By Nigel Simeone, author and musicologist

Pineapple Poll was a ray of sunlight at the start of the 1950s. It is entirely in the spirit of Diaghilev – a fusion of dance, music and design.

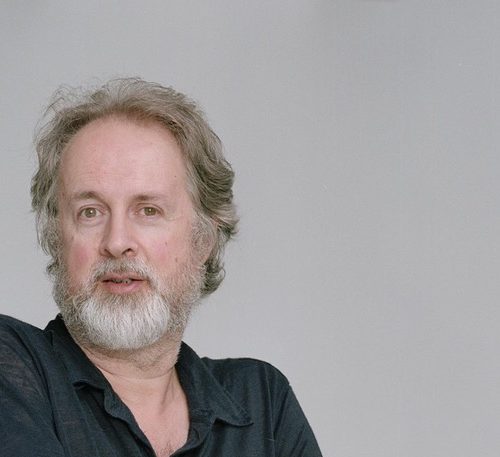

CHARLES MACKERRAS (b. Schenectady, New York, 17 November 1925; d. London, 14 July 2010), Australian conductor

Charles Mackerras had a distinguished career as an operatic and orchestral conductor, serving as music director of English National Opera (1970–77) and Welsh National Opera (1987–92) as well having a long association with San Francisco Opera, conducting regularly at the Metropolitan Opera, New York and the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden. His orchestral appointments included principal conductor of the BBC Concert Orchestra (1954–6), chief conductor of the Sydney Symphony Orchestra (1982–5), principal guest conductor of the Philharmonia Orchestra (2002–10) and conductor laureate of the Scottish Chamber Orchestra (1995–2010). He was knighted in the 1979, made a Companion of Honour in 2003 and was the first recipient of the Queen’s Medal for Music in 2005. His musical interests were wide-ranging: an outstanding advocate of Janáček’s music, he was largely responsible for establishing Janáček’s operas in the British repertoire. His Mozart performances from the 1960s incorporated elements of historically-informed performance practice that caused controversy at the time. His interest in Handel led to the first recording of the Music for the Royal Fireworks using Handel’s original forces, and an influential recording of Messiah including vocal decorations and musical variants. Mackerras was an extremely versatile opera conductor, at home in a vast repertoire ranging from Gluck to Britten (with whom he worked closely in the 1950s). His aim was always to present operas as the composer had intended (producing his own editions of Handel, Mozart and Janáček, among others), but also had the most acute sense of theatre. He was a Gilbert and Sullivan enthusiast from childhood and conducted their operettas throughout his career, as well as drawing on them for Pineapple Poll. As an orchestral conductor, he often worked with period-instrument groups, particularly the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment, and brought historically-informed playing styles to his work with the Scottish Chamber Orchestra. His outstanding performances of mainstream orchestral works (Beethoven, Brahms, Dvořák, Elgar and others) made for a particularly happy association with the Philharmonia Orchestra in the last decade of his career.

Mackerras collaborated on two comic ballets with the South African choreographer John Cranko: Pineapple Poll (1951) based on music by Arthur Sullivan, and The Lady and the Fool (1954) based on lesser-known works by Giuseppe Verdi.

The origins of Mackerras’s interest in Pineapple Poll went back to his childhood in Sydney. His family knew the Gilbert and Sullivan operas well and some of his formative musical experiences came through productions put on by his school, St. Aloysius’ College, starting with Trial by Jury in 1933 and HMS Pinafore in 1934. Mackerras’s first solo role came in 1935 when he sang Kate in The Pirates of Penzance and year later he was Leila in Iolanthe. His biggest role came on 14 October 1937, a few weeks before his twelfth birthday, when he sang Ko-Ko in the St. Aloysius’ production of The Mikado. This was even reviewed in the Sydney Morning Herald (15 October 1937), which singled ‘the interpretation of Ko-Ko, the Lord High Executioner, by Charles Mackerras [who] kept the audience chuckling.’ Seven decades later, in 2009, Mackerras conducted Patience at what turned out to be his last Prom. In the spoken introduction on BBC Radio 3 he recalled these early Gilbert and Sullivan experiences: ‘I was brought up with it, you know. Everyone in our family knew Gilbert and Sullivan by heart. All the operas, all the dialogue, and all the jokes. … And when I was a kid I acted in the Gilbert and Sullivan operas. … I still love it very much’ (BBC Radio 3, 11 August 2009).

