By Anthony O’Hear, philosopher

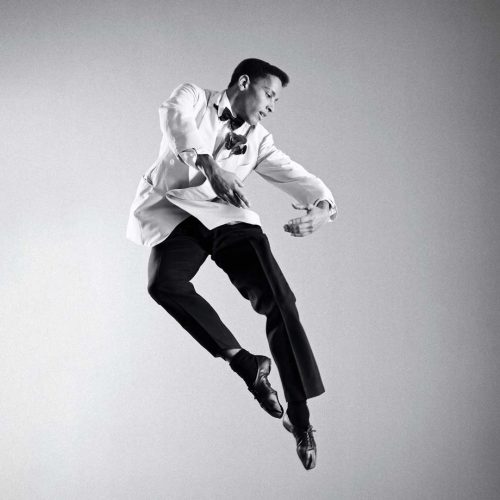

According to Virginia Woolf, ‘on or about December 1910 human character changed’. The event from 1910 she was referring to was the famous exhibition entitled ‘Manet and the Post-Impressionists’, organized by Roger Fry. This may be accurate as an account of subsequent literature and art in Britain. Certainly the Russian Ballet can be seen as contributing to the change of spirit Virginia Woolf is referring to.

According to Virginia Woolf, ‘on or about December 1910 human character changed’. The event from 1910 she was referring to was the famous exhibition entitled Manet and the Post-Impressionists, organized by Roger Fry. It certainly had a shattering effect on Edwardian public artistic taste, at least on advanced public taste, focusing as it did on Cezanne, Gauguin and van Gogh. In 1910 London was also about to be hit by Diaghilev and the Russian Ballet, while the avant-garde of the art world were drinking in the innovations of Matisse, Picasso and the other cubists. In poetry Ezra Pound was beginning to experiment with W.B.Yeats. The modernist movement was in full swing in all the arts. And then there was the first world war, whose effect completed the destruction of the old certainties, moral, political, social and philosophical, as well as giving further impetus to the artistic revolution already underway.

Things were never again to be as they had been as recently as 1901 when Elgar wrote his magnificent Cockaigne overture, the main theme of which occurred to him (in his own words) ‘one dark day in the Guildhall, looking at the memorials of the city’s great past and knowing well the history of its unending charity, I seemed to hear far away in the dim roof a theme, an echo of some noble melody…’ By the time that Virginia Woolf wrote about 1910 (it was actually 1924), it must have seemed that the noble melody Elgar heard in the Guildhall at the turn of the century would never again be played, at least not in artistic circles. According to standard histories of art in the twentieth century, cubism and neo-classicism were succeeded by surrealism, which in turn gave way to a type of primitivism, then abstractionism, then pop art, and so on, as one international movement followed another, each dominating for a time in galleries and sale rooms all over the world. And similar stories are told about music, architecture and even literature, about how modern, revolutionary styles and approaches pushed out the old and the familiar.

But, as far as Britain was concerned, the standard histories of art are just wrong, especially about the period from 1920-1960. It was true that the sort of noble confidence of an Elgar was never to be regained; however, many artists, and in the opinion of many, many of the best artists did try to recapture a quintessentially English or British feel for nature, for Britain itself, and for a traditional aesthetic, quite different from what was happening in Paris, or later, in New York.

Take, for example, the sculptor Henry Moore, a figure famous all over the world for his monumental bronzes which can be found in just about every major city. Moore, a Yorkshireman by birth, who was very influenced by native sculptures from Africa and South America began his career with abstract and surrealist work. But as he developed, he started producing the marble and bronze mother and child, and warrior figures with which he made his name. The mother and child complexes, semi-abstract in style, can also be seen as reflecting the Pennine landscapes of Moore’s childhood; the reflecting of motherhood and landscape, the earth being the mother and the mother the earth, being a theme far more ancient in history and native feeling than the pre-occupations of the artistic avant-garde of Moore’s time. And, in considering Moore, we should also mention his drawings, particularly those of the sleepers in the underground, people seeking refuge from the bombing in the Second World War, and immortalized by Moore as monumental beings beneath the earth, who will one day awaken and rise – as indeed Britain did after the six years of war in 1945.

Graham Sutherland was a painter more or less contemporary with Moore, and almost approaching Moore in stature and reputation. Again, in Sutherland, we see the influence of surrealism, but once again transformed into mesmerizing, sometimes menacing, studies of strange landscapes, particularly of Wales, hills and dense tubular plants and growths transformed into ever more complex organisms. Sutherland himself wrote evocatively of his way of working in the Pembrokeshire countryside: ‘I noticed thorn bushes and the structure of thorns as they pierced the air. I made some drawings and as I made them a curious change developed. As the thorns rearranged themselves they became, whilst still retaining their own pricking, space encompassing life, something else – a kind of stand-in, for a Crucifixion and a crucified head.’

