By Voices of British Ballet

Marius Petipa (1822-1910) was born in Marseilles into a theatrical family. He was performing publicly at the age of nine. When he was 16 he was the premier danseur in Nantes. He studied under August Vestris in Paris, where he also danced. From 1843-1847 he worked in Spain, where he produced five ballets, before going to the Imperial Theatre in St Petersburg in 1847. He was premier danseur there under Jules Perrot before becoming ballet master himself in 1871, a post he held until 1903, when he was ousted by a new director of the Theatre. Petipa remained in Russia, albeit as a discontented soul, until his death in 1910. He created no less than 54 ballets in St Petersburg, as well as reviving many old productions and creating dances for operas. Of his 54 ballets, two – The Sleeping Beauty (1890), and Acts I and III of Swan Lake (1895) – all with scores by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, remain to this day the core of the classical repertory, and for many represent the pinnacle of that tradition. A third Tchaikovsky ballet – The Nutcracker (1892) – was also meant to have choreography by Petipa, but because of his illness at the time it was entrusted to another ballet master, Lev Ivanov (1834–1901). It was, in fact, Ivanov who choreographed Acts II and IV of Swan Lake alongside Petipa in 1895.

In his own training Petipa combined elements of both French and Italian traditions. From this heritage he did much not only to create the Russian school from which his great ballets flowed, but also to form the basis on which Serge Diaghilev and the Ballets Russes developed their own approach. Diaghilev’s dancers had all been trained in the schooling set up by Petipa, and the new ballets of Mikhail Fokine and his successors certainly relied on what Petipa had bequeathed them, even if at times in reaction to it. Petipa thus forms an essential link in the chain from the re-birth of ballet in the 20th century to the French and Italian schools of the 19th century and earlier.

Petipa’s own choreographic career really began with his Pharaoh’s Daughter of 1862. Other notable early works include Don Quixote (1869), La Bayadère (1876) and Raymonda (1898). In his ballets he lifted the whole choreographic atmosphere and development by having far less mime than had been the norm and many more steps. There would be important dances for the corps de ballet and brilliant variations for the principal dancers with at least one grand pas de deux.

At the start of his choreographic career, Petipa gave his chief attention to the grace and beauty of line and poise, only rarely giving combinations involving high technique. In the latter part of the 19th century, however, there was an influx of Italian ballerinas and new male dancers into Russia. These included figures such as Carlotta Brianza (1867-1930), Virginia Zucchi (1847-1930), Pierina Legnani (1863-1923) and Enrico Cecchetti (1850-1928). Together with improvements in technique in Russia itself, Petipa and the Imperial Ballet then went on to reach new expressive heights, blending French grace with Italian fire and brilliance.

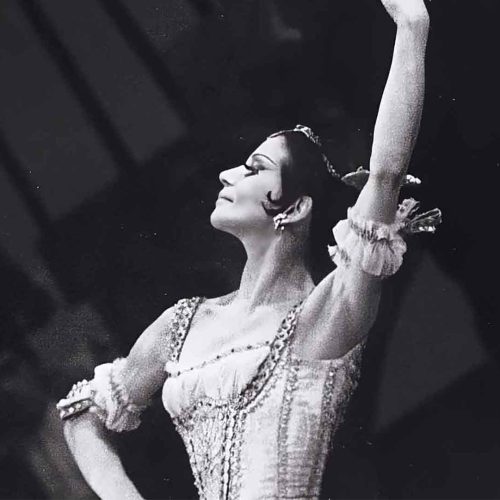

All these qualities came to fruition in the three great Tchaikovsky ballets, nowhere more symbolically than in Brianza’s creation of the role of Princess Aurora in The Sleeping Beauty in 1890. Princess Aurora is widely accepted as being a seminal achievement of classical ballet, if not its highest point. In it the ballerina has to find a whole gamut of qualities, including graciousness, formality, radiance, poise, dramatic breadth and depth, and mature perfection. Her dancing has to be endowed with nobility, perfect placement, clarity and continuity, as well as dramatic breadth and depth, a complete melding of which is achieved only rarely and by the best.

Over and above the purely balletic aspects of the three great collaborations between Petipa, Ivanov and Tchaikovsky, we should also note the remarkable way that Petipa – as ballet master – insisted almost to the last detail on what was required from the composer. Perhaps even more remarkable was the way Tchaikovsky obliged. Petipa found it difficult at times to adapt to the composer’s novel arrangements. He demanded that tempi be altered, cuts made and additions inserted. Tchaikovsky dutifully altered, cut and inserted, to produce the balletic and musical masterpieces we know today.

The dividing line between a Romantic ballet and a classical one is often slender. The mood and feeling of the Romantic ballets can be woven together with the form and line, and with the symmetry and order, of the classical approach. Petipa integrated the complex narratives and the emotional drama, along with the shifting between reality and fantasy, which are the hallmarks of romantic ballet, with the brilliance and elegance of the classical style. In his own way he also developed ballet beyond both trends of the past. His own approach involved large casts, and elaborate sets and extravagant costumes, along with increased virtuosity. He introduced pas de deux and exotic divertissements connected only tangentially to any plot, along with highly charged mime and gesture, all enclosed in settings of splendour and magnificence. These traits are triumphantly apparent in the three great Tchaikovsky ballets, in ways seen neither before nor since, which explains why, despite huge changes in history, taste and attitude since the 1890s, these three ballets continue to hold their pre-eminent place in the balletic canon.