’t often get my themes at the piano. I just had to play this rhythm, and then I gradually got the tune. And then, suddenly, another tune arrived. And then, I got it down, and then another tune arrived. I could almost weep, you know? It… I couldn’t believe it. It wasn’t necessarily to do with, it didn’t necessarily… I didn’t care whether it fit, it was a good tune. And, um, it… it was like that all the time. But I, I couldn’t stop, you see? And apart from anything else, I had an orchestra and that was getting broadcast. And then, right in the middle of it, they decided that, um, they wanted some broadcast from me whilst the, the staff orchestras of the BBC were on holiday. And I couldn’t turn it down because the players at the North were so reliant on this work I was getting for them. So, I’d got that to do, err, in the middle of it and, err, so it was hectic all the time. I still had to keep thinking of Aladdin, but basically it was that, um, getting the, getting the music off for them to rehearse. So, that…

Patricia Linton: That was the pressure, really, that they wanted it…

Ernest Tomlinson: That, yeah, but it, it… I knew that the pressure would build up for the orchestral parts because of the time it would take me to do them. So, I had to keep doing those, but they, they, um, the piano. In a sense, it’s the only piano music I’ve written. I was never good writing for the piano, because I was an organist, and that means you’ve got three hands – in fact, you’ve got your feet. And I was a good organist. And so, consequently, that’s what music is, usually. It’s… it’s two hands and the feet, isn’t it? I mean, you know, you listen to Chopin, you think, “He’s moving around with his left hand, he could do with another hand.” Music’s like that, really. Doing the Aladdin changed it because it had a brilliant pianist – forgotten his name – who, who played for the ballet. The répétiteurs of ballet and opera, they’re often very fine pianists. And he was, and, knowing that it was going to be played as a piano piece, long before it was ever heard for orchestra, I forgot my feet and was writing for the hands. And it’s, really, I realised afterwards, I was now, at last, writing for piano, because the… the feet weren’t there.

Patricia Linton: But you said earlier that you, err, you didn’t usually use the piano for your themes.

Ernest Tomlinson: No, I, I don’t.

Patricia Linton: So, what, what do you normally do?

Ernest Tomlinson: Well, I… well I just sing them, and write them down

The transcript of this podcast may have been lightly edited for ease of reading.