Mackerras got to know Gilbert and Sullivan even better during his teens, above all during a long season given by J.C. Williamson at the Theatre Royal in Sydney, in 1941–2. He turned sixteen on 17 November 1941 and played the oboe in the orchestra for a season that included The Gondoliers, The Pirates of Penzance and Trial by Jury, The Yeomen of the Guard, The Sorcerer, Iolanthe, Princess Ida, HMS Pinafore and Cox and Box, Ruddigore, and Patience. After being quietly dropped from the schedule because of Australia’s declaration of war on Japan in December 1941, The Mikado was reinstated ‘by universal demand’, opening on 17 January 1942 ‘in merry defiance of the Japanese menace’ (according to the Sydney Morning Herald). Mackerras went on to play in several more seasons.

This extended exposure to the Savoy operas gave Mackerras an idea that was to bear fruit a decade later. He also worked as a rehearsal pianist for the Kirsova ballet company in Sydney, where he discovered Manuel Rosenthal’s arrangements of Offenbach for Gaîté parisienne and the Rossini-Respighi Boutique fantasque. He later wrote that ‘the idea of transforming the music of the Gilbert and Sullivan operas into a ballet score occurred to me while I was playing in the orchestra for a Gilbert and Sullivan season in Australia. How wonderful it would be, I thought, to arrange these eminently danceable tunes into a sort of symphonic synthesis and score them for full orchestra.’ Richard Merewether – a horn player in the Theatre Royal pit and a great friend of Mackerras – said he wished Sullivan had given the horns more to do, and started inventing extra horn parts. Mackerras undoubtedly had this in mind when arranging Pineapple Poll which includes some wonderfully flamboyant horn writing.

Mackerras sailed for London in the spring of 1947 and it was to become his permanent home. He first worked as an oboist by the Sadler’s Wells Orchestra where he fell for the young principal clarinet, Judith Wilkins. They were married on 22 August 1947 and set off a few weeks later for Prague, where Mackerras had a British Council scholarship to study conducting with Václav Talich. On returning to London he was taken on as an Assistant Conductor at Sadler’s Wells. The first opera he conducted there was Die Fledermaus, on 20 October 1948 and it was soon followed by many more.

With the expiry of Sullivan’s copyright in 1950, Mackerras set to work on the ballet. His enthusiasm for Sullivan and his tremendous skill as an orchestrator – acquired through detailed study of scores, and from making transcriptions of recordings to perform works that were unavailable in wartime Australia – made him the ideal person for the job. The copyright having lapsed, the D’Oyly Carte company could not make any sustainable objections to the reuse of the music, and Mackerras later said that Bridget D’Oyly Carte ‘accepted the situation with as much grace as possible.’

As well as its imaginative use of a full-sized symphony orchestra (much larger than anything Sullivan had available in the original operas), the success of Pineapple Poll also lies in the ingenuity with which Mackerras combines music from different operas to create momentum from the unexpected juxtapositions of tunes. The alternation between the opening music of Mikado and Trial by Jury right at the start is a demonstration of this, the ideas flowing gleefully into one another as if they’d always meant to do so. As to why some tunes were chosen in preference to others, Mackerras’s sister Joan remembered that ‘Charlie decided to use very little of Pinafore since its story was so close to Pineapple Poll [both were based on Gilbert’s The Bumboat Woman’s Story, No. 81 of the Bab Ballads] and he kept the opening of the Yeomen of the Guard Overture in reserve, so to speak, for the ending of the whole ballet. He also wanted something like a Can-Can, so he chose “Sing hey to you” from Patience as the closest thing to that.’ As for the details of the orchestration itself, there are amusing allusions to more serious fare than Gilbert and Sullivan: at the start of Poll’s Solo in Scene 2, the Invocation from Iolanthe is given Wagnerian orchestral colours – a cor anglais solo straight out of Tristan und Isolde and a trumpet playing the Iolanthe idea, scored to resemble the ‘Sword’ motif in the Ring.

In the notes for his 1960 recording, Mackerras listed the original sources as follows:

SCENE 1:

- Opening Dance: The Mikado, Trial by Jury, Patience, The Gondoliers.

- Poll’s Dance and Pas de deux: The Gondoliers, Princess Ida, Patience.

- Belaye’s Solo: Cox and Box, Patience.

- Pas de trois: The Mikado, The Pirates of Penzance, Ruddigore.

- Finale: Patience, The Pirates of Penzance, Ruddigore, Iolanthe.

SCENE 2:

- Poll’s Solo: Iolanthe

- Jasper’s Solo: Iolanthe, Princess Ida.

SCENE 3:

- Belaye’s Solo and Sailor’s Drill: Princess Ida, The Gondoliers, Ruddigore.

- Poll’s Solo: Trial by Jury, Iolanthe, Patience, Princess Ida.

