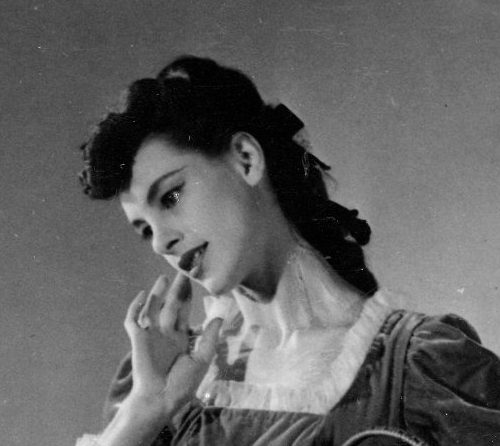

Antoinette Sibley

Antoinette Sibley talks with Alastair Macaulay. Her wonderful mix of enthusiasm, appreciation and practicality typify the glorious mercurial talent that has beguiled a generation of dancers and public alike. Sibley talks about her early aspirations, working with Frederick Ashton and her career-defining partnership with Anthony Dowell.

First published: March 22, 2025

Biography

Antoinette Sibley was born in Bromley, Kent, in 1939. She trained at the Arts Educational School in Chiswick before joining the Sadler’s Wells Ballet School in 1949 and The Royal Ballet in 1956. In 1959 she was coached by Tamara Karsavina, the great Russian Ballerina from the Imperial Russian Ballet and Serge Diaghilev’s Ballet Russes. Later that year she danced Odette/Odile in Swan Lake. In 1960, she became a principal dancer and in 1961 danced Princess Aurora in The Sleeping Beauty. 1964 saw a pivotal moment in her career: the creation of the role of Titania in Frederick Ashton’s The Dream, alongside Anthony Dowell’s Oberon. This was the start of one of the great partnerships in the history of The Royal Ballet, indeed of ballet, and one which lasted for nearly a quarter of a century.

Her professional stage career ran from the late 1950s until her late forties in 1988, with a few years of retirement in the early 1980s. During her career with The Royal Ballet, Sibley danced many principal roles in the classical and in the dramatic repertoires. She created major roles for Frederick Ashton, Kenneth MacMillan, Michael Corder and other choreographers. She danced with Mikhail Baryshnikov in the Hollywood film The Turning Point (1978). As President of the Royal Academy of Dance from 1991 to 2012 and as a coach at The Royal Ballet, her involvement in British ballet continued into the 21st century.

She was appointed CBE for services to dance in 1973, and DBE in 1996.

Transcript

In conversation with Alastair Macaulay

Antoinette Sibley: Because I was a classical ballerina – I looked a classical ballerina, the way I did the steps was a classical ballerina, and Margot [Fonteyn] certainly was a classical ballerina, but I didn’t want to be a copybook of Margot Fonteyn. I admired her hugely, but it wasn’t how I felt the music or how I-, I’m golden, I’m a golden haired girl, I’m not dark and ballerina like that. You know, black hair and white skin, and all that, I’m not. I’m golden and more luscious. And she was perfect, and I didn’t, I didn’t want to be perfect, or see myself as perfect. I rather liked undulating a bit and just getting there in time. And it’s not to say anything against her, because I thought she was absolutely miraculous, but I didn’t want to be like it. Which is why I was so, so lucky to have [Frederick] Ashton create The Dream for me, and for Kenneth [MacMillan] to create Manon for me. Nothing could have been more different from Margot in those two ballets.

Alastair Macaulay: Can we talk about another choreographer who was important to you early on, and that’s Bournonville. I was just seeing the Bournonville Festival in Copenhagen when I first met you, and you said, ‘Oh, for my generation, the Napoli Divertissements with Erik Bruhn mattered so much’.

Antoinette Sibley: Well, we were all in love with Erik Bruhn, every single one of us. I’ve never known all, I mean, what were there? Four of us, me, Merle [Park], Georgina [Parkinson] and Lynn [Seymour], and we were all in love with him. I mean, everyone was in love with Erik Bruhn. You couldn’t, we’d be, ‘Oh,’ like this, we couldn’t even do the steps properly, because we were just, sort of, looking at him. He’s so gorgeous, and he’s so adorable, and I remember, I mean, I’d go and watch things in the wings so that I could stand next to him, and I’d be standing next to him, and I wasn’t seeing anything on the stage. I was just standing next to him. He was just one of those people. Well, Warren Beatty. It was the perfect male personified. You just, ‘Ah,’ you couldn’t breathe, you just couldn’t breathe. You couldn’t be yourself, you couldn’t ask sensible questions, you know.

