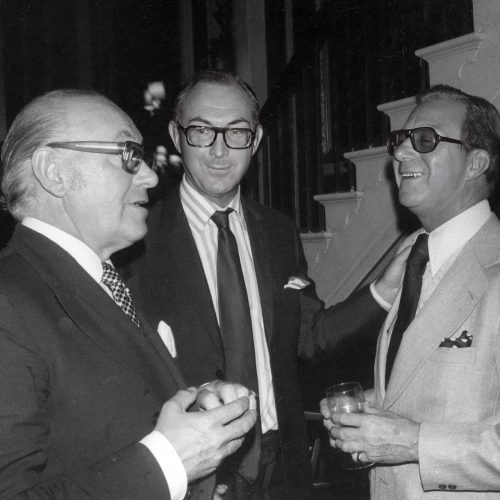

Clement Crisp

Critic and writer Clement Crisp gives a succinct and vivid summing up of the debt British ballet owes to Constant Lambert, not just as the conductor for the Vic-Wells and then the Sadler’s Wells Ballet, but as what Crisp calls their artistic conscience. He also speaks about Lambert’s own musical genius, both as a composer and a conductor, and his penchant for reviving unjustly overlooked music. The interview ends with the sad story of the ballet Tiresias and Lambert’s early death only weeks after its premiere. Clement Crisp is in conversation with Gerald Dowler, who also introduces the episode.

First published: July 26, 2023

Biography

Widely regarded as the doyen of British ballet criticism, Crisp was an imposing figure in the ballet world, both in person and in print, and was so for nearly half a century. His dazzling knowledge of dance (and other arts), authoritative style and occasional waspish barb made him a voice to be reckoned with. His passion for ballet began at the age of 12. He was educated at Bordeaux and Oxford Universities, and after spells in business and teaching, he became the ballet critic of the Spectator in 1966, followed in 1970 by several decades on the Financial Times. He was the Librarian and Archivist at The Royal Academy of Dance from 1968-1986, and Archivist until 2001. He wrote many books on ballet and its history and related arts, frequently co-authored with Mary Clarke. In 1992 he received the Royal Academy of Dance’s Queen Elizabeth II Coronation Award, and was also made a Knight of the Order of the Dannebrog, Denmark. He was awarded an OBE in 2005 for services to ballet.

Transcript

In conversation with Gerald Dowler

Gerald Dowler: This is Gerald Dowler for Voices of British Ballet, and I am sitting with Clement Crisp, who for half a century has been writing on dance, principally for the Financial Times. We are here to discuss the composer and conductor Constant Lambert, and his influence on British ballet.

Clement Crisp: My feelings about Lambert are of absolutely unrestrained respect. I know not one single bad thing about him, that he ever did, as an artist, as a conductor, as a musician, as a guide, as a conscience, he was absolutely sensational. And vital, central, to the emergence of the Vic-Wells Sadler’s Wells Ballet.

I was very angry with The Royal Ballet about 20 years ago. There was going to be an exhibition to celebrate 50 years of the company or some such thing and I was talking to somebody about it and I said “What are you going to do about Lambert?”, and he said, “Nothing”. “Oh yes you bloody are!” He was crucial to the establishing of the Vic-Wells Ballet, to the development of the ballet, to much more than just being in the pit. He guided people, he guided [Frederick] Ashton, of course he guided [Ninette] de Valois, essentially, he was, in some ways, as much the artistic conscience of the troupe as de Valois was. She needed Lambert, she needed Lambert’s wisdom and flair.

Gerald Dowler: Your earliest memory of Constant Lambert?

Clement Crisp: Well, the earliest memory, of course, is him conducting during the War. I can never hear La Calinda from Delius’ opera, Koanga, without being transported back to the Princes’ Theatre in 1943, because Lambert carried on what [Sergei] Diaghilev had initiated, which was orchestral interludes. If you look at the orchestral interludes that Diaghilev got from his orchestras, and his eminently distinguished conductors, they were fascinating. There was old music, there was new music, there was lost, forgotten things from Russian operas. All of this. Lambert took it over. Week after week, La Calinda would come up, but also, Philippe Gaubert, I don’t know if anyone even knows now who Philippe Gaubert is, but Lambert started playing him, he started playing little bits of composers whom he sought to foster and show, and educate us with. This was absolutely remarkable.

There is a vast repertoire of music that is almost completely forgotten and Lambert, who had a slightly Francophile, slightly Russophile taste, produced scores – conducting music – and if you look at the list of all the stuff he conducted in concerts, you will see how extraordinarily intelligent, how far ranging, and how, in a funny way, out of the current fashion, his choices were, but he was the most wonderful advocate for them. [William] Boyce, unknown had he not done something about him, [Frederick] Delius, and most especially [Emmanuel] Chabrier, whom he adored, and whose music he conducted divinely well, and [Franz] Liszt, of course, who was one of his favourite composers.

The extraordinary thing is, he did not like [Igor] Stravinsky. He did not like Stravinsky, he did not understand Stravinsky. I think he occasionally conducted Stravinsky, but by and large, it was not his bag. He had certain strictures also about the Second Viennese School, and in a way, he was proudly British in the way he made his music, even The Rio Grande, but Rio Grande, if you listen to it, you hear that it has got so much in it, so many extraordinary things. Parts of it are Chabrier, parts of it are pure Harlem, and some of it is, you know, South American. It is a wonderful score, and his other music that I recall now, one hears it so rarely, bloody BBC wouldn’t like to play it if you asked them.