- Entry of Belaye with Blanche as bride: The Yeomen of the Guard, Trial by Jury, Iolanthe.

- Reconciliation: Ruddigore.

- Finale: The Mikado, Trial by Jury, HMS Pinafore, Patience, Princess Ida, The Pirates of Penzance, Overture di Ballo, The Yeomen of the Guard.

The premiere of Pineapple Poll took place at Sadler’s Wells Theatre on 13 March 1951, in a programme of four Cranko ballets (the others were Beauty and the Beast, Sea Change and Pastorale). With Cranko’s ebullient choreography and sets by Osbert Lancaster, it was an immediate hit with audiences and the press. In June 1951, Mackerras and the Sadler’s Wells Orchestra recorded the complete ballet and Desmond Shawe-Taylor in the Observer (12 August 1951) welcomed it as ‘an English Boutique fantasque, an unexpectedly fortunate result of the recently expired copyright in Sullivan’s music. The intoxicating tunes have been brilliantly arranged and scored.’ Lionel Salter (Gramophone, October 1951) praised ‘an ingeniously-constructed new work in its own right, based on Sullivan’s themes but following neither his orchestration nor, always, his harmonic progressions – certainly not his dramatic sequence’. He particularly enjoyed the ‘brilliant finale, in which themes from (at least) three operas appear in swirling key-changes. It is indeed this apt and fertile invention which is the root of so much delight in this ballet.’

Building on this success, Mackerras and Cranko next collaborated on The Lady and the Fool, made for Sadler’s Wells Ballet and first performed at the New Theatre, Oxford, on 25 February 1954 and at Sadler’s Wells Theatre on 31 March 1954. The principal male roles (the clowns Moondog and Bootface) were danced by Kenneth Macmillan and Peter Wright, with La Capricciosa taken by Patricia Miller (a role later danced by Beryl Grey and Svetlana Beriosova). The original sets were by Richard Beer. Like Pineapple Poll, this was a comic ballet though the music was drawn not from light-hearted operetta but from some of Verdi’s lesser-known works, several of which were completely unknown at the time. As well as selecting the music, the orchestration and arrangements are also all Mackerras’s own, with results that are often extremely colourful, operatic music reimagined for a large symphony orchestra. In the notes for his 1955 recording, Mackerras listed the original sources:

No. 1 Prelude: Alzira.

No. 2 Adagio: Alzira.

No. 3 Divertissement: I vespri siciliani.

No. 4 Tarantella: Il finto Stanislao, Giovanna d’Arco, Aroldo, I vespri siciliani, I due Foscari.

No. 5 Commedia: Il finto Stanislao, Aroldo.

No. 5a Allegro vivace: Ernani.

No. 6 Grande adage: I due Foscari, Ernani, I masnadieri, Macbeth.

No. 7 Scene and entrée: Atilla, Ernani, I vespri siciliani, Alzira.

No. 8 Solo by Signor Midas: Il finto Stanislao, Jérusalem.

No. 8a Entrée and Solo for the love-sick Prince of Arroganza: Ernani, I lombardi.

- Dance for the Débutantes: Il finto Stanislao, Don Carlos.

- Variation for Captain Adoncino: Il finto Stanislao, Oberto.

- Coda: Pas de cinq: Jérusalem, Atilla.

- Scene and Pas de deux: I vespri siciliani, Aroldo, I masnadieri.

- Finale: Ernani, I lombardi, I vespri siciliani, Aroldo, Luisa Miller, Jérusalem

- Adagio molto calmo: Jerusalem, Aroldo.

Critical reaction to The Lady and the Fool was at least as enthusiastic as it had been for Pineapple Poll. In Gramophone (October 1955) Andrew Porter described it as ‘probably John Cranko’s finest ballet to date’ and reviewing Mackerras’s own recording with the Philharmonia Orchestra (January 1956), Porter concluded by saying that ‘few “arranged by” ballet scores are so positively enjoyable in their own right as this one.’

Mackerras made three complete recordings of Pineapple Poll (1951, 1960, 1982) and one of The Lady and the Fool (1955). All have been reissued on CD. A DVD has been released of 1959 television broadcasts of both ballets using Cranko’s choreorgraphy and conducted by Mackerras.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

Mackerras, Charles: ‘Pineapple Poll’, disc notes for EMI CDM 566538-2

Mackerras, Charles: ‘The Lady and the Fool’, disc notes for Testament SBT 1326

Phelan, Nancy; with appendices by Charles Mackerras: Charles Mackerras: a musician’s musician (London: Gollancz, 1987).

Simeone, Nigel, and John Tyrrell (eds): Charles Mackerras (Woodbridge: Boydell, 2015).