Alastair Macaulay: Yes, but you had to get on and do a variation. Was he a good teacher at that?

Antoinette Sibley: Oh, he was amazing, and of course, but no, he got up and showed us exactly what he wanted, and exactly how it should be done, and he was very enthusiastic, of course. He was teaching us first-hand Bournonville, and it was wonderful, the Napoli, that we did. A couple of us then were lucky enough to then learn the pas de deux that he did with Nadia, you know.

Alastair Macaulay: The Flower Festival?

Antoinette Sibley: The Flower Festival at Genzano, so we were able to go on and do that. I remember doing it, I think with him at one point.

Alastair Macaulay: There was a step that Fred [Ashton] loved you doing, and I don’t know what the step was.

Antoinette Sibley: Oh, I do, I do.

Alastair Macaulay: But you just said he put it into Dorabella from your Napoli.

Antoinette Sibley: I do. It came from my Napoli solo. I know exactly what it was, I’ll show you. It was absolutely wonderful, a wonderful step, and it’s from my Napoli solo. So there, and then round, right round, right to the back ‘day-um’ and then pas de bourrée, and that-, you jump into that. You jump into that, and then that’s all round the floor, and luscious like that, and then pas de bourrée.

Alastair Macaulay: I should say for the record that Antoinette is showing-, going from tendu front, leaning forward and then doing a rond de jambe à terre, with her whole upper body opening with a backbend too.

Antoinette Sibley: A full plié on this leg, and so ‘day-um’ and then a pas de bourrée to bring you up onto balance again, and then body ride over and…. Then you had a jump like that, and a jump, jump, jump.

The whole step was one I’ve just shown you, like three things, but he just used this one ‘day-um’, and she does it all-, that’s absolutely…. He loved that step. Loved it, mmm….

Alastair Macaulay: You said somewhere, not to me, I think, ‘At that point, I wasn’t Fred’[Ashton]s favourite”, and I would, did anything to try and win his attention, but he seemed to be more interested in the others,’ and your breakthrough role, which you killed yourself to win his attention for, was the Giselle peasant pas de deux. Can you talk through this?

Antoinette Sibley: No, you’re absolutely right. For some reason, and whether it was because I was with Michael Somes at that point, and he didn’t like that, you know, I mean, Michael had been married to Deirdre, Deirdre had died, so I mean, it was nothing to do with me taking, but I was then Michael Somes’ next girl, so to speak, and this was before we were married, clearly, and I thought maybe it was because of that, that he thought I was either trying to step into somebody’s shoes, or trying to put myself forward in advance of where I should have been going with Michael Somes, I don’t know what it was, but anyway, I was of the impression that I wasn’t in his favour, and he, he was, he made it quite obvious in a way. I mean, you know, I mean, I wasn’t one of the people he used, so it was quite simple. In a way, it was alright, because Johnny Cranko had given me such a good start, and um, Kenneth [MacMillan] used me all the time, and, but Fred himself, he just wasn’t very fond of me.

And I got this chance, it was the Giselle peasant pas de deux, and they’d just put, erm, the new-, a new bit in the solo, you know, it was quite boring. It was ‘ya-ta-ti-ta, ya-ta,’ it was quite, sort of, boring, but then they suddenly put, like a rond de jambe, and a bit more oomph to it, and all I know is, erm, I can remember, I can remember right now that on the night we were doing it, I was doing it with Brian Shaw, who was first cast, so I was having this rehearsal with him on stage, just him and me, because he was showing me where, because I’d never done it, and I was put on at short notice, so exactly where we went for every step. Um, and um, and he kept saying, ‘Look, come on, we can’t go on anymore. I’m absolutely exhausted, this is all you’ve got to do, you’re doing it fine’, and I said, ‘Yes, but it’s this, um, solo’. Der-er, dudyum, der-er, dudyum, ya-ta-ta-ta-di-di-di-di-ya-ta-ta-ta, and so I was practising this blimming thing on and on, and Brian said, ‘Look, I’m going away now, I can’t cope with this anymore. You can go on practising that step, I’m going now. I will see you at the right minute before we go on, alright?’ So I went, ‘Fine,’. Anyway, all I can tell you is it brought the house down. My solo stopped the show. Margot [Fonteyn] was furious.