A genius, he was a genius, you know, and the awful thing is, it’s unappreciated, but if you listen to those scores, even his arrangements, which was arranging Liszt, arranging Chabrier, arranging this, that and the other, he did it with such elegance, with such… without, shall we say, destroying the actual essential nature of the music that he was chopping and changing around. But you see, again, also, he was multi-talented. If you want to know what the wonderful sequence of words, and music that is Façade, of Edith Sitwell, you have to hear the recordings, in which Sitwell and Lambert are the narrators. No one has narrated it better than Lambert. There is one which begins, ‘“You should see me dance the polka” said Mr Wagg like a bear,’ and then the words, ‘Tra la la la la, tra la la-,’ I can’t say them, even at ordinary speed. Lambert does them at a prestissimo, they are clear, they are bright, they are absolutely exact. The fact he could do that, the fact that people like the Sitwells admired him. Osbert Sitwell writes very well about Lambert: very honestly, very generously, very admiringly. He presented himself to them and they found it irresistible, this very good-looking, rather heavily featured young man with a precocious intelligence and also, a real talent.

Gerald Dowler: Do you think that Lambert had any limitations?

Clement Crisp: Yes. Drink was one. Alcoholism. My friend, Elizabeth Frank, who had been a friend of his, Betty Frank, who was called [Elizabeth] Souvorova when she danced with one of the Ballet Russes troupes [Wassily de Basil]. Betty said, ‘Oh, Constant once said to me, ‘I know when I have had too much, when the pas de trois in Swan Lake turns to a pas de six!’ And also, we all forget that his whole life was spent with pain. He had various operations, each more painful than the last, he’d had something terribly wrong with one of his legs. He had a limp, of course, he usually walked with a cane. But, despite everything, he devoted his life, probably too much of his life, to the ballet, during the late 30s and the 40s.

His performances were sensational. That first night, when you first heard those first notes of The Sleeping Beauty [sings], you know. Ahh! Marvellous! Of course, he was a genius, you see, I think his genius may have been dissipated from doing too many things, in a funny way, what we may have lost in him from music, we gained from him, because of his devotion to the ballet.

The best thing I ever heard said about him was, I was talking to Dame Ninette de Valois, and she said to me, you know, ‘I used to pray,’ this was just the beginning of the War, ‘I used to pray, “Please God, don’t let anything happen to Constant.”’ She, of course, met him when he came to Diaghilev in 19-, what? ’25, ’26, for the Romeo and Juliet, and he was then a youthful prodigy, younger than she, and he wasn’t going to have his score mauled by Diaghilev, no, he was going to stick up for his rights. There was a certain arrogance about him, of course, and a wonderful, youthful self-confidence, but it showed a certain integrity about what he was doing, and certainly his sophistication.

Lambert knew, he sensed what was good and what was not good, and he knew what it was, because he had inbuilt good taste, if you like. I remember Alicia Markova saying to me, you know, when she was with the Vic-Wells Ballet in 1932, ’33, ’34, she said, ‘Well I can remember an evening when we all went into Constant’s flat, which was above a restaurant, and there was beat up upright piano’. He was playing through music to Alicia, and to Dame Ninette, talking about what they could do with it. His sense of what a ballet could use, was very, very, very acute. Markova said, you know, it was truly remarkable, because he would say, ‘Well this won’t, that won’t work,’ and so would go on, and this was one of the things that de Valois relied upon. Also, he did not hang around. If you listen to his recordings, and there are a lot of them, they are very good, there is a wonderful rhythmic shape. There’s a wonderful rhythmic energy in the music, none of that terrible dragging out of tempo ‘while I show you my arabesque.’ No. Get on with it! He wasn’t going to have music destroyed by foolish dancers.

His private life was confused, shall we say. One has also to accept the fact that from 19, what? ’37, ’38? I can never remember which, when he became [Margot] Fonteyn’s lover, this was also, in a curious way, the making of Fonteyn’s career, because, with Constant Lambert guiding you musically, he adored her musicality, which was staggering, but he also refined it, I think. The extraordinary speed, the vivacity, the energy, the clarity of everything she does. This is, in part, owed to Lambert.

The tragedy was, of course, that his last thing, which was Tiresias, really didn’t work at all. He was, by that time, it was alcoholism, and some form of diabetes I believe, as well, and the net result was that he wasn’t able to work, not really able to work much, and so not able to orchestrate. So the work was farmed out to various of his friends, I suppose in a funny way it was daring, it was about how this sex-changed man becomes a woman, becomes a man again, and beyond the fact that Fonteyn had quite an amusing solo in the middle movement, where Tiresias is a woman, John Field was Tiresias as a man, the whole thing was gloomy beyond belief, and should never have happened.

Gerald Dowler: Was his death, then, a shock?

Clement Crisp: It was a shock. And of course it did occasion an almighty storm. He had been made one of the trio of sort of associate directors of the The Royal Ballet, he and Fred Ashton and Dame Ninette, and Dickie [Richard] Buckle wrote a terrible review of Tiresias, which began, ‘Three blind mice’, suggesting that none of them really knew what was going on with that production, and a fortnight later, Lambert was dead. There then came a huge torrent of abuse from Osbert Sitwell, and this provoked an enormous scandal. David Webster, who was the wonderful general administrator of the Opera House and a great man, contrived to sort of calm the waters, as he so often did, but Lambert went out in a burst of sort of anger, and reproaches. Not essentially to him, but to the whole idea of how The Royal Ballet was being run with its triumvirate, which was most unfortunate. Everyone else gets terribly mealy mouthed about it, the fact remains that the work should never have hit the stage.

The important thing was that he established the Company, The Royal Ballet, as a truly musical company. And if the dancers were musical, it was not just because of how de Valois wanted them taught and trained, it was how Lambert encouraged, in a sense guided.

Three people made the Royal Ballet, de Valois, Lambert, and Ashton. God could not have been kinder to us.

The transcript of this podcast may have been lightly edited for ease of reading.