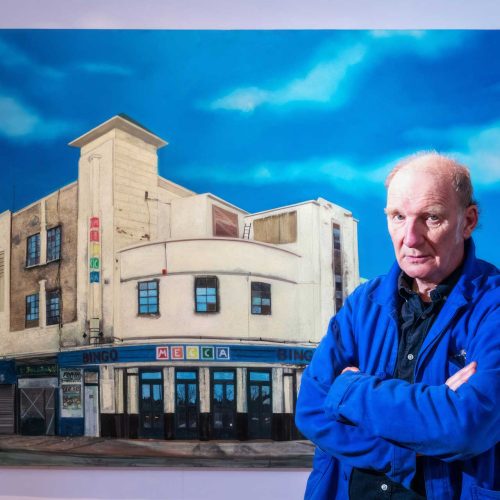

Jock McFadyen

The artist Jock McFadyen was a true performer in this interview! Picture us in the Sitters Gallery at the Royal Academy of Art – people walking through and noise everywhere. The acoustics were impossible, and our technician, Rodrigo, is on his knees, holding the microphone as close to Jock as possible – he didn’t move a muscle for an hour! Jock was completely unperturbed and the perfect gentleman. Patricia Linton, founder and director of Voices of British Ballet, talks to Jock about his work on the designs for Kenneth MacMillan’s The Judas Tree. We hear about Jock’s own rebellious days as a student and about how, as a complete newcomer to ballet, he became involved in The Judas Tree. He quickly realised that he preferred narrative to abstract ballet – Goya to Mondrian, as he puts it – and about how he saw MacMillan as the Francis Bacon of ballet. Disclaiming any knowledge of a deeper religious meaning to the ballet, Jock speaks of the difficulty of representing a rape in ballet, and also of MacMillan’s conflicted attitude to authority, with his worries about Princess Margaret being offended by the explicitness of Jock’s sets.

First published: July 8, 2025

Biography

Jock McFadyen was born in Glasgow in 1950. His family moved to Stoke-on-Trent when he was 15. He went to art school before being thrown out when he was 17 but eventually went to the Chelsea School of Art in 1973. After graduating with a BA in 1976 and an MA in 1977, he quickly established a reputation for his gritty pictures of working class life in the inner cities. Deborah MacMillan saw some of his work in an exhibition in Cork Street, as a result of which McFadyen was engaged to work on the designs of her husband, Kenneth MacMillan’s last ballet, The Judas Tree in 1991. Partly as a result of his work on this set, representing London’s Docklands, McFadyen began to work on evocative urban and later rural landscapes. McFadyen was elected to the RA in 2012, and his work is in many major public galleries both in Britain and overseas.

Transcript

in conversation with Patricia Linton

Jock McFadyen: Actually, I was thrown out of art school when I was 17. Because of my imagination. It was 1968; it was the year of the Hornsey riots and the Guildford sit-ins. It was the ‘60s. Drugs and sex and all that. Getting thrown out was a way of alerting me to the fact that I did have an imaginative life, I suppose, because that’s what was being objected to. This was Foundation College. You know, you do a foundation course before you go to do a degree. So I had five years between my foundation course and my degree course at Chelsea School of Art in 1973. And that was because I was chucked out.

Patricia Linton: You were chucked out because you were objectionable or your art was?

Jock McFadyen: Hopefully both

Patricia Linton: Did you think at that point that you were going to get back into college and get on with art?

Jock McFadyen: Well, I had done a sufficient amount of work to realise that I didn’t want to work for a living.

Patricia Linton: All right.

Jock McFadyen: Well, I think that’s true of Kenneth MacMillan, too. Isn’t that true? I mean, I think his real name is Billy Elliot. But, you know, I mean, there is this escape from the reality of everyday life and working and pensions and mortgages and all that stuff, too.

Patricia Linton: We’re going to have to skip a few years, then we’re going to talk about The Judas Tree. I think it was Deborah MacMillan, actually, who first saw your work, it wasn’t Kenneth. And she came back and told him to go and see… you had an exhibition in Cork Street?

Jock McFadyen: Yeah, I used to show, the dealer in Cork Street called the William Jackson Gallery.