Alastair Macaulay: I think that was the first Margot [Fonteyn]-[Rudolf] Nureyev Giselle that you did it at, of course.

Antoinette Sibley: Was it? Wow.

Alastair Macaulay: Something historical at that.

Antoinette Sibley: It was quite an important, certainly I think Margot [Fonteyn] and Rudolf [Nureyev] were on, I mean, and it stopped the performance, so nobody else was best pleased, but I was, and I think Fred [Ashton] was, because it was his solo, and I think that’s what, um, and I think he saw what I could do with his things, and everything changed from then on.

Alastair Macaulay: Ah, ah.

Antoinette Sibley: Mm, that was it. That was the turning point. So it was good I worked so hard on it.

Alastair Macaulay: So we come to Fred, and we come to this famous Dream 50 years ago, and he summons you in, and you don’t even know what lovers you’re going to be, apparently.

Antoinette Sibley: No, we’re down as lovers.

Alastair Macaulay: You’re just doing a pas de deux.

Antoinette Sibley: Well, you see, it’s on the noticeboard, ‘lovers’ and it was [Antoinette] Sibley, [Anthony] Dowell, [Merle] Park, Bennett. So we went, um, up, and we did the rehearsal, and he was seen to be taking an awful lot of notice of Anthony and I, and in the end, they were, like, doing it behind us, and we thought that was a bit odd, but he still didn’t tell us. I mean, nobody seemed to tell us, ‘But you are Titania and Oberon.’

Alastair Macaulay: Now, but I want to ask you about the pas de deux, because you said when it began with a pas de deux, he came in and said, ‘I dreamt of a fountain last night,’ and you spent the whole day trying to be a fountain.

Antoinette Sibley: Yes, because he had seen this dream, so he knew it could happen, and although we said, ‘Well, it couldn’t,’ and Anthony was braver than me in the end, because Anthony said, ‘Well, you know, I could do it, but I would have to cut her leg off, that’s the only thing,’ and he said it dead seriously like this, like he does and he said, ‘Well, I’m going to leave you. I’m going to leave you. I’m going down now. I’m going down to have a cup of coffee and a cigarette. I can’t cope with this anymore. When I come back, I want to see my fountain,’ and we had to go under a leg, and come up the other way, but we’re a…

Alastair Macaulay: So just that image when he folds you in two, you go through and then turn.

Antoinette Sibley: And you turn under, and you turn under, turn round, and come under, and you come up.

Alastair Macaulay: And up again into…

Antoinette Sibley: It looks quite simple, but it took us all that time, and when of course, the minute he went out the room we sat down on the floor, we’d better get on with it, he’ll be in, in a minute, what are we going to do?’ and then it just sort of happened.

You know, I mean, no other person had said, ‘Be a fountain,’ or something. They’d say jeté pas de bourrée or glissade, or they’d show us, you see. Kenneth [MacMillan] would show you the step, because Kenneth could still do the steps, so with Manon, he did my solo better than I did. I mean, he was just wonderful in my solo. [John] Cranko could show you the steps, but Fred didn’t do a step at all. He was always smoking, would just get off his chair, and sort of go, well, sort of like this with his arms, but nothing happened. You had to keep doing something until he saw that it was right. Then go, ‘Yes, yes, yes, now do that but with that other one bit that you did before,’ and so you had, you know, it was like, sort of, cutting out something and sticking it together.

Alastair Macaulay: Would he do with you what he did with so many dancers, which was to say, ‘Oh, but you should have seen [Anna] Pavlova, you should have seen [Lydia] Lopokova,’ and tell you about dancers, and ..

Antoinette Sibley: Oh, well, Anna Pavlova was always his, idol. I mean, Anna Pavlova was what he wanted us all to be.

Alastair Macaulay: And is it true that Ashton gave you eye exercises to do?

Antoinette Sibley: Yes, absolutely.

Alastair Macaulay: Do you remember what they were?