Like Moore, Sutherland drew on and explored the overlaps between the human and the natural. In this quest they were both reflecting an old pre-occupation rooted in ancient dances and myths from the British Isles. I think that we cannot underestimate the effect that two world wars had on the artists of the twenties, thirties, forties and fifties, and the sense many of them had that they were involved in a struggle to keep alive an ancient landscape, an ancient tradition and an ancient way of living, often against the new and horrible mechanization of war, but not only of war. They had a deep feeling for the country, its roots and its feel, a feel which was being encroached upon by the invasion of the machine and of suburbia.

William Blake, and the artists who followed him in the nineteenth century, such as Samuel Palmer, were an influence on many of them, Palmer with his mysterious and gnarled Kentish landscapes and Blake with his visionary writing and thinking. Take, for example, Blake’s most famous poem, Jerusalem – something everyone knows, but hardly any understand.

‘Did those feet in ancient time/ Walk upon England’s mountain green?’ WHOSE feet? Blake tells us, but few listen: the holy Lamb of God; and he speaks of Jerusalem being ‘builded here/ Among these dark Satanic mills…’ Blake is here drawing on ancient myth, that Joseph of Arimethea came here, to Glastonbury, after burying Christ, and Christ himself came here before his baptism in the Jordan. All wholly fanciful, but what was not fanciful was the feeling many artists of the mid twentieth century had for the English and Welsh landscapes and of the sacred meanings buried within. And not only visual artists; the great, neglected artist and poet David Jones, a man permanently traumatized by the First World War, wrote unforgettably not only about the war (In Parenthesis) but also about the meaning and life and history buried in the land beneath our feet (Anathemata, The Sleeping Lord).

David Bomberg and Paul Nash also fought in the 1914-8 war. Nash producing one of the greatest and most evocative of first world war paintings (We are making a new world 1918), and an equally striking one of the second, a graveyard of shot down German planes (Totes Meer 1940-1). But in between the wars, and up to his death in 1945, Nash produced a huge series of ever more strange and uncanny landscapes and paintings of natural objects, at one surreal and intensely real, always suggesting a life beyond the life we know, but always rooted in a particular place and a particular object. Bomberg is particularly interesting for our theme, because before the 1914 war he painted some very striking cubist like paintings, in which in avant-garde mode human bodies are given cylindrical form. But the war’s mechanization repelled him, and in the 1920s he turned to landscape and portraiture, first in a fairly traditional topographical style, but then of an ever-more incandescent visionary nature, bringing our what he called the spirit in the mass, wonderful evocations of scenes in Spain, Cornwall and Cyprus. But in 1944 he also produced an absolutely iconic image of St Paul’s Cathedral standing, untouched and proud, in the midst of the surrounding buildings blitzed, burning and ruined.

We can, perhaps, call all the artists so far mentioned neo-romantic, in that they were all attempting in one way or another to produce recognizably romantic themes in a style which owed something to the artistic trends of their time – hence neo-romantic. But if we take romanticism more literally, as referring to the type of work produced by Samuel Palmer in the first half of the nineteenth century – highly romantic landscapes, at once highly detailed and dense, but visionary at the same time, then three Johns, Piper, Minton and Craxton may be see as the quintessential neo-romantics of the twentieth century. Piper produced a great number of highly wrought paintings and drawings of English scenes, of churches, great houses and of ruins or semi-ruins at times deep in woods, often in stormy or dramatic weather. He was in fact commissioned do many of these scenes in the Second World War in case their subjects were destroyed by bombing. Minton and Craxton both began their artistic careers in the Second World War, and during this period both produced some highly romantic work, making the English countryside into a kind of arcadia in which figures danced and dreamed, far from the sound of bombs or guns. It is interesting to note that both Piper and Craxton went on to design for ballets after the war, one of Piper’s being for Ninette de Valois’ ballet Job, the designs based on the work of William Blake.

Even from this brief account of the English neo-romantic artists it should be obvious that their aspirations were high and their approach serious, features which the wars obviously heightened. In both the World Wars there was also a conscious effort by the authorities to involve artists in the war itself, to depict it and perhaps to boost morale (though this did not stop some of the artists we have been considering from depicting its futility as well). But particularly in the Second World War the art produced seemed to reflect not just the seriousness of the war, but also its significance and the desperate situation into which Britain was thrown. High mindedness of this sort was prominent in the work of T.S. Eliot, whose writing was almost from the start infused with a religious spirit and also, increasingly, with a deep affection for England, or, more accurately, for the old England of his Anglican forebears. His poetry too was uncompromisingly serous, like the work of Moore and Sutherland, modernistic in style and form, even while expressing far more traditional attitudes and aspirations. A good example of Eliot’s uncompromising approach may be found in the apparently simple two stanza fourth section of Little Gidding from The Four Quartets.