There was an answering machine message from Kenneth MacMillan. The first person Kenneth introduced me to by chance, at our first meeting was Jeremy Isaacs, who I got on with very well. We did sort of prop up the bar a few times subsequently.

Patricia Linton: So. you had the telephone call. You went to the Opera House. Jeremy Isaacs, knowing him and being personable, as you say, did that help you to make the decision? Or had you already decided you were in?

Jock McFadyen: Oh, no. Susie, my wife wouldn’t let me not do it because she wanted to get comps to go to the ballet every night. She was pregnant at the time with our first child. We went to see the ballet every week because I could say, as a designer, to Monica Mason, who did get a bit cheesed off with us ringing up every week for comps, “Oh, I need to have a look at the stage again, because I’m working on my design.” We enjoyed it.

Patricia Linton: You hadn’t been to the ballet before that?

Jock McFadyen: Never. No. I just thought, it’s fantastically sexy.

Patricia Linton: Can you remember what you first saw? Your first realization of what it could be? Or who was dancing?

Jock McFadyen: Darcey Bussell, I think, in some popular hit – “white” ballet. I didn’t like avant garde ballets and minimalist sets. And I didn’t really like the athleticism of Sylvie Guillem, that kind of ballet. Nothing against her. But, you know, it seemed to me to be quite similar to abstraction and painting: Mondrian as opposed to Goya. You know, other art forms do define your own position in your own art. I think even if you’re completely ignorant about …you still recognize aspects and positions: formal formalism versus narrative, or a hard and soft romantic, classical, hard edge, painterly, warm. You know, there are positions in all of this. And I got my sea legs and decided to see some ballets, not others, out of curiosity. And I went to see Mayerling because of curiosity, imagining it was some sort of … that Judas Tree was a little ballet. But there were elements of one in the other, I thought. I did think that Kenneth MacMillan was a sort of Francis Bacon of choreography, but I wasn’t quite sure because I didn’t know about any other choreographers. But certainly with Judas Tree, I felt it was it was that kind of art. You know, it was dark and sexual and violent and nasty and cathartic. And, you know, all of those things were true about it.

Patricia Linton: But that’s the sort of criticism MacMillan constantly had levelled at him. Sort of, his treatment of women. Actually, Brian Elias, he said that because of the repeated resurrection of the female character, this made his motives more profound than just superficial violence. I wonder what you think about that. Did you see her as the Mary mother of God or Mary Magdalene?

Jock McFadyen: Well, I got the reference, of course. But. I thought the gang rape was pretty weird. I liked the counterpoint between the form of ballet, not contemporary dance, not some kind of minimalist mime or something, but ballet and a gangbang was an amazingly, powerful thing. But that’s just a technical observation. It’s a bit like saying, you know, you like the juxtaposition to Richard Hamilton still-life of the toilet roll next to the vase of flowers. It touched on being almost pornographic, but it seemed to me to be a bit like one of those forms, the literary form perhaps, which is bound by censorship. So everything has to be explained in a way which is secret.

So you can’t … if it was a movie, a gangrape would be people fucking actually wouldn’t it? You’d see it. You’d see every part of it if it was a [Quentin] Tarantino movie. Now what do we see in the ballet? We see people stepping over each other and being dragged underneath people’s legs which are apart. We see all of those gestures, which seem to me to be fantastically surreal because there were a bit like, you know, the [Luchino] Visconti movie, Death in Venice, which is very, very menacing the way the repetition of the the ha ha ha with the weeping Dirk Bogarde, isn’t it? This repetition and it becomes quite surreal. It’s like repeating a word which becomes abstract or look at your face in the mirror for too long after you’ve had too many drinks, you know, begins to, it begins to become abstract.

So I yeah I really enjoyed all that side of it.

Patricia Linton: What did Kenneth explain to you about the ballet? What did he say it was about before you started?

Jock McFadyen: He said that he always starts from a very abstract point of view and doesn’t really know what he’s doing and that he just had a few ideas like punctuation things. I think he wanted an object in the middle of the stage, which could be a tree: it ended up being a scaffold. But the painting that he wanted to model the costumes around anyway. Was this one…

Patricia Linton: Yes. Costa del Dogs

Jock McFadyen: …and there were there were problems, of course. Technical problems. High heels was the main one.