Antoinette Sibley: Well, I mean, he just said that nobody uses their eyes anymore, and he said, ‘The thing you noticed about Anna Pavlova were her eyes. Her eyes were absolutely,’ she had big, black eyes anyway, and this white, white face, and they were very prominent, and black hair shrouded round it. So it, sort of, pinpointed the eyes, but she used them so that she wouldn’t just be, like, dead, like that, you know, and doing something, she would use them. And from out front, if somebody is using their eyes, that’s why they sometimes look so dead nowadays. People aren’t looking at something, or seeing something out front. It’s like you’ve got a curtain down in front of you, and you’re just doing it in a room, or something. So this is something that he made us think about, to use the eyes.

Alastair Macaulay: Well, the next two major creations are pretty different. The Awakening pas de deux [from The Sleeping Beauty], that’s one of them in ’68, and the other was Dorabella [in Enigma Variations].

Antoinette Sibley: Dorabella.

Alastair Macaulay: What is it about Dorabella that straightaway makes you look melty like that?

Antoinette Sibley: Oh. It’s just one of my favourite roles. That solo is one of my favourite things ever. I just loved it, and Ashton loved me doing it. It was a really lovely solo. Wonderful. I just think, um, how lucky I was to be in that period of time that I was there, what with Anthony [Dowell], and what with [Frederick] Ashton, and, um, [Michael] Somes there.

Alastair Macaulay: It’s [Frederick] Ashton who creates the [Antoinette] Sibley [Anthony] Dowell partnership, which is so felicitous. You’ve got the same line, the same musicality.

Antoinette Sibley: The thing was, he was much younger than me. He wasn’t of my generation, so we didn’t talk to these younger people. They were like students, you know, we didn’t know them. They’d come in, they’d be at the back of the room somewhere, very shy, and Anthony [Dowell] very shy. Not even, the eyes weren’t raised up, it was like this, you know. I mean, he hardly looked at you, you know, and, um, no, so I wouldn’t have known him really, at all. I just wouldn’t have known him.

The first thing I suppose that happens, if one does it logically, is working together on The Dream, we just had the same timing. We felt the music the same way. People all hear music slightly differently, but somehow or other, he and I were in tune with each other the way a step was done. I suppose because our builds are similar. We’re very, um, classical and straight, but we heard the music the same way, which apparently is very unusual. I didn’t know it was. And so therefore when we did something, we were completely being natural in ourselves, we weren’t trying to do it with each other, that’s how we did it. So it wasn’t ever a problem, like sometimes when you dance with somebody you go, ‘Oh no, do your arm down here,’ or, ‘Could you do that, because I can’t quite do the same,’ if you are wanting to, but with us, it automatically happened. When I did my arms, his were echoing on the same-, just one level below me, presumably, exactly the same. You know, it was, um, it was extraordinary.

And I’d worked with so many people up to then. I’d worked with Michael Somes, doing my first Swan Lake with him, and I’d worked with David Blair, I’d worked with wonderful people, but somehow, when I got with Anthony [Dowell], it was, I think, hearing the music the same, because it propelled us at the same time. So it was like I was only doing it for myself, but he was doing it for himself, and it was the same. It was just together. It was, um, really extraordinary. Sometimes I’ve watched some of these videos, and you go, ‘Oh,’ I mean, it’s extraordinary.

Alastair Macaulay: We haven’t talked enough about épaulement.

Antoinette Sibley: Épaulement.

Alastair Macaulay: But Fred is the ultimate épaulement person, and he’s also, his middle word as David Wall used to say is ‘bend’, he’s always saying bend, bend, every which way. Were you a natural bender? Or did you have to do much more than was convenient when it came to Fred?

Antoinette Sibley: I thought I was a natural bender, because I’ve got a very long back, so when I do bend, I can go quite a long way. So I’d never had a problem with bends until I came to Mr Ashton, and he would poke you, literally poke you. ‘Bend more, bend more,’ just poke me, and there’s this film where he’s, um, rehearsing Anthony [Dowell] and I, I think it’s for Thaïs, and it’s on a film, and then you see us do the whole performance for him, and he’s sitting there with his cigarette and all this, but he just with his crooked finger, he keeps poking me. ‘You’re just not bending,’ and you are bending, and you don’t think you could ever bend anymore, you’ll break in half, and you can’t breathe when you’re doing it, but you had to. It was that extra couple of inches he wanted, and I must say, it made such a difference. And it’s awfully uncomfortable, and to bourrée, you know, in an uncomfortable position, it’s just uncomfortable but he loves that. Loves all that. Loved it.

The transcript of this podcast may have been lightly edited for ease of reading.