The section opens with ‘The dove descending’, breaking the air with ‘flame of incandescent terror’. This is both a bomb and the Holy Spirit, and we are to be redeemed, if we have hope, by fire (purgatory, the bomb) from fire (hell); in the second stanza Eliot writes of the intolerable shirt of flame, which is a reference to the shirt of Nessus, given unwittingly to Herakles by Deianeira, his wife, which will consume him by fire, but given to him (and us) by Love – as we might hope to be purged by the burning love God gives us. Even in the 1940s few could have written like that, but Eliot’s late work, which despite appearance is not simple at all, quickly became canonical for the time, and subsequently.

It said something about the time, that it was written and admired at the time, much like Myra Hess playing Bach and Beethoven (German composers) in the otherwise empty National Gallery through the blitz. Nor should we forget the efforts of the Committee for Education in Music and the Arts (CEMA) to bring the highest art to the general public. Under the leadership of John Maynard Keynes (who was married to a Russian ballerina, Lydia Lopokova), CEMA mutated in 1946 to become the nationally funded and administered Arts Council. This was the first time in Britain that there had been a system of public subsidy for the arts.

In its early days the Arts Council was uncompromisingly elitist in the proper sense, its motto being ‘the best for the most’; and those running it, starting with Kenneth Clark, the great writer on art, had no qualms about what the best was. Moore, Sutherland, Piper in the visual arts, in dance Sadler’s Wells Ballet, in modern music Britten and Tippett (who like many of the figures we have been considering combined a modern style with traditional aesthetic aims, eschewing the doctrinaire modernism fashionable where the doctrines of Schoenberg held sway). There was also, on national radio, the Third Programme, which subsisted on a diet of serious classical music, serious drama and poetry from the ancient Greeks to the present day, and talks and discussions of uncompromising authority, without any interruption or humour from chummy ‘presenters’. Its stratospheric ambition (and achievement in the early days) prompted the Minister of Education for the day, a former communist called Ellen Wilkinson, to say that it was her ambition to create a ‘third programme society’.

It could not happen, and it didn’t. The optimism of post-war reconstruction represented by the early Arts Council and Third Programme gave way in the 1950s to a very different mood. Along with increasingly rebellious and anti-authoritarian political and social attitudes among the young, sometimes for quite understandable reasons to do with the bomb and the collapse of the British Empire, neo-romanticism and all that it meant fell out of fashion. Poor John Minton committed suicide in 1957, his mood hardly helped by the failure of his later exhibitions and the attitude of his students in the Royal College of Art who were clamouring for abstraction and pop art.

The mood of the late 1950s was best summed up by John Osborne’s play Look Back in Anger produced in 1956. It was indeed a landmark, the phrase ‘angry young men’ being coined to reflect its meaning. But what was its meaning? The hero Jimmy Porter is certainly angry – with his long-suffering wife, with his father in law, with England, with the Empire, and much else besides; but no one really knows why he is angry or what he actually wants. But the play is realistic, sordid in its setting and definitely un-aspirational. Its cynical tone became the tone of time artistically. In 1961 Philip Larkin wrote a poem in which the speaker (a fashionable jet-setting university professor) speaks of the remembrance day parade in London as ‘solemn-sinister/ Wreath-rubbish in Whitehall’. Larkin may have been sending the professor up – one cannot be sure – but what the professor thinks in the poem was what many academic luminaries of the time thought, and doubtless still do think. And when Larkin also told us that ‘the myth kitty’ is now empty, both the sneer and the sentiment are in his own voice. That being the predominant opinion among the intelligentsia, there would be little hope for the flourishing or even survival of a trend like the neo-romanticism we have been considering, for it depends, explicitly or implicitly, on the viability of myth, or at least of the spirit within which myths can touch us and live.

As far as the visual arts went in the late 1950s and 1960s, a short infatuation with American abstraction was followed by a much longer infatuation with equally American pop art. In 1957, the pop artist Richard Hamilton pronounced that art now had to be ‘popular, transient, expendable, low-cost, mass-produced, young, witty, sexy and glamorous’, and indeed it was (and maybe still is). Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein were not British, of course, but much of the fashionable art produced in Britain in the 1960 is in the shadow of New York. Anthony Caro, meanwhile, Henry Moore’s one time assistant, gave up working in stone altogether, in order to produce bright constructions in painted metal, quite cheerful, but quite empty. He also announced that anything could be sculpture (or was it anything could be sculpture?). Rather to his chagrin some of his students took him literally – not just to mean that sculpture could be made any sort of stuff, but that anything could be sculpture, walking across a field, writing a jokey slogan, drinking gin in a gallery, an unmade bed. Caro, whom I got to know a bit, always used to say to me that my interpretations of sculpture were ‘just literary’. However, towards the end of his life he produced semi-abstract sculptures in metal, of figures from Homer’s Iliad and also his own variations on the pediments from the temple of Zeus at Olympia. I found these works impressive and moving, not least because they showed that Larkin et al notwithstanding, the myth kitty is, even to-day, not completely empty. The mid twentieth century neo-romanticism is past, but we can still return to the myths that have nourished our civilization from its beginnings.