To go back to your previous question about the things that he and the ideas he had. There were mechanical ideas that he knew he wanted – the corps de ballet, he wanted all the boys in the ballet who are now all famous choreographers and stuff themselves because it was so long ago. But he wanted, he wanted a gang, he wanted the gang leader of Marlon Brando type, if you like. And the woman. So he had that, I think in mind. But there was a lot of talk subsequently about Tiananmen Square, which well, was not mentioned at the time.

Patricia Linton: He didn’t talk to you about that? As you say, there’s a lot of talk about him. This feeling of guilt and betrayal. Was very much on his mind. It probably was always on [Kenneth’s] mind. But they say that Tiananmen Square sort of it was 1989, I think, that pushed him…

Jock McFadyen: Yes, it was still fresh. But essentially, I think, whether it’s a personal, whether it’s a personal, confessional thing, because he jettisoned his working class roots, faked a letter to, you know. Dame, what was her name? Ninette De Valois…did the Billy Elliot thing. And maybe there’s guilt about that. Maybe there’s guilt about…

Patricia Linton: They say there’s guilt about his mother…

Jock McFadyen: There might be guilt about that.

Patricia Linton: .. that she was ill.

Jock McFadyen: There may be guilt about his sexuality. Yes, there might be. There certainly was a… – from the short time that I knew him and didn’t know him well – he was obviously conflicted about being an enfant terrible and also being a member of the authorities. And one of the arguments we had was about the graffiti because he was terrified of authority, I think, royal authority and also in opposition to it.

Patricia Linton: I mean, I presume you’re referring here to the “FUCK” on the back cloth that he wanted moved more into the wings.

Jock McFadyen: It was more, the argument was more like, “Jock McFadyen, I can see the word “cunt” from here. I don’t want Princess Margaret to see that.” So that’s more or less it. Of course, Princess Margaret was the Bohemian member of the Royal Family at the time, so I’m sure she wouldn’t … But no, I think there was that dilemma in him.

Patricia Linton: Pressure of the Opera House. You can’t get away from it when you’re in.

Jock McFadyen: It’s obviously a bloody closed shop and a difficult place to penetrate.

Patricia Linton: How aware were you of this gnostic gospels theme that Brian Elias had uncovered?

Jock McFadyen: Totally unaware

Patricia Linton: Totally unaware?

Jock McFadyen: Yes

Patricia Linton: Because there’s this whole, erm, “thing” of Jesus coming to earth as a woman, as a prostitute, and being used and then having to ask God for forgiveness to get back to heaven again, I’m putting this extremely badly …

Jock McFadyen: No but I can attach it to the ballet that we know.

Patricia Linton: …that would certainly work, but it was hidden in the way the Gnostic gospels themselves were hidden.

Jock McFadyen: Was that written about by Deborah Craine or any of those people who write about that?

Patricia Linton: Only Jann Parry, but eventually, only eventually, because she was the only critic, because it was hidden and you only had this quote from The Prophet and the programme and no names. There was no idea that there was Jesus or Peter or Mary because they weren’t referred to in the programme. They were in rehearsals but not in the programme. It was Jann Parry that came a little bit close to understanding. All the critics hated it, of course. And he telephoned her. She says this in her book.

Jock McFadyen: Did all the critics hate it?

Patricia Linton: Yes, on the whole.

Jock McFadyen: I remember good reviews. I think there might have been a feminist position on it, of course. But it’s interesting because I didn’t pick up on it because of my inferior education and lack of religious, no, I mean, I’m from a completely non religious family, Protestant working class Scottish family that never went to church once except for school or for weddings or something. But when I was making the case for ballet being a form which is done in code because it can’t be explicit, because it has to be within the confines of the form of ballet, I suppose, and also censorship. That’s what I meant, rather than a literary narrative or reference to the Gospels or to myth.

I actually meant to you, that in fact you couldn’t show people raping. You know, you couldn’t see someone ripping her clothes off. It was done in a convoluted, kind of coded way and that was in a formal way, very exciting because it enabled you to see the whole thing in that way, that this world of gesture and dance, which I was unfamiliar with.

The transcript of this podcast may have been lightly edited for ease